Letters Across the Diaspora

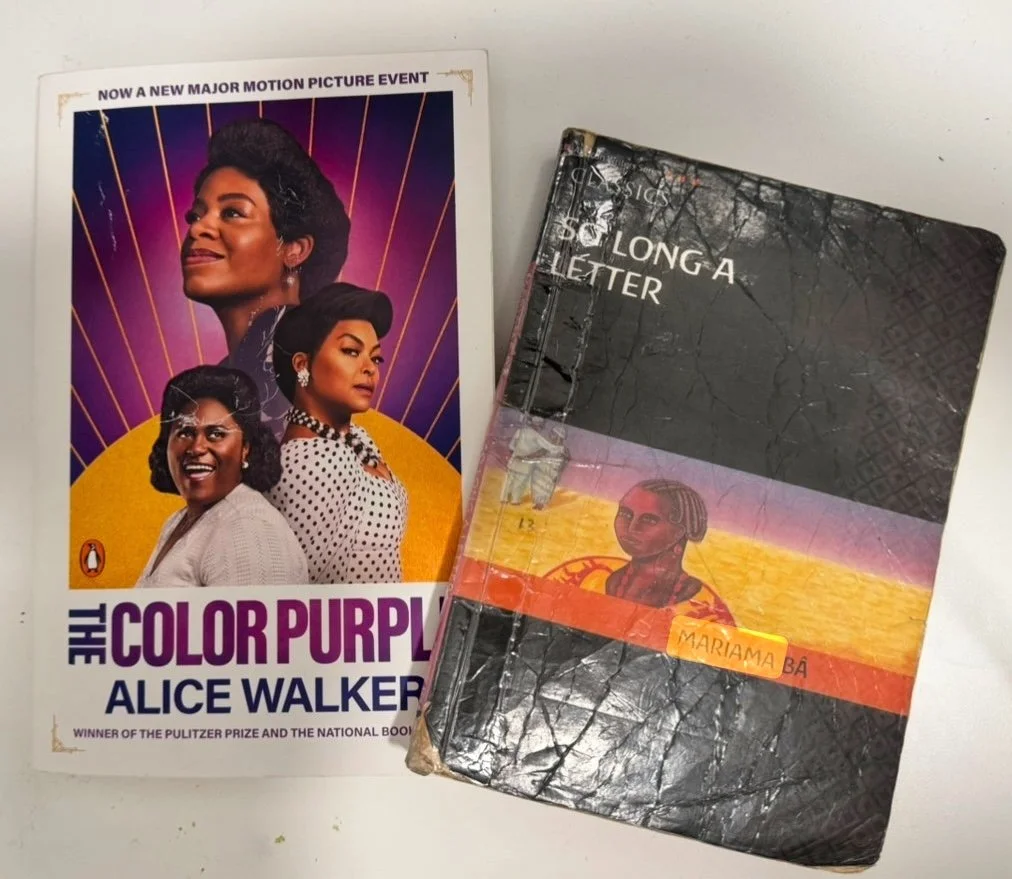

Reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and Mariama Bâ’s So Long a Letter felt like listening to a love song; or a prayer to God; of two women having a conversation across continents. One is from the American South, the other from Senegal, West Africa. Though set in vastly different worlds, both novels tell stories of women navigating pain, betrayal, and societal expectations, while discovering their voices and reclaiming their power in a man’s world.

I first read So Long a Letter in junior secondary school. Despite its brevity: about 88 pages. I’ve returned to it often, each time finding new layers of meaning.

In 2024, I watched The Color Purple on the big screen in Harlem, New York. The film left such a deep impression on me that I rushed home, eager to dive into the novel. I remembered buying the book from a local vendor on Harlem’s bustling 125th Street, near the Apollo Theater. As I turned its pages, I couldn’t help but notice striking similarities between Walker’s and Bâ’s writing styles. Both authors use letters as a storytelling tool, creating an intimate connection with the reader. Celie writes to God and later to her sister Nettie, something most of us do in our loneliest moments, while Ramatoulaye pours her heart into a letter to her dear friend Aissatou. This epistolary style feels personal, like sitting across from a friend, listening as they reveal their deepest fears, hopes, and dreams.

At the heart of both novels are women grappling with oppressive systems. Celie endures years of abuse, silenced by the men who control her life, until she finds the courage to fight back, supported by women like Shug Avery. Ramatoulaye faces the heartbreak of her husband’s betrayal when he takes a second wife; an act permitted by Senegalese culture but one that leaves her emotionally shattered. Her solace comes from the friendship and understanding she shares with Aissatou.

As I read The Color Purple, I found myself wondering: Could So Long a Letter have influenced Alice Walker? After all, Bâ’s novel was published earlier. Out of curiosity, I searched the internet, hoping to find a connection, an interview, an article, anything that might confirm my suspicion. But I was disappointed; I didn’t find any concrete evidence to support the idea. What I learned, however, is that at the heart of literature lies a universal language that resonates with people of all races, whether in Asia, Europe, or Africa. While the experiences of women in Senegal and America may seem different on the surface, they’re rooted in the same systems that try to silence, control, and define women.

In today’s world, where women’s rights continue to be challenged, these stories deserve a place on every bookshelf. They remind us of the struggles faced by Black women, disabled women, Christian women, Muslim women, atheist women, queer women, uneducated women, unemployed women, and even the powerful women who are often expected to bear it all in their silence.

Melvin Sharty is the co-author of "Talking Kapok Tree & Other Short Stories", and author of "A Gift for Failure (a novella). Melvin lives in Harlem, New York where he works for a non-profit. During his free time, he enjoys writing, visiting museums, or playing soccer.

The Art of James Baldwin and Chinua Achebe: A Reflection

During their first meeting at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 1980, James Baldwin had described Chinua Achebe’s writing as “a magnificent confirmation of the human experience,” while Achebe praised Baldwin as “a passionate, unflinching, and prophetic writer” who illuminated “the darkest corners of human existence with uncompromising honesty.”

When I think about art, I see it as both a mirror and a tool—on one side, reflecting the world as it is, while on the other, reimagining it as it could be. For Chinua Achebe, art represents “man’s constant effort to create for himself a different order of reality from that which is given to him.” For James Baldwin, art is an unrelenting pursuit, where the artist “must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.” Reading Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Achebe’s Arrow of God (1964), I was struck by Achebe’s provocative portrayal of art and Baldwin’s investigative depth—how they both understood the issues of their time and defiantly captured the essence of how art shapes and interrogates the human experience.

Art’s ability to interrogate human experience or our reality of being has often provided grounding for those, like myself, caught between worlds. As a nonimmigrant living and working in Harlem, New York City, I have frequently turned to Baldwin’s and Achebe’s works to reconcile my present and find help about writing my own memories of home. For many Africans who leave the continent in search of new beginnings, whether it’s education or job, loneliness and homesickness are like sides of the same coin that draw you on both ends. For me, reading and writing have offered me balance, and a space to tell my truth.

While reading Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), I noticed how he portrays truth as the cornerstone of an artist’s responsibility, a means of personal and societal liberation. As uncompromising and often painful, he viewed truth as “always necessary”. As he wrote, “It’s the artist’s duty to confront and reveal truth, no matter the cost.” Similarly, Achebe placed truth at the heart of his art, which if you read for instance Things Fall Apart (1958), you will notice how Achebe juxtaposed the Igbo traditional beliefs with Christianity without judgement. Truth, for Achebe, was not merely a moral compass by which to justify, but a lens through which to view reality.

When I arrived in Harlem in the winter of 2023, a local historian told me, “A half-truth is a whole lie,” a phrase which has ever since, pushed me to observe Harlem with strikingly familiarity—like Freetown, Accra, or Dakar, where the concrete street life, busty markets, and congested traffic, greet you with passion. Harlem welcomed me, much like Freetown, but I see vividly, a city embracing one of its heroes, in the food, the jazz, the blues, swag, in churches, and books. For Baldwin’s Harlem, preserving truth is a necessity, a calling to represent their heroes and preserve their truths. No wonderI caught myself engulfed in the writings of a man who had rested in power a century ago, and even in exile, Baldwin’s art remained deeply rooted in the struggles, triumphs, and histories of Harlem.

Baldwin left the United States for France in 1948 at the age of 24, escaping the suffocating weight of systemic racism. In The Fire Next Time (1963), he reflected on how Harlem remained with him even in exile, shaping his perspective and art.

Achebe, on the other hand, experienced political exile after the Biafran War, an event that deeply informed his later works, such as Anthills of the Savannah (1987). For both Baldwin and Achebe, exile became a platform for reflection and deep observation—a reconnection to their past. Baldwin needed to escape Harlem to tell its truth; Achebe carried his truth with him across continents. Through their works, both writers served as bridges between their homelands and the broader world.

Another reason I am drawn to Baldwin’s and Achebe’s works is their portrayal of male characters, reflecting the complexities of masculinity, identity, and societal expectations. As someone raised by a single mother, I experienced abandonment at a young age. My father, though a gifted artist, struggled to channel his love for art into love for his children. This tension often makes me question the balance between an artist’s devotion to their craft and their commitment outside of it.

In Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), he created a male character; Gabriel, who grappled with guilt and societal oppression. Similarly, in If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), Baldwin’s Fonny, a sculptor, fights for personal liberation in a world dominated by systemic racism.

Achebe’s male characters, like Baldwin’s, face similar struggles. For instance, Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart (1958) is driven by a fear of weakness and failure, shaped by his father’s perceived shortcomings and his inability to stop the emergence of a new religion that threatens to dismantle his world—forces that ultimately contribute to his downfall. Both authors demonstrate how societal forces—racism in Baldwin’s Harlem and colonialism in Achebe’s Nigeria—shape and often destroy their male characters.

Yet, if there is one theme I have continually drawn from their work, it is the persistent need to rewrite my own script—to seek my truth and embrace my responsibility as a writer.

Melvin Sharty is the co-author of "Talking Kapok Tree & Other Short Stories", and author of "A Gift for Failure (a novella). Melvin lives in Harlem, New York where he works for a non-profit. During his free time, he enjoys writing, visiting museums, or playing soccer.