ants on the wall

1.

you watch ants crawling on the wall. black teardrops in reverse. they move against the grey paint. ants being born from monuments erected in honour of your state of mind: half-eaten biscuits in yellow wrappers; week-old caramel candies on the floor, melted; sandwich tainted green by time; bowls with milk and cereal still inside; spilled sugar; spilled juice; empty packets of snacks whose names no longer have meaning to you. outside, in the living room, your mother’s prayers mingle with the prayers of emmanuel from church. they ask god to forgive whatever transgression has cursed your family, your father, your siblings, you. they ask god to drive away demons because depression, or when a daughter puts blade to her wrists, or loss of appetite, or financial struggles, or when a child talks back to their father, or infidelity, or when a father distances himself from a son, or anything along those lines, is merely a wrong name for evil spirits. they pray like this every evening, erupting like volcanoes. you watch ants crawling on the wall. you hate them, the ants, not the prayers because you are certain they will never work. how did it get so bad? you try to move, knock away the ants on the wall. you want to do something, anything, but your body is no longer your body. you are stuck in place.

2.

you watch ants crawling on the wall. black teardrops in reverse. they move against the grey paint, upwards. you watch your body from outside yourself. it lies motionless, paralyzed, uninterested in existence, on the naked bed. you watch yourself watch the ants on the wall. how did it get so bad? outside: prayers like lava march toward the stars. you count the ants. one two three four five six seven eight. is this the apocalypse of the self? beside you are mountains of dirty clothes. hills of dead socks. you see that white lace dress you wore to church that thursday a friend and a group of strangers tried to force demons out of you—stains still on the sides from when you fell and wept, mouth growing wider and wider, on those hallowed grounds. the piles of clothes and underwear and towels have been untouched and unwashed for so long they’ve grown eyes, blinking and staring at your motionless body on the bed. your mother enters the room. her movements, unsure. she parts the blinds; sunlight screams into your eyes. she sits by you, puts your head on her lap. she plays with your fingers. emmanuel has returned to his church. she sighs. she speaks. maybe she tells you to join her in prayers next time. her voice sounds like rain a million miles away. you hear a single drop, after a while: tell me what to do, she prays, what to do to make you better.

3.

you watch ants crawling on the wall. black teardrops in reverse. they move against the grey paint, upwards. week-old caramel candies on the floor, melted; bowls with milk and cereal still inside. the odour of a sandwich given to you by a lover about a week ago, a lover whose hands do not know how to make you better, but they try. you watch your body on your mother’s lap from outside yourself. moments ago, she was in the living room praying like volcanoes sending their innards to the heavens. demons leave my home, my family. now, she prays to you. tell me what to do, what to do to make you better. tell me what to do. tell me what to do. you’re suddenly grateful for the space between you and your tongue. what answer could you have willed the organ to give? tell me what to do, what to do to make you better. what answer—when you can’t even tell how it got so bad, why it got so bad. how do you begin to explain you are not sad, only empty? how do you begin to explain you do not believe your body is your body; your soul dances out of harmony with your flesh? how do you begin to explain you want to drop out of school, explain how nothing around you seems real, explain how everything feels like clouds drifting away? your mother’s voice staggers then stops. you watch ants crawling on the wall. tiny, spiked legs.

4.

no ants on the wall? no week-old caramel candies on the floor? no bowls with milk and cereal still inside? no mountains of dirty clothes, underwear, towels, eyes? the odour of a sandwich given to you by a lover about a week ago, is gone? change. time. how much time has passed since the ants on the wall? you think of time, the movement of it. in what second, on what day, week, do things unbecome themselves? change, you think of change. what to do to make you better?—the prayer of a mother, repeating, even as she walks away, fades away. was that yesterday? was that last year? you close your eyes. do we become better in jagged leaps, a sudden lurch? do we flow, like a stream, like light? where do ants go when no longer crawling on the wall?

5.

no ants on the wall. no week-old caramel candies on the floor. no bowls with milk and cereal still inside. no mountains of dirty clothes, underwear, towels, eyes. the odour of a sandwich given to you by a lover about a week ago, is gone. smells in your room: clean sheets, coconut, mother’s love. you return into your body, slowly, afraid of the fog and thoughts you will find inside. memories come in flashes; mother carried you to the bathroom; mother washed you, soap and sponge and water; mother cleaned the haunted landscape of your bedroom, laundry, filth on the floor, ants. mother. mother. mother. how can the littlest things return hope to us? mother. you get out of bed. the tiles, cold against your feet. this is your body. you find your mother in the kitchen, doing the dishes, humming a song. she is not perfect—the blind prayers, the endless talks of demons, the unlearning she needs to do, the etchings from her childhood deep in her bones—but she tries, in her own way. she turns around. tears drown her eyes when she sees you standing on the doorway like a ghost. you say nothing. you cry and tremble. she rushes to you, wiping her hands on her dress. arms outstretched. she smiles. she hugs you. this is your body. no ants on the wall. everything will be fine, your mother says, and for the first time in forever, you believe those words again. she holds you so tight. and you whisper, you pray, please, never let me go.

Victor Forna is a Sierra Leonean writer based in his country’s capital city Freetown. His short fiction and poetry have been published or are forthcoming in Fantasy Magazine, Lightspeed Magazine, Nightmare Magazine, and elsewhere. He is an alumnus of the 2022 AKO Caine Prize Writing Workshop. He tweets @vforna12.

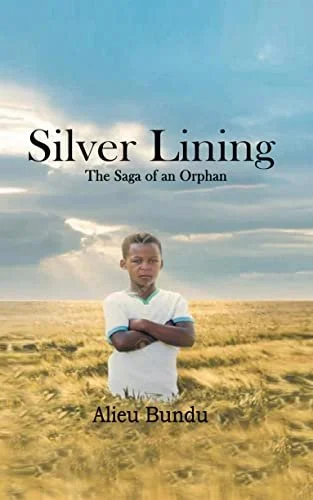

Alieu Bundu publishes novel, Silver Lining : The Saga of an Orphan

Sierra Leonean author Alieu Bundu has published his novel, Silver Lining : The Saga of an Orphan . He shared an excerpt with Poda-Poda Stories.

In war-torn Sierra Leone, an orphan is plunged into a tumultuous world of chaos, danger, deceit and abuse. Silver Lining is a story about family, love, loss, separation, war, friendship, faith, hope, courage and forgiveness.

***

“Have you done what I ordered you to do?” Aunt Mariatu asked as she placed the basket down. Her body was covered with a light sheen of sweat.

“No Aunty, but I…”

Aunt Mariatu shot Alimu a spiteful look that rendered him mute. He felt a sense of dread.

“What! You dared defy my authority, right? You wait, I go show you say are bad pass orbado!”

She grabbed a bucket of water that perched nearby and poured its content over Alimu.

He gasped, bounded onto his feet and looked at Aunt Mariatu with an open mouth and horror-stricken eyes.

“Yes, you merited that for being stubborn! Just wait, I’m going to beat the devil of stubbornness out of you!”

Aunt Mariatu dashed into the house and returned with a thick, long cane she called “Bamboo Bone”, which she started using on Alimu four days after his father returned.

“Now, lie down let me deal with you!” she roared, her eyes glowed of fierce anger.

Alimu didn’t move; he just stood like a pillar, looking at his aunt as an eruption of anger coursed through him.

His action flared up the overwhelming rage that was boiling in his aunt’s guts like a fire somebody had just thrown a five gallon of petrol at, because she raised the cane and started to hit him on different parts of his body. Searing pains stung Alimu on the parts of his body the cane landed like a hook; he covered his face with his hands to protect it and his eyes.

After unleashing Bamboo Bone for over twenty-five times, Aunt Mariatu stopped and said at the top of her voice in Krio, “Yes, are miss you! This is just one part of the punishment you will undergo! You want to grow wings in this house because I let you go to school! From now on, you will never go to that school again! Once I get into the house, I will take your uniforms and lock them in my room!”

“Aunty, please don’t stop me from going to school,” Alimu whined. His voice cracked.

“No way!” She grabbed Alimu’s backpack that was lying on the porch and dashed for the entrance door. Once she banged it behind her, Alimu, whose body felt as though it was swathed with acid, lowered his feet onto the floor as tears gushed out of his eyes. A while later, the door opened with a crash and Aunt Mariatu sauntered out. She was holding Alimu’s school uniforms and backpack.

“To show you that I was serious when I told you that I wouldn’t let you go to school again, I’m going to burn your uniforms and your school bag. If I keep them, you’ll hope that I will change my mind and send you to school again someday. But burning them means you will never go to school again,” Aunt Mariatu said, glowering.

Her words struck Alimu’s heart like a hammer. “Aunty, I beg you in God’s name, don’t do that!” His words were lined with grief like the cry of a woman whose beloved child was massacred by a car in front of her.

Aunt Mariatu didn’t pay heed to his words. She walked out of the porch and dropped the uniforms and the bag on the ground. Once they thudded on it, she poured kerosene on them and set them on fire. As flames of orange and blue meandered skywards as the fire consumed Alimu’s school bag and uniforms, he felt like a hostage who had just been informed that the person that was to pay his ransom had died in an accident.

You can get the book here: Silver Lining: The Saga of an Orphan

Alieu Bundu is a writer and a singer from Sierra Leone. He holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in French from Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. His stories have been published in Lolwe and Nice Story. He was the runner-up for April 2014 Africa Book Club Short Reads Competition, and he was also nominated for the 2016 Writivism Short Story Competition for his short story, Bintiya, now titled Miremba.

The Curse of Konsiloh

by Ebunoluwa Tengbe

“Konsiloh,” Abu whispered. He lowered his voice not because he was worried he would wake his parents but he could not dare say the name out loud. He and his siblings were seated a few meters away from the makeshift bedroom where their parents slept and that at dawn, would be rearranged to be the living room in the single room occupancy they called home.

The iron sheets which formed the walls of their home gobbled up the sun rays during the day and somehow never managed to excrete it by nighttime. This was partly the reason why the siblings now perspired as they listened to Abu’s story. They were also afraid; even though they had heard this story many times before. It was an old favorite that Abu told very well. It changed a little bit every time he told it. They knew each time he would forget some twists from previous versions and then add some new ones, but they didn’t mind at all. It was just a story. Well, most of it. And it was the parts that weren’t fictional that scared them most. Those parts never changed. Those parts were about Konsiloh.

Konsiloh’s parts came in the middle, usually after some tragic incident, a suspicious death, or some strange event had occurred.

Abu always started by describing Konsiloh’s clothes. The faded rust-coloured rapel he wore was sparsely marked with short white lines and visibly dark brown stains. Abu said he wasn’t sure, but it was rumoured that they were old blood stains that could never wash out, even if he tried, even though it was doubted that he did. He wore no sleeves and the marks that littered his body could easily be seen. They weren’t the scars of an accident-prone youth. They were careful incisions made during sacred and fearsome rituals that fueled his prowess. Around his neck and on his arms, wrists, and ankles were multiple strands of raffia threads, wound together, dipped in concoctions brewed from powerful and mystical herbs picked from the deepest parts of the bush.

His face was last. Abu described him as a man who kept a full beard, a sharp contrast to his bald head. His lips, like other men in the region, were dark and full, as was his nose which spread generously across his face. He could even have been described as handsome, if not for those eyes. Framed by bushy brows, his dark pupils pierced through a sea of redness and not from drinking poyo. His sling bag was never missing from his side and neither was his dog. The mongrel had a uniform jet-black fur that shone in the moonlight to match his master’s skin. No one knew the dog’s name; it really didn’t matter for what use would it have? Even his master’s, which was known, was rarely said out loud.

Konsiloh was a purist. Firm in his belief and incorruptible in his practice. This ensured no compromise to the potency of his power. His potions were guaranteed to work and his curses, irreversible.

“Konsiloh,” Abu repeated. “Stop!” Amie, the youngest, pleaded, fearful that the utterance of the name would somehow invoke the presence of the bearer. Satisfied with the reaction of his audience, Abu continued his story.

It was a tale of an old man, one Pa in a village deep upcountry. His wife had died during the birth of his only son some forty-something years ago. He never remarried or had more children, even after his son left for Freetown to attend university and then work. He did not farm or tap palm wine like most of the other villagers. He lived on bush meat — mostly grass cutter or guinea pigs, for which he set traps in the thinning forest nearby. He was the only one left in the village now. The others had all moved.

Months before, some foreign men had come together with few local authorities. They came with the news that a precious mineral had been discovered in the region and that these men with their strange tongues were going to extract it from beneath the ground with their big machines. There would be new jobs for the young men in the village, revenue for the government, and all kinds of wonderful things. However, the iron ore was underneath the village, and every household would have to move as soon as possible for the machines to begin their work.

The people were excited by the prospect of mining activities in their village. The officials appeared calculating but quite pleased with themselves, addressing the crowd as if it was election season. They made promises to bring large trucks in the next couple of days during which time the village chief and his elders were to impress their thumbprints on bulky printed sheets accepting the proposal.

When the entourage finally left, the air was filled with enthusiasm and the Pa’s indignation fell like a stray pellet in a nicely steamed pot of wallah rice.

In the following days, there were more frequent visits, construction of temporary blocks, and of course, the arrival of the eagerly anticipated machines. A meeting was summoned and the Pa, being a member of the secret society, was invited to attend. The foreigners had come with very thin envelopes that they called ‘relocation allowances’ for the resettlement of the soon-to-be displaced villagers and ‘monetary crop compensation’ for their farms. They also had thicker brown envelopes for the local authorities as appreciation gestures.

The Pa did not like it at all. It felt rushed, wrong and he made it known. He thanked the dignitaries, said his piece, turned down the envelope, and swore to his ancestors that he would never move.

The air was tense as he left and soon the meeting concluded. The insistence of the Pa stifled further negotiations. An ultimatum was given for the deal to be concluded within seven days or all the envelopes would be taken away.

Meanwhile, households were packing up and moving to stay with relatives in nearby villages or settling in a new area. The youth excitedly exchanged stories and tips of skilled employment. But underneath all this was bubbling anger towards the Pa. He was greeted each morning by a deposit of feces at his doorstep, met with nasty glances, and was the subject of multiple curses and threats. The leaders came to him offering more compensation, but his silent disobedience never wavered.

On the seventh day, the Pa remained defiant.

He had to go.

As the sun set and darkness covered the deserted village, shadows crept into the Pa’s hut. It came too quickly for the Pa to call out. The heavy blows met his skull and sunk his lifeless body to the ground.

“Aaaaaaah!” Abu’s siblings chorused. It was over. Tomorrow, life will continue for the rest of the villagers. Or so they thought.

The crows of cocks in the new settlement could barely be heard as the rumble of the machines masked the air with not only constant drilling, banging, and humming sounds but with repulsive dust and soot particles. Meanwhile, by the afternoon, the young men who had left before dawn to start their first day of work returned with unpleasant expressions and dashed expectations. They found that recruitment was not automatic. They would have to endure rigorous health checks, education appraisals, and even skill training in instances where the company had no alternative. Till then, workers from other areas where the company had operated will operate the machines. Maybe few would be hired to do menial work for meager pay.

The dramatics of the day were climaxed by the arrival of Santigie or rather Santos as he now preferred to be called, the Pa's son. Santos announced that he had come to take his father with him since the Pa had expressed unease about the move. Although they offered to take him through the makeshift path that led to the old village, they were less generous with giving him an explanation about the Pa’s whereabouts. Met with unanswered questions, heavy sighs, and the sight of the rubble where the hut once stood, Santos began to breathe heavily, his expression of confusion morphed into something darker. Not mere rage, but rather a haunted look of a man passed the point of no return.

Although he had moved away, Santos still held on to his traditions and as he stomped off that night, he placed his index finger on the ground, touched his tongue, and pointed to the sky, swearing to avenge his father.

And that was when he came. Without warning, Konsiloh appeared the following morning with his loyal companion by his side. His ritual did not require engagement with the people. He conferred with the dead. He walked around the settlement, grasping his beads and muttering under his breath. Ignoring the fearful stares of women and men, young and old, he made his way to the center of town where he knelt down, collected some soil, and left.

A heavy silence descended all around and panic quickly spread. The younger children, in their innocence, were bursting with questions; Kosiloh until that day was the object of threats by their parents. The older folks clustered in small groups, which started in whispers but erupted in angry arguments and accusations of whose fault it was. The elders wore grim expressions, exchanging glances but remaining silent.

Abu paused here, feeling the tension rising in the room, he itched to finish the story, but he knew he had to let it unfold in a crescendo. He stood up, took off his shirt, and used it to fan himself in a twirling motion. “Eeee Abu!” Iye, who was only a year younger than Abu exclaimed, tugging on his shorts. Satisfied with this response, he continued.

Konsiloh returned the following day, but the elders told him that he was not allowed to continue his rituals. Konsiloh assured them that only the guilty would be punished. They insisted, offering him double payment for him to turn a blind eye. At this, Konsiloh became angry and refused their offer. In response, he reached into his bag, took out a small sharp knife, and slit the throat of the spotless white chicken he held in his right hand. He spat on the ground, shook the dust off his sandals, and left.

Then it began. For six weeks, every Sunday evening, in a household, the youngest child fell ill. He or she would start with a high fever followed by an outbreak of stinking putrid sores. Regardless of what treatment regimen was dispensed, the child would die three days later. After burying the sixth child, the community came together and decided to consult Konsiloh. They returned with heaviness. Konsiloh had perceived their offer of a bribe as great disrespect. Having been prevented from investigating and punishing the guilty, everyone will have to pay.

So, one after the other, children in the village died until every household was immersed in grief. Even worse was the guilt that each villager felt that they may have been somewhat responsible for the chain of events leading up to Konsiloh’s curse.

In these weeks, only a handful of men were employed by the company, with the majority discarded for fitness ineptitude or some other reason, and none drove tractors or trucks or anything at all. The bush surrounding the new settlement was difficult to till and bore low yields. The brown paper envelopes thinned and quickly emptied.

Soon the young, able-bodied ones left for the city. There was no reason to stay. While the mining continued, the air got thicker with toxic emissions making the few that stayed behind sicker as time passed. Health complaints predominantly of loss of sight and impotence were rampant in the community. Complaints to the district council and other big men fell on deaf ears and soon the new settlement was no more.

“Aye bo” Iye gasped, cuddling a tearful Amie, saddened by the tragic end.

Ebunoluwa was born to be a teacher. She makes time to enjoy writing and telling stories, through poems, pieces and short stories. As an incurable optimist, she uses writing as a means to create spaces in time for the things she so deeply feels and believes. You can follow her work on Instagram: @ebunoluwa_finda and Twitter: @EbunOluwaFinda

Last Tooth II

Third and Fourth

Muvs lost the third tooth during that delicate-butterfly age when you weren't quite sure if you were seven or eight years old.

It happened at night, the losing of the tooth, while he munched his cereal. He squealed to himself. His eyes gleamed and sparkled, as he watched the tooth in his newly freed hand.

He'd get to meet the spirit again. The friendstuff they'd do!

Six months had passed since they last met. The most interesting encounter to have happened to the boy - so magical, so everything his daddy called nonsense. He'd liked the spirit, on the spot; how he'd fought to seem so scary, but wasn't, even with his half-eaten nose and long, rat mouth. He hadn't let Arataman know, anyway, that he liked him. All who've known he liked them, went away, or wouldn't like him in return.

However, he had to wait to meet the spirit again. The clock had leaped past nine, and his daddy had come home, doors and gates bolted shut. And his mom cozied up on the couch, dozing off. He dared not wake her.

Like gold or diamond, or love, he wrapped the tooth up in a clean piece of paper and kept it in the pocket over his heart.

Next evening: "Arata tek yu rɔtin tit. Gi mi mi fayn tit" chanted the boy. He launched his offering to the rooftop. And he waited, lightly bouncing on his toes.

A low rumble. A scratching noise. Then there he was, peering down from the roof, eyes like lakes of oil.

The boy smiled at Arataman, flashing him his gaps.

The collector smiled back, one of those smiles at war with the eyes. He took out a purse. He opened it, showed the boy his tooth amongst other teeth. It laid as any of its companions, pearl-white and small.

But Muvs knew it as his, as you'd know your shadow, even if it clung to someone else.

Then Arataman left. Disappeared into the fog.

"But he promised." Sadness knifed the boy's chest. He looked down at the play cards he'd brought with him. He'd hoped Arataman would stay, set him on the roof, and they'd play and talk. At school, he was a misfit and sat alone in class and at lunchtime. At home, an only child. And his daddy was hardly around and, on days he was, he spoke only a few words to him, mostly Nonsense & Stop That, Naughty Boy. And his mom… his mom… sometimes, she loved him very much, but, most times, she didn't, and only shouted and scolded and cried about her life. Muvs had hoped the spirit would stay, you see, so he'd have a friend for a while.

At the fourth tooth, his dream came true.

This tooth had come out prematurely. It had only been loose for a few weeks. But the boy, on one late Saturday's afternoon, up from a nap, laid poking at it with his tongue. He poked too hard. He winced in pain. And he bled. Then the tooth dropped out. He stumbled off to his mom, hand on his mouth.

"God. Just rinse," she told him upon seeing the blood. "Rinse with water." She leafed to the next page of her bible, her new-found love, paying no more heed to her son.

And Muvs rinsed his mouth and cleaned up, and went out to his spot. He said the thing. Then sent a piece of himself upwards.

The lonely roof grumbled, but not due to the stiff harmattan wind - he was coming, and there he was. Arataman displayed to the boy all teeth collected from him, safe and sound. Promise kept. He had almost disappeared again, when he heard it, a whisper, a plea, from the child.

"Stay. Please, Mr. Arataman."

In that whisper, the ancient collector heard pain, loneliness, and a longing to be held. Adults knew of their depression brought on by bills and failed love stories, mid-life crisis. But they all tend to forget of the storm and darkness that could creep on children, too. And even those who had once gone through that storm and darkness grew up only to forget. A harrowing thing. How would the broken children ever be understood, be held? How would the neglected ever be heard, and not called naughty?

Arataman's promise to the kid had been to show him his lost teeth, and do friendstuff. A smile qualified as a friend-thing; a friend-thing you could do from afar.

But the child needed more than just a smile.

So, Arataman stayed.

Next thing, zinc-sheets beneath Muvs boots. He staggered, finding his balance on the roof.

Arataman stooped close by, petting pigeons. "You know: they forget me. I feed them today, they forget and run from me tomorrow," he said, idly.

"Oh," said the boy.

Arataman stretched, unfolded, and faced him. "What's up?" he said, odd, but ready to listen.

And Muvs had much to say.

He'd started a new year in school, and he hated it. He hated how he couldn't see the hills from the classroom, and daydream. And he hated how he was always alone. He hated how his classmates made fun of his ears and how when he'd report to the P.E teacher, Mr. Martins, he'd only say: Ah, baby Muvs, that's just school! He hated that Abdul, his best friend, had gone to a new school. And, sometimes, he wished to skip classes. Though not for all these things he hated. But for Aunty-Mrs. Neville. His headmistress and new class teacher. A short, stout woman, with a potato face and cherry-red cheeks everlastingly blushing.

"She beats. Sneeze too hard, she beats you. Yawn, beats. She has a fat cane and fat arms. Sleep in class, beats. Cry for being beat, beats! I call her Aunty-Mrs. Neville the real devil. But I'm sure the devil takes notes from her! She tells us to call it pensol instead of pencil, beats us if we don't. I'm afraid of her. And she beat me so bad once cause I had no money to buy the meatballs she brings to class!"

"And what did your parents do?"

"Oh. Nothing." Pain echoed in his answer. "My mom only held me and cried. And told me daddy wasn't treating her right, and she was going to leave him. And went on and on about how the witches in her family will be happy now. And, daddy, he said I was lying. And he'd beat that lying out of me."

Silence tarried between the boy and the collector. A dog barked, faint and far, at a passerby.

Muvs continued his laments, as the diamond sun arched on towards the sea. He spoke so freely, but in his short stops here and there, his glancing of the spirit, waiting for a Shut Up, or a Nobody Cares, you could tell too many people had failed him, ignored him.

And in the way conversations flowed, Arataman asked the boy after a while, "What do you love to do? Tell me about that."

"Oh, I love this. Being here, on the roof, and being heard. I love reading books. And playing with puppy dogs. Climbing things. Um…and sweets, eating them! Not much I guess. You?"

"Listen," said the spirit, hoping his words would ease the hurt budding in the boy. "I won't tell you life gets better. But someday you will experience the joy that surpasses all this pain you feel now and will ever feel. You might find it in the little things, like in a girl, or boy. In a book. In a movie that breaks and mends your heart. You may be stuck here for a while, with horrid parents and teachers and friends, all growing pains. But there is so much you are yet to meet. Much more to the world. All these things you love, you are going to love some more. It will not be like this forever. Hang in there, my friend."

Muvs, only eight years old, listened and, young as he was, understood. "Mr. Arataman, I don't know what to say."

"Remember that."

And so the friends lazed beside each other, chattered and bonded over childish talks, as they looked up at the pinking clouds.

Victor Osman Forna is a writer and poet based in Freetown, Sierra Leone.