"I'm deeply enamored of Sierra Leone "-Syl Cheney-Coker on Writing through Exile

Syl Cheney-Coker is a Sierra Leonean poet, novelist, and journalist. Born in Freetown in 1945, he was educated at the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Oregon, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He returned to Sierra Leone but went into exile in the 90s after he was targeted by the government. Cheney-Coker is the author of several novels and anthologies including The Last Harmattan of Alusine Dunbar, which won the Africa region of the 1991 Commonwealth Writers' Prize. He now spends his time between the US and Sierra Leone. In this interview, he talks to the Poda-Poda Stories team about how literature shaped his work and writing through exile.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ngozi: Your memoir, Jollof Boy: The Early Years, was released this year. It is a rich account of Sierra Leone during the colonial era when you were a child. Why now? Why have you decided to share these stories with us in your memoir at this time?

Cheney Coker: I never really thought about writing my memoir. The best way to get to know anybody is through an account of what we see about our society and whatever contribution we may have made. And in my case, being a writer, I felt that I have been doing that through my books.

However, last year, Mallam O, the publisher of the Sierra Leone Writers Series, said to me “have you started writing your memoir?” So I thought about it and said, why not? Especially as Sierra Leone is not the Sierra Leone it was before. So seeing where we are at the moment- an incredibly bankrupt society-I just felt that perhaps I should go ahead and write this memoir and reflect on a period of glory. It was not perfect, but I think it was better.

Ngozi: You've gone into exile because of your work as a writer in Sierra Leone. Can you talk about how being in exile changed your relationship with Sierra Leone over time?

Cheney Coker: I always tell people that I never left the country, because it is Sierra Leone that gives validation to my being a writer. Without Sierra Leone as a stimulus, I wouldn't be a writer and I don't want to be a writer that is not tied to my heritage. I'm sure you've been reading African literature quite a lot. The current scope of African writers, mainly those under 50, delight in bashing the African continent. They're all writing about an escape from their various problems and the problems of society into which they were born. They’re coming to the West and saying “take me, give me a new name.Things are so bad in my country!”

But it's the madness of escapism.

My relationship with Sierra Leone has not changed and it will never ever change because as I speak to you right now, we are putting the finishing touches to my house on Leicester Hill. I don't know how many more days I have left on this planet so I'm looking forward to going home to reconnect with what is still there.

Of course, I'm not unaware of the fact that a lot has changed. For a start, the landscape has changed. In addition to destroying all moral values, we’ve also destroyed the ecology and the environment of our society. Everything has been chopped out while we delight in being a barren landscape. And we have all of these ugly metallic buildings, concrete buildings going up. So Freetown has become, in my view, a concrete jungle and it's not what I expected Freetown to be like because I've been to other African capital cities and it's not like that.

Having said that, I'm going home hopefully sometime this year. For good.

Charmaine: I recently graduated from an MFA program in creative writing from Texas State University and a conversation that kept coming up among us African students was how much someone's writing changes based on geography. One Nigerian classmate in particular, felt that being in America stifled his writing which is usually set at home in Nigeria. Could you speak to this: do you think wherever the writer is geographically affects the quality and the content of their work?

Cheney Coker: Congratulations on doing your MFA! Having said that, I don't believe that an MFA makes someone a writer. I think an MFA allows you to teach, particularly.

To be a writer is to be consumed by passion that no other expressive cultural form does to you because writing is a lonely vocation, as opposed to being a composer, a musician, or a painter. A painter has a palette and she begins to draw to paint images and colors. A composer or musician has an instrument, and the instrument talks back to you, right? But a writer, you wake up in the morning and all you have is a blank screen, or in my day before computers came to be, you have a blank piece of paper, which you've got to fill with words, and those words must be extremely very close to you. One thing the writer does not want to do is to lie to himself or herself because literature can be extremely vindictive and very treacherous. So writers who think that they can lie about their heritage or their experience just to fulfill a publisher's request are making a mistake. It's always going to be terrible when it comes out.

“My soul is that of a poet’s.”

Syl Cheney-Coker

So my response to that is that it depends on what background the writer is coming from. Nigerian writers of my generation came from a very rich background and it didn't matter where they were. Take Wole Soyinka for instance, who spent many years in exile and still wrote some of the greatest plays like Death and The King’s Horseman, which are about his Nigerian heritage and his perception of what Nigeria was going through at various periods. No one could draw a line between whether they were written in Nigeria or written abroad. I have been in exile for a good many years and I have still been able to write about Sierra Leone. Emotionally and culturally, I'm very deeply enamored of Sierra Leone and I'm very deeply enamored of the background that I inherited.

So, it all depends on whether you bring your country or your heritage with you when you leave, or whether as soon as you get out and step into the so-called melting pot, you feel like you must become someone else.

Charmaine: What authors, poets and novelists shaped your journey as a writer when you were growing up?

Cheney-Coker: African literature was not taught in schools during my time. We went through the grinding machine of colonial education. So strictly speaking, the two people who shaped my perception into being a writer, were writer and physician, Raymond Sarif Easmon, and then the journalist Ibrahim Taqi, who was sent to the gallows by (then president) Siaka Stevens.

I never really fancied myself becoming a writer. I actually wanted to be a journalist. I came to the United States during the sixties, and it was the period the Harlem Renaissance was being brought back into being, and all the writers, like James Baldwin were being taught. Of course David Diop and Leopold Senghor had all become part of the Negritude Movement and we were all being swept up into consciousness by what was going on at that time. That’s when I realised there was something in me that was empty.

I also felt that my Krio identity was not any different compared to the Harlem Renaissance or the Negritude school. I had been fed a lot of crap by colonial education and there was a subterranean journey that I had to undertake to find myself. That journey could only be achieved by becoming a writer.

Charmaine: What were some taproot texts that inspired you to became a writer? And you’ve written poetry, creative nonfiction and novels. Which form have you most enjoyed writing in?

Cheney-Coker: I’ll answer the second question first. My soul is that of a poet’s. I think anyone reading my work would realize that. Even in my memoir you can see that it's of a poet writing. I express myself much more passionately in my poetry, because it's personal to me. Fiction gives me an opportunity to write about the collective in a wider and more dramatic format.

To the first question, when I started writing poetry, I discovered Leopold Senghor and other negritude poets and my favorite for a long time was the great Congolese poet Tchicaya U Tam'si. He's probably the most famous French writing poet at that time from Africa. Then there was the great Peruvian poet César Vallejo whose poems I really love. The English speaking writer I admired the most because of his approach to landscape and someone's existential crisis, is the Australian writer Patrick White, particularly his books Voss and The Tree of Man. It was Patrick White who showed me that it's possible to look at a vast landscape that has not been populated before and to try to make sense of it.

I also like One Hundred Years of Solitude. When I read the first page I thought “oh my God, this is an African book!”And what Gabriel García Márquez taught me was that it is possible to write a political novel and infuse it with magic and culture.It is possible to write a political novel that is not boring.

Ngozi: I remember reading your poem, the Colour of Stones, and just marveling at the beautiful imagery that you used to describe our culture. Can you just comment on how you've examined the interiority of Sierra Leonean lives in your work?

Cheney-Coker: Culture becomes extremely central when I write about Sierra Leone. It isn't just my own immediate culture, but the general culture as a whole. I'm deeply enamored of all the cultures of my country and I may not speak the other languages, but I recognize their beauty and validity because this is what makes Africa as a continent extremely very important and different from other societies.

We are truly in the real sense of the word, a melting pot, but we don't destroy the individual ingredients that contribute to that melting pot. It's like in Sierra Leone, we have plasas, but you would taste the efo nyori, or cassava leaves or egusi.

And so I recognize the nature of our cultural dynamics. For example, when I visit a place like Port Loko, I'm not looking for the influence of Freetown in Port Loko. I'm looking for Port Loko in Port Loko. I'm also very particular about expressing the culture which I was raised in. I try my best to recollect, to re-narrate and to express as best as possible the chapters and the passages that, my mother especially, passed down to me. And I hope she'll be very proud of me. Infact she was the inspiration behind the character, Jeanette Cromantine in The Last Harmattan of Alusine Dunbar.

Ngozi: What a beautiful tribute to her! And that’s a great segue to the next question. The Last Harmattan of Alusine Dunbar recently went into reprint and Charmaine and I have our copies! The book tackles a lot of themes like the effects of the Trans Atlantic Slave trade and nation building. What does it mean for you for this book to go into reprint?

Cheney-Coker: I'll tell you a story about Alusine Dunbar. In 2012 or thereabouts, I was at the University of West Virginia in Morgantown. I was the keynote speaker at this conference and a woman came up to me and said “do you know how much I paid for this copy when I realized you were going to be the keynote speaker because I wanted you to autograph this book for me?” The book was selling for anything between five hundred and a thousand dollars! And not one penny came to me. I don't know how this happened.

Ngozi: Yeah, I was looking for a copy on eBay and it was around that price, so I had just given up.

Cheney-Coker: Yeah, and not one penny came to me. I would get so mad I would say, how is it possible that my book is being reproduced and people were selling it online. But anyway, The Last Harmattan of Alusine Dunbar is back. It never should have gone out of print. And so it was this new publishing house at Bloomsbury who bought some of the rights of the Heineman books.They reached out to me and said they would like to republish it. So I am glad Alusine Dunbar is back in publication and circulation and I plan to bring some copies to Sierra Leone later this year.

Anyway, how do I see some of the things related to Sierra Leone today? When you get towards the end of Alusine Dunbar, about 30 years ago, I started predicting that what is happening now, was going to happen. I saw the collapse of all moral values. I saw the greed and hunger in our intellectuals who were always sitting by their telephones waiting for calls. In those days there were only landlines. They were sitting by their telephones waiting for a call from Siaka Stevens or Saidu Momoh, so they could abandon teaching, and become ministers, et cetera, et cetera, so they could line up their pockets.

But I'm happy to see that your generation is changing everything. I'm happy there are so many writers in Sierra Leone right now, especially the poets, writers and editors like you and that is the greatest reward to me as a writer. It is not in the many books I’ve written or the dissertations on my work. What brings me the greatest joy, and I mean that sincerely, is to see that in my lifetime, there are so many promising young writers in Sierra Leone, especially women. I would not have thought this possible, given the destructive influence that my generation and the generation immediately after mine imposed on Sierra Leone. Because what is going on now is toxic. Not even the worst days of Albert Margai were like this.

Now people are afraid. I get letters from people who say they are afraid. Since when did we become a society where people are afraid to communicate? We are supposed to be a society where regardless of where we are from, we are one nation, one country, one people, and that is what makes Sierra Leone unique.

Charmaine: What is your advice to young Sierra Leonean writers?

Cheney-Coker: The epochs are different. By which I mean, I came into writing at a different epoch, and so my narrative is different. And you're writing during a completely disorganized and dysfunctional period where all the threads that held our society together - and this applies to Nigeria, to Kenya, Cameroon or Senegal - have disappeared. But in those other societies, they have not disappeared as they have been allowed to in Sierra Leone. There is still some semblance of cultural preservation and societal responsibilities that we no longer have in Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone is a complete collapse of anything pertaining to the maintenance and the integrity of the state, and that is what frightens me.

So, your generation has a much more difficult task than my generation did. We had a lot to feed on. Ours was an expressive period. We were expressing the norms and the passions and the traditions of society. You are now singularly charged with rebuilding society.

The other problem you have to contend with is publication. There's only a small publishing house in Sierra Leone. So, we need more publishing houses but also we need a couple of good bookshops. There's not a single good bookshop in Freetown, which is a shame! I hope other Sierra Leoneans will invest and support publishing in Sierra Leone.

Ngozi: Something we always ask writers we talk to is how has writing saved your life?

Cheney-Coker: Without writing, I probably would be dead. I could not become a doctor because the only branches of medicine that I like are pediatrics and veterinary medicine and I can’t stand seeing children and animals suffer. I hate the legal profession. I've not balanced my checkbook in the last twenty years, so I could not have become an accountant.

So, writing saved my life in the sense that it gave me a dimension to express myself about my society and my role, without my drinking myself to death if I had done something else. And it’s also saved my life in the sense that it has exposed me to the validity of other societies, to other people and other traditions which have made me much more humane.

I cannot tell you how grateful I am that I can write and express myself in that way. Writing imposed itself on me in the sense that I never set out to be a poet or a novelist. It is just that I found that when faced with a particular situation to express myself, I picked up my pen and I started writing.

The Last Harmattan of Alusine Dunbar is available to purchase from Bloomsbury. Sacred River is available to purchase from Barnes and Noble. Jollof Boy and other books by Cheney-Coker are available to purchase from the Sierra Leone Writers Series.

"A professional opportunity"- Poda -Poda Stories Fellow Sulaiman Bonnie's reflection

The Poda-Poda Stories Fellowship is a year-long program that is designed to support young Sierra Leonean writers to grow in the literary industry and manage an independent creative project.

The goal of the fellowship is to inspire and train the next generation of young writers in Sierra Leone. Through access to resources, coaching, training, and support for their independent projects, we hope that fellows will enhance their creative skills, while gaining exposure to the literary world of publishing, writing and editing.

Poda -Poda Stories Inaugural Fellow Sulaiman Bonnie reflects on his work over the past year and talks about his independent project— an anthology of poems from students.

Isatu Harrison on Building Creative Spaces in Sierra Leone

Creative Hub Africa is a space in Freetown where creatives learn and connect with each other and explore potential markets for their creative businesses. The founder says their goal is to unlock the creative potential and build an entrepreneurial mindset in Sierra Leone's growing youthful population, which is almost 80% of the country's population. The hub also hosts creative events like open mic nights, which bring together poets and writers. Poda-Poda Stories Fellow Josephine Kamara interviewed the founder and CEO, Isatu Harrison, about the importance of creating such a space in Sierra Leone and how it all started.

Isatu Harrison: I was invited to a creative space in the UK. I was so inspired by it as it was such a bold space and I imagined having something like that in Sierra Leone. When I moved back home, I started off with the Izelia factory, a fashion company, and the impact we had on young people was huge. More young people kept approaching me and my team to come to the factory to work. So, we started working with creatives in the Izelia factory and that was because we have a little bit of space that we could play with. And that's how the Creative Hub started.

Josephine Kamara: What gap in the creative ecosystem were you aiming to address?

Harrison: I thought it was important to have a space sharing and creating opportunities for people that want to pursue creative careers. This is a hub for ceatives with ideas who are looking for a space where they can go and flourish and flesh out their ideas out work on them. And this is the gap the Creative Hub is trying to fill – providing a home for all of them.

Kamara: You mentioned something about infrastructure, when you stated that systems for creative people work in the UK and in Sierra Leone, it's almost non-existent or even if it's there, we're not well-structured. Please comment on the creative infrastructure in Sierra Leone.

Harrison: Because most of the population are young people in this country, there is dire need for nurturing ecosystem for them to birth their dreams. When I came back home, the only space that I found was Ballanta Academy. Ballanta has been around for 24 years, so I won’t say nothing exists, but the infrastructure is small. For the Creative Hub, we got a grant from the World Bank and the Government of Sierra Leone. We had a $50,000 grant and I matched that with personal funds. I have no regret in doing it because every day people go into that space to dream, to do creative work, to share their work. I don't have the words to explain how it makes me feel.

Kamara: As you emphasise the importance of providing infrastructure for growth, could you elaborate on the specific resources and support that the hub offers to young creatives in Sierra Leone?

Harrison: So when you go into the space, we have what we call the design space, and that design space is really the space for creatives to get their work done. So we have all the graphic design software loaded on computers so you can do, you know, practice your graphic design. Whether you are an aspiring entrepreneur or just at the ideation stage, we have expert advisors that work with you to develop that idea and turn it into an actual business.

Kamara: We always say that as Sierra Leoneans, we need to tell our stories more. I've attended some of your events, and I've seen great storytellers and poets there. Can you comment more on specific support for young people who use this art form to express themselves.

Harrison: What we want to do next is connect is connect young writers to writers’ programs and workshops. We have a few people interested in working with writers, and we're planning our first MasterClass. On that note, we have some visitors coming this month. I don't know if you've heard of Fela, the play? They have Broadway shows in New York, and the writers have some connection to Sierra Leone. They are really interested in meeting young writers, poets, young people in that sector. They're having a master class possibly on the 21st or 22nd of December. I feel like we have a lot of wealth in terms of writers and directors in the diaspora, and if we connect them with local talent, it could be amazing.

Creative Hub Africa offers a space for young people in the creative sector to network and learn.

Kamara: Oh, that sounds exciting! Are there more initiatives like this within the hub to mentor and give visibility to the creatives that makes use of the Hub?

Harrison: Every last Friday of the month we organise an open mic nigh and we select three people from each performance night. We then connect them to mentors at Ballanta Academy. We also want to get more people involved in the process. Starting this month, people in the audience can vote, and we'll select our top three. Once we have those three people, we're making contacts in Nigeria with CC Hub in Nigeria. CC Hub stands for Co-Creation Hub. It's a creative hub based in Nigeria and present in Kenya. They've been in the space for over 10 years and understand how the creative space operates. They have many opportunities that we don't have access to here. The creative sector is still very young in Sierra Leone, and it's at a stage where we all need to come together to establish it. So, we are collaborating with organisations like CC Hub to help us nurture creatives from Sierra Leone, starting with those from the open mic sessions.

Poda-Poda Stories Fellow Josephine Kamara(L) and Founder of Creative Hub Africa Isatu Harrison at her home.

Kamara: Why is it important for a Hub like this to exist in a country?

Harrison: The trend happening globally is that the creative sector is the fastest-growing economically. In Sierra Leone, either due to lack of awareness or conscious decisions, we haven't prioritised or focused on developing the creative sector. There's so much that can be gained from it, and the space we're creating has a fundamental purpose. It's not just about creating a safe space for creativity but also about formalising it. There's tremendous potential in the creative sector, and we are working and hoping to collaborate with the government and partners to make them realise the significant impact it can have on our country.

Creative Hub Africa offers a space for young people in the creative sector to network and learn.

Kamara: Everything sounds so peachy, but I’m sure challenges exist. Do you want to share some for the people who are interested in learning more about what it takes to build this creative infrastructure in Sierra Leone?

Harrison: I’ll start with the most recent event. So, for Christmas, what we decided to do was bring female entrepreneurs to showcase their products. So, I thought, why not bring these women together and try a digital market where we only accept cashless transactions.

This way, we can introduce them to different technologies available that they can use in running their day-to-day business. We also brought the idea of reducing single-use plastics. Instead of using plastic bags, we encouraged them to use fabric bags. We even created cost-effective fabric bags for them to use for their customers. It's an eco-friendly approach and encourages the use of reusable bags.

Yesterday was the launch of that market (referring to 7th Dec.), and it wasn't without challenges because people aren't used to going anywhere without cash. The shift to mobile money or card payments was very challenging. I think it's the first market of its kind here, that was completely cashless and plastic free.

It was so challenging. People were complaining that the mobile money was not working, but by 6:00 PM, most people were making payments by mobile. I realised what we need in Sierra Leone is to guide people through change. Internet connectivity is another thing we as creatives are gravely challenged with in Sierra Leone.

Kamara: Looking ahead, what are your dreams and aspirations for the creative hub?

Harrison: If we make this a priority, within the next two years we would see so many changes within the creative ecosystem and we would see a lot of creative careers thriving in Sierra Leone.

Josephine Kamara is a Poda Poda Fellow, Feminist Activist and Storyteller who writes to know and share her well-rounded human experience. She is currently a MA candidate at the Institute of Development Studies – University of Sussex, UK.

Mohamed Sheriff on Children's Literature in Sierra Leone

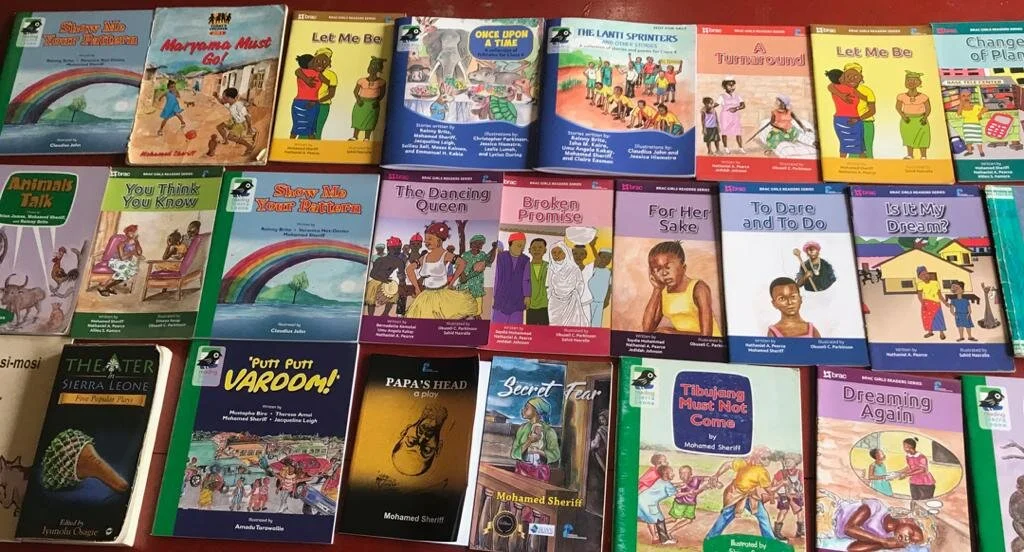

Mohamed Sheriff is a Sierra Leonean children’s story writer, playwright, producer and dramatist. He is the author of several beloved children’s books and novellas from Sierra Leone, including Maryama Must Go and Secret Fear. Mohamed Sheriff has been a trainer, coach and publisher of mainly children books. As a children’s books, writer he has a dozen titles to his name, some of them anthologies; as a publisher he has published twice that number of books by other children’s books writers; and as a trainer and coach, he has worked in a number of book development projects that have seen the publication of up to forty books including anthologies for children. He also owns a communications and media company Pampana Communications Publishing and Media Consultancy.

In this interview, he talks to Poda-Poda Stories about his love for children’s literature, why it is important for Sierra Leonean children to see themselves in stories, and the future of publishing for children’s literature.

Poda- Poda: Thank you Mohamed Sherriff, for joining the poda poda. Please tell us about yourself and your work.

Mohamed Sheriff: I write children books, short stories, novellas, and screen, radio and stage plays. I’ve published several books in all of these categories and won a handful of national and international awards for my writings.

Poda-Poda: So how did you get into writing? Have you always been writing or was it something you branched into?

Mohamed Sherriff( MS): I’ve been writing since I was a kid. I did a lot of writing in my ‘head’ back then. I can say I had a hyperactive imagination that would weave a story at the tap of a button in my head. Some incident or chance happening, commonplace or extraordinary, would fire up my imagination into creating a story. I was inspired to tell stories by my mother and my step mum, who were both very good folk storytellers. In the evenings, especially during the long holidays, we - siblings, cousins, other relatives, even neighbours – mainly children, would gather in our backyard or living room and listen to their stories. I was always enthralled by the way my mother told these stories: she would sing, sway, clap her hands, tap her feet and, most captivating to me, mimic the sound of different characters, including animals in her stories, and transport us into their strange, magical or extraordinary world. That was how my love for stories, drama, books and movies evolved. I admired her storytelling so much that I wanted to be a storyteller like her when I grew up. When I was able to read, I discovered books that had similar stories like my mum told, the folk tales, and other kinds of stories, too - realistic fiction for children, and I loved them all.

The more children books I read, the more I loved the idea of writing for children. And then I started reading more complex literature, like novellas, novels, short story collections and plays. My exposure to those kinds of literature inspired me further, strengthening my resolve and nurturing my dream of becoming a writer.

The inspiration for the other important category of my writing, drama, also came from my childhood experiences. When I was little there was a theatre group in our neighbourhood called Guinness Theatre or Drama Group. I think it was sponsored by Guinness, a beverage company. The group conducted rehearsals in a compound on another street just round the corner from our house. Children would flock to the compound to watch the rehearsal and were allowed to stay as long as we behaved ourselves. We got so involved in watching those rehearsals that some of us knew many parts of the plays by heart. I can still remember some of the lines of some of those plays. We had such fun watching them that again I felt I wanted to be involved in theatre when I grew up.

Poda-Poda: How did you make the decision to go into children’s book specifically?

MS: Considering my wonderful childhood experiences at those storytelling sessions, my passion for reading children books ,it was no accident that when eventually I started writing, children books were among the first and has remained an important part of my work as a writer.

My getting into the business of actual writing for children was triggered by my encounter with Macmillan Publishers. Way back in the mid 90s they were very active in Sierra Leone. They organized a workshop to encourage Sierra Leoneans to write for children. With my passion for writing for children, I saw that as a great opportunity, so I attended the workshop, at the end of which, we were encouraged to submit manuscripts. One of the stories I wrote, “Secret Fear” a novella for young readers went on to win an international award and sold thousands of copies.

Much later, I had the opportunity to meet with an organization called CODE (Canadian Organization for the Development of Education). They invited me to a children’s book development workshop in Liberia, where they were engaging local writers and illustrators to develop their own books. After that workshop, they decided to come to Sierra Leone to launch a similar programme for Sierra Leoneans with me as a co-trainer, facilitator and editor. To date, the programme has published 29 books for children.

Besides writing for children, I have been a trainer, coach and publisher of mainly children books. As a children’s book writer I have a dozen titles of books to my name, some of them anthologies; as a publisher I have published twice that no of books by other children book writers; and as a trainer and coach, I have worked in a number of book development projects that have seen the publication of up to forty books including anthologies for children.

Poda-Poda: You’ve shared how you’ve published several children’s books. How important is it for Sierra Leonean children to have those books in schools?

MS: It is very important for these books to be in schools, because reading is one of the most effective ways to develop a child’s mind. All other things being equal, a child who engages in reading as a hobby is likely to perform better in school overall than a child who does not. Reading helps children in some very important ways: it broadens their horizons and helps develop their critical thinking and communication skills; and all of this will help them in other subject areas too, not just in literature and English. That is why it is important to encourage children to read. And I would encourage them to start by reading Sierra Leonean books. A lot of foreign children books have been brought to Sierra Leone and distributed to libraries and other institutions. Some of these gather dust on shelves because children don’t read them. This is not to say that it’s not important to read books from other places, but first we must get them interested in reading generally. When children read stories that they can relate to, it excites them and gets them more interested in reading in general. This is what we observed when we distributed books to school reading clubs and libraries through one of our book development and reading projects. The feedback was that children enjoyed reading Sierra Leonean readers than foreign books, because they can identify and engage with the stories and characters. So with all the challenges we are facing with education, one way to help our children from scratch is to promote reading and encourage them to read. It’s one way they can develop their minds against all odds. Reading is one way we can help to improve standards of education in Sierra Leone.

Poda-Poda: How can we support more writers to get into children’s literature?

MS: That is what I have been doing for the past twelve years. My organisation Pampana Communications Publishing, PEN Sierra Leone and our international partners have organized workshops to train writers to write for children. Each of these workshops end in developing manuscripts to be published. But then, because resources are limited, we can only publish what available funds allow us to publish. If the government can support these efforts, it will generate a lot of books.

Everyone one has a part to play in promoting reading. It is the responsibility of our ministry of education to put reading top of their agenda to promote quality education. School authorities should show more interest in promoting reading in their schools. They can include reading in their timetables and have a kind of library hour or reading time to encourage children to read on a regular basis. Parents too have an obligation to encourage their children to read. As parents, we should also be reading to our children and introducing them to stories. Even if it is folk stories, like the ones we used to enjoy listening to as children. That would make children interested in stories either oral or written. The demand for books will encourage more people to write.

Poda-Poda: Let us talk about your other work as a playwright. How did you start that and how has that journey been for you?

MS: When I was writing my dissertation in university, among the option of topics we had was, Recent Trends in Sierra Leonean Theatre. I chose that topic without hesitation. With it I saw an opportunity to watch plays, read play scripts and meet with actors, stage crew and directors during the course of my research. By the time I completed my research and wrote my dissertation, I was absolutely certain I was going to be a playwright. Fast forward to where we are now, I have written well over thirty plays for stage, radio and screen and for the purpose of both entertainment and social change. And I have published, staged and screened a number of these plays and won some national and international awards for playwriting in the process.

It’s been quite an interesting but challenging journey. One of the biggest challenges of particularly theatre in the 80s and 90s was an acute lack of venues for theatrical performances. Up until the mid 80s we had the City Hall as the main venue for theatre. The British council auditorium had always been there, but not accessible to everyone. So the City Hall became a hugely popular venue for plays attracting huge crowds from mid week to the end of the week. Unfortunately in the mid 80’s the then Committee of Management in charge of the Freetown City Council placed a ban on performing plays at the City Hall.

The author, Mohamed Sheriff.

Poda-Poda: Why was there a ban?

MS: All I knew was that the head of the committee said that the hall was not for theatre but other important civic functions. That action seriously affected a lot of groups that relied mainly on that hall for their performances. Many groups simply stopped operating.

A few including my company, Pampana, tried to overcome the challenge by switching focus from producing theatre as art entertainment to producing theatre for social change or development on demand from various organisations that paid for our services. Unlike theatre for art entertainment requiring a built up stage with sometimes elaborate sets in a specified venue, theatre for development can be done anywhere there is space – street corners, market places, village centres, town halls and open community fields

So the ban gave those who were resilient and resourceful an opportunity to create and stage plays for community theatre or theatre for development. But for a number of the groups it was either the end of the road or the beginning of a long period of dormancy.

Poda-Poda: What an interesting journey! It is really unfortunate how theatre declined in Sierra Leone. How can we revive this in Sierra Leone?

MS: That’s a very big question! It’s quite a challenge. There are people working behind the scenes to revive it. However, the biggest challenge is that you cannot do this without money. You have the talents, writers, actors, directors and producers, but to mount your play, you need an audience. To get the audience to go back to theatre, that is a big challenge. The economic situation in the country is such that, most people would have to choose between spending 40,000 -50,000 leones on theatre or using it for something more essential like food or transportation. So that’s our biggest challenge. The government or big businesses could help if they wish to. For a start if they could identify four or five reputable groups, who could perform 2-3 plays per year, and provide them with funds for the productions annually, this would allow those groups to sell tickets at affordable prices and give members of the public the opportunity to watch up to 15 plays per year. That way, drama productions could be sustained over time.

Poda-Poda: When you say “the government”, who specifically are you referring to?

MS: The Ministry of Tourism and Culture. I’ve heard in theatrical circles that the Ministry is interested in reviving theatre, and that the minister has called a number of meetings to discuss the way forward. I hope some progress has been made, and I bet one of the main challenges the ministry would also be facing is lack of funds.

One simple way to work towards reviving theatre is to support groups to produce plays on a regular basis.

Poda-Poda: What advice would you give to writers who want to go into playwriting or children’s literature?

MS: I have met many people who see writing as a way of making money. There is nothing wrong with that. Most dream of publishing best sellers. There’s nothing wrong with that too. Nothing wrong with dreaming big. But you must love to write. You must have the passion for it. Initially the love for writing must be stronger than the desire to make money out of it. That love would let you put your heart and soul into your writing and give you your best seller. Thinking about making money above all else could lead to frustration and disappointment in this field.

To develop excellent writing skills, you must read and keep reading and keep writing. Read, read, read, and write, write, write. And do that with a lot of love. Somewhere along the way, your talent would flourish and be recognized.

Also with so much competition these days, it would be helpful to look at innovative ways you can market your works besides relying on the publisher alone. But first you must develop your skills as a writer.

To buy Mohamed Sheriff’s books, contact him at 82 Sanders Street, Freetown, email him at msaydia@gmail.com or call 076612614.

Interview by Ngozi Cole