A Writer's Insight: Pede Hollist Talks To Poda-Poda Stories

Pede Hollist is a Sierra Leonean writer and a professor of English at the University of Tampa, Florida. His short story, “Foreign Aid,” was shortlisted for the 2013 Caine Prize, arguably Africa’s most prestigious literary award. His first novel, So the Path Does Not Die (Jacarandabooksartsmusic, U.K.), won the 2014 African Literature Association’s Book of the Year Award: Creative Writing, and his short stories have been published in several platforms. Pede Hollist shared his journey with Poda-Poda Stories in this interview.

Poda- Poda: Please tell us a bit about yourself (background, your work as a writer, academic, etc.)

Pede: My name is Arthur Onipede Hollist, but I write as Pede Hollist. I was born in Freetown, Sierra Leone. I am currently a professor of English at the University of Tampa, where I teach academic and creative writing as well as African Literature.

Poda-Poda: You have rich collection of work (including a short story that was shortlisted for the Caine Prize). Tell us how you started out as a writer.

Pede: I stumbled into writing fiction in my late forties. Apparently, I often told amusing tales to my department colleagues. One of them encouraged me to convert them into written stories. I did, and Path, my first novel, was the result. I would not encourage beginning writers to skip the apprenticeship of short fiction and nonfiction narratives because writing a book is a mammoth task. Still, determination can overcome most challenges. Before writing, I mostly read. By the end of primary school, I had read all of the 20-book children’s classics my parents bought for my siblings and me. After I completed them, I started reading the entries of the adjacent encyclopedias. No, I did not read all of them! Instead, I played cricket, football, and ran track. Diverse interests and activities enrich one’s outlook and provide a deep fund of experiences to tap into when writing. In secondary school in the UK and Sierra Leone, I read the novels of Richard Gordon, P. G. Wodehouse, and James Hadley Chase. Of course, as a college student and now as a professor, I read a broad range of literary texts. Reading enabled me to become a writer.

Poda-Poda: Tell us a bit about your writing process.

Pede: I am always looking for ideas and incidents to turn into stories. I take notes , do research, and free-write if an angle or insight on a subject grabs me. My phone is full of catchy phrases, quotations, and well-written sentences. I read books in print and e-formats, listen to audiobooks, and attend author readings. I daily listen to the news, to people telling stories, and to stand-up comedians. I learn from them the importance of set ups, timing, pacing, and punch lines. These elements help me to create engaging, suspenseful writing. Of course, having an idea does not mean you have a story. I spend hours, sometimes days, months, and even years shaping ideas to make them fit with others for a story. For example, an idea for a recent short story titled “Where One Thing Stands” came to me in 2009 when I visited northern Ghana. There, I learned about a longstanding land dispute between the Namogligo and Tindongo peoples. It had resulted in periodic, deadly engagements between the two groups. I wanted to write about this conflict, but I did not feel the subject would make an interesting short story. The idea floated in my head until 2016 when I met a person who self-described as gender neutral and was searching for acceptance from family and friends. After some research, I combined this individual’s desire with the dispute between the warring ethnic groups into a story about difference, conflict, and coexistence. Of course, this process works best when you have time. Often though, you have to shoehorn your ideas into a story because you have a deadline to meet. I can do that too. So the takeaway is, be adaptable.

Poda-Poda: Your novel, So The Path Does Not Die, focuses on home and exile and belonging to a place. It also touches on certain "sensitive topics." How important do you think it is to address what would be considered sensitive topics in literature (e.g, FGM, ethnic discrimination, war trauma, etc.) through literature?

Pede: Very important, but I don’t think that should be the goal of writing literature. People don’t read novels and poems because they want to learn about sensitive topics. They read because they want to be immersed in an aesthetic experience. Hopefully, careful handling by authors of the subjects mentioned in your question exposes readers to insights without putting them under pressure to take positions and make judgments. My goal in telling stories, sometimes with a smile and at other times a snarl, is to show that issues are more complex than we imagine.

With that goal, I stay alert to places where I may be engaging in agenda-writing. To ensure I accurately and ethically represent groups of people and thoughtfully deal with sensitive subjects, I do my research. For example, before and during the writing of Path, I read Michael Jackson’s Allegories of the Wilderness, other ethnographic studies of the Kuranko, and interviewed several of its members. To get a comprehensive understanding of circumcision, I read many articles, especially those of Fuambai Sia Ahmadu, a robust defender of the practice, interviewed, and surveyed many people. Over time, I was able to inhabit the different perspectives before reproducing them through character and dialogue. Yet at a literary event in Kenya, one audience member told me that my story did not advocate for stopping FGC and noted that was an attitude those of us who lived in the west could afford to adopt. So, regardless of your efforts, readers engage your work with biases and agendas, and insensitivities arise where you might have intended none.

Poda-Poda: Your short story Foreign Aid was shortlisted for the Caine Prize. Please share the process of how it happened.

Pede: Like many other Africans, I have listened to the arguments about the pitfalls of foreign aid. Many Africans returning to their birth lands from the diaspora have functioned as donors and bearers “of aid.” I am one among many. In the native land, we consciously or unconsciously play up our “overseas-ness” and benevolence, sometimes to show off, but often in response to an overwhelming presence of material poverty and need. However, we quickly realize that our assistance is inadequate or misused. Take the laptop gifted to a nephew, niece, or friend, sometimes with much fanfare. Not long after, we learn the device is no longer working. It fell and the screen broke, got soaked by torrential rain, was fried by power surges, or ravaged by viruses (including older strains of the Coronavirus). These things happened to it serially. For each, you send replacement parts and money for repairs. Then it got stolen! Talks about a new waterproof, fire-resistant model with the latest antivirus and updates are underway. But donor fatigue is setting in. Oh, did I say I wrote the story because I wanted to laugh at myself, other donors and recipients who have been through this aid experience ? If readers recognize the parallels between personal and international assistance, and that tangled motives, interests, and personalities underline and undermine giving, that’s a good outcome.

Poda-Poda: How can more Sierra Leonean writers bring or highlight their work on international platforms?

Pede: They must present well-edited works to the curators of international platforms. Because all writers suffer from word blindness, hand over your manuscript to skilled editors or experienced writers. They will point out inconsistencies with the subject matter, plot, and characterization. They will identify opportunities to improve craft elements, grammar errors, typos, and format issues, especially those pesky ones that pop up in editing.

Join Facebook communities of writers, editors, and publishers and develop relationships. Subscribe to platforms that publish contemporary African writing. Submit your work to them. My favorite is Afreada. It presents a range of exciting, relatable, and easy-to-read stories. It even tells you how long it would take to read each story, typically from three to eight minutes. Read those stories and the responses to them to get a sense of the themes, issues, and styles that are current and appealing. Imitate them for sure, but to catch attention, you have to break away from popular trends and do something different.

Regularly visit the websites of your favorite authors and follow them on Twitter and Instagram. To keep current with what’s happening in the field, subscribe to James Murua's Literature Blog. It has a country section and a comprehensive list of competitions and publishers. Submit your work to as many sites as possible, making sure you respect those that do not accept simultaneous submissions. I recently learned of Rigorous, “a journal written and edited by people of color.” However, be prepared that you are not going to be placed or listed more times than you are. Stiffen yourself for the rejections. Brush them off and keep writing, revising, and submitting.

Poda-Poda: How can Sierra Leonean creatives (both at home and in the diaspora) collaborate to bring our rich literature to international platforms, or should we focus on building a strong literary scene in Sierra Leone first?

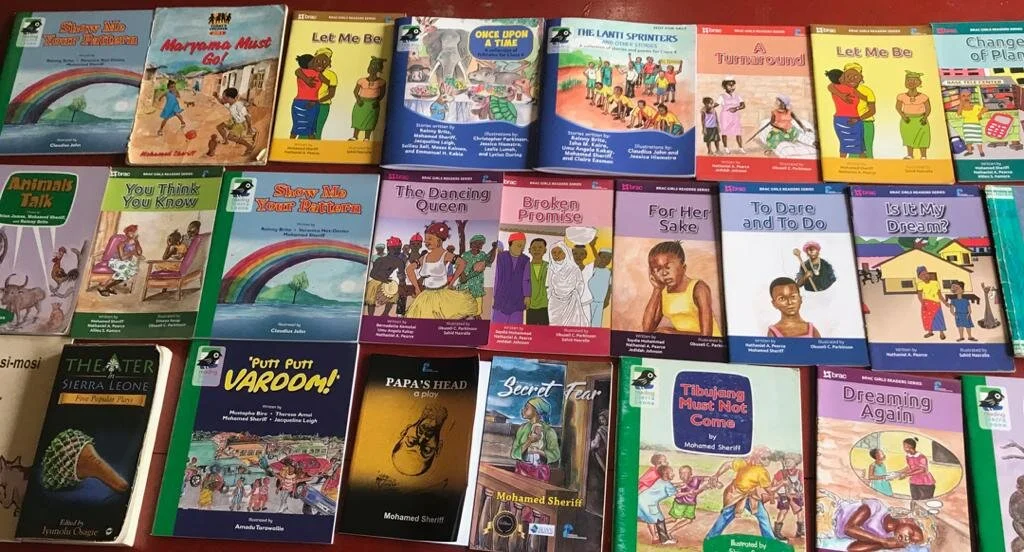

Pede: Yes, focus on strengthening the workshops, competitions, artists’ organizations, and festivals already in place and collaborating to extend them throughout the country. Showcasing the country’s rich literature is the product of good writing. Nigerians, Kenyans, and South Africans dominate the African literary scene because they have more established creative writing cultures-frequent workshops and author readings, more secondary school and college elective courses, competitions, publishers, and websites.

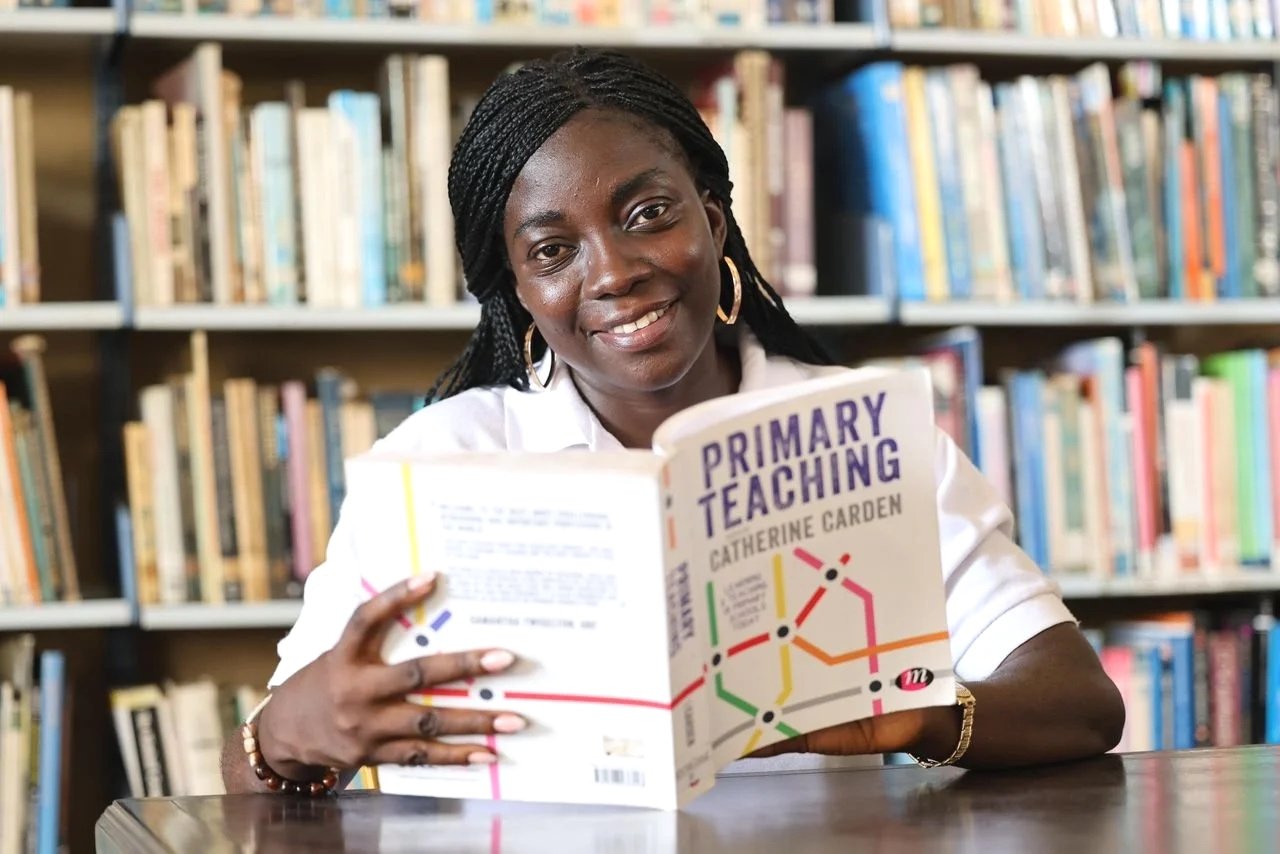

During my 2017-2018 Fulbright year in Sierra Leone, I conducted workshops at Modern High School, Harford Girls School (the one on Circular Road, Freetown), and at a community program named Bright Light Youth Empowerment. The students in these sessions were enthusiastic and had stories to tell. Their curiosity, interests, and talents have to be sustained and developed. We need more competitions such as those offered by Aminatta Forna and Nadia Maddy, book festivals, and reading clubs.

To that end, I am going to be starting my literary blog. It will be another space for Sierra Leoneans to display their work. If we build such sites with quality material, the international audience will come to read our rich literature. Then we should host in-country writers’ retreats. I would love to be part of a two-week residency somewhere in the hills of Kambia. That’s a project to collaborate on.

Poda-Poda: What advice would you give to young creative writers living in Sierra Leone?

Pede: Study Sierra Leone’s cultures, arts, and histories. Pay close attention to the trends today, especially among your peers. Write about them, not to teach, preach, and engage in social criticism, but to immerse your readers in the worlds or subcultures you create. Write in Mende, Temne, Krio and other local languages, or lightly incorporate indigenous vocabulary, expressions such as fiam and kitikata and intensifiers like o and ya into your English-language pieces. Incorporate oral storytelling stylistics like repetition, parallelism, piling and association into your writing. Play and experiment.

Read beyond the contemporary African, British, and American texts that are taught in schools and colleges. Africa’s Sunjata and Mwindo epics, India’s The Ramayana and The Mahabharata, Japan’s The Tale of the Genji and The Tale of the Heike, and China’s The Book of Songs are a few examples of the breadth of world literature that could help your writing.

Become a voracious consumer of non-literary material. Knowing about economics, accounting, anatomy, cosplay, gender issues, psychology, and a thousand and one other topics can be surprisingly helpful when you are writing. Look on Youtube and Google videos that teach about writing.

Don’t make excuses about not having the time to write.Write, every day, until you have a completed draft. Then revise until you believe it is the next great work the world has been waiting for. Finally, send it to skilled readers who will tell you the work can’t possibly go out into the world as currently dressed-- you know, like your parents said to you when you wore that gaudy shirt or revealing dress. The experienced readers will have suggestions and comments that will make your great work better. Still, don’t change your narrative because someone thinks you should. Weigh suggestions, use and adopt what feels right, and set aside what doesn’t. You will get rejection letters (many of them) and fail to place in competitions. Don’t give up. Keep writing. Success is around the corner.