Letters Across the Diaspora

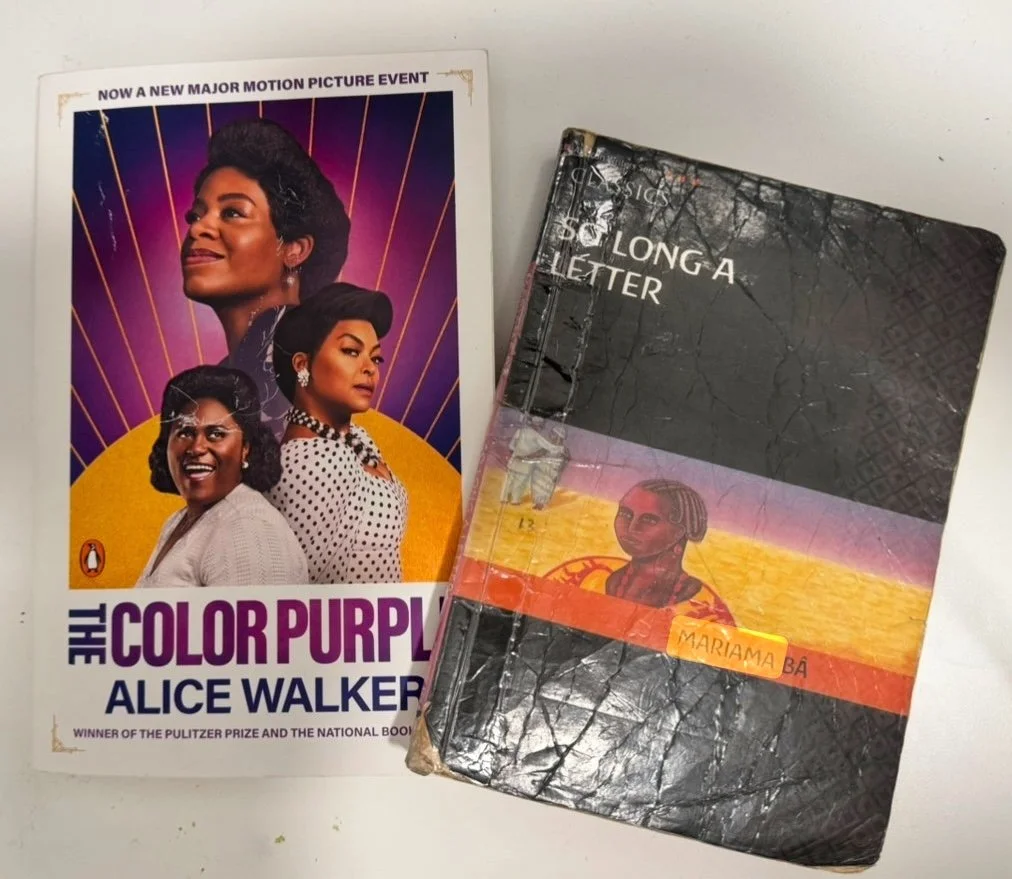

Reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and Mariama Bâ’s So Long a Letter felt like listening to a love song; or a prayer to God; of two women having a conversation across continents. One is from the American South, the other from Senegal, West Africa. Though set in vastly different worlds, both novels tell stories of women navigating pain, betrayal, and societal expectations, while discovering their voices and reclaiming their power in a man’s world.

I first read So Long a Letter in junior secondary school. Despite its brevity: about 88 pages. I’ve returned to it often, each time finding new layers of meaning.

In 2024, I watched The Color Purple on the big screen in Harlem, New York. The film left such a deep impression on me that I rushed home, eager to dive into the novel. I remembered buying the book from a local vendor on Harlem’s bustling 125th Street, near the Apollo Theater. As I turned its pages, I couldn’t help but notice striking similarities between Walker’s and Bâ’s writing styles. Both authors use letters as a storytelling tool, creating an intimate connection with the reader. Celie writes to God and later to her sister Nettie, something most of us do in our loneliest moments, while Ramatoulaye pours her heart into a letter to her dear friend Aissatou. This epistolary style feels personal, like sitting across from a friend, listening as they reveal their deepest fears, hopes, and dreams.

At the heart of both novels are women grappling with oppressive systems. Celie endures years of abuse, silenced by the men who control her life, until she finds the courage to fight back, supported by women like Shug Avery. Ramatoulaye faces the heartbreak of her husband’s betrayal when he takes a second wife; an act permitted by Senegalese culture but one that leaves her emotionally shattered. Her solace comes from the friendship and understanding she shares with Aissatou.

As I read The Color Purple, I found myself wondering: Could So Long a Letter have influenced Alice Walker? After all, Bâ’s novel was published earlier. Out of curiosity, I searched the internet, hoping to find a connection, an interview, an article, anything that might confirm my suspicion. But I was disappointed; I didn’t find any concrete evidence to support the idea. What I learned, however, is that at the heart of literature lies a universal language that resonates with people of all races, whether in Asia, Europe, or Africa. While the experiences of women in Senegal and America may seem different on the surface, they’re rooted in the same systems that try to silence, control, and define women.

In today’s world, where women’s rights continue to be challenged, these stories deserve a place on every bookshelf. They remind us of the struggles faced by Black women, disabled women, Christian women, Muslim women, atheist women, queer women, uneducated women, unemployed women, and even the powerful women who are often expected to bear it all in their silence.

Melvin Sharty is the co-author of "Talking Kapok Tree & Other Short Stories", and author of "A Gift for Failure (a novella). Melvin lives in Harlem, New York where he works for a non-profit. During his free time, he enjoys writing, visiting museums, or playing soccer.

The Art of James Baldwin and Chinua Achebe: A Reflection

During their first meeting at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst in 1980, James Baldwin had described Chinua Achebe’s writing as “a magnificent confirmation of the human experience,” while Achebe praised Baldwin as “a passionate, unflinching, and prophetic writer” who illuminated “the darkest corners of human existence with uncompromising honesty.”

When I think about art, I see it as both a mirror and a tool—on one side, reflecting the world as it is, while on the other, reimagining it as it could be. For Chinua Achebe, art represents “man’s constant effort to create for himself a different order of reality from that which is given to him.” For James Baldwin, art is an unrelenting pursuit, where the artist “must drive to the heart of every answer and expose the question the answer hides.” Reading Baldwin’s If Beale Street Could Talk (1974) and Achebe’s Arrow of God (1964), I was struck by Achebe’s provocative portrayal of art and Baldwin’s investigative depth—how they both understood the issues of their time and defiantly captured the essence of how art shapes and interrogates the human experience.

Art’s ability to interrogate human experience or our reality of being has often provided grounding for those, like myself, caught between worlds. As a nonimmigrant living and working in Harlem, New York City, I have frequently turned to Baldwin’s and Achebe’s works to reconcile my present and find help about writing my own memories of home. For many Africans who leave the continent in search of new beginnings, whether it’s education or job, loneliness and homesickness are like sides of the same coin that draw you on both ends. For me, reading and writing have offered me balance, and a space to tell my truth.

While reading Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), I noticed how he portrays truth as the cornerstone of an artist’s responsibility, a means of personal and societal liberation. As uncompromising and often painful, he viewed truth as “always necessary”. As he wrote, “It’s the artist’s duty to confront and reveal truth, no matter the cost.” Similarly, Achebe placed truth at the heart of his art, which if you read for instance Things Fall Apart (1958), you will notice how Achebe juxtaposed the Igbo traditional beliefs with Christianity without judgement. Truth, for Achebe, was not merely a moral compass by which to justify, but a lens through which to view reality.

When I arrived in Harlem in the winter of 2023, a local historian told me, “A half-truth is a whole lie,” a phrase which has ever since, pushed me to observe Harlem with strikingly familiarity—like Freetown, Accra, or Dakar, where the concrete street life, busty markets, and congested traffic, greet you with passion. Harlem welcomed me, much like Freetown, but I see vividly, a city embracing one of its heroes, in the food, the jazz, the blues, swag, in churches, and books. For Baldwin’s Harlem, preserving truth is a necessity, a calling to represent their heroes and preserve their truths. No wonderI caught myself engulfed in the writings of a man who had rested in power a century ago, and even in exile, Baldwin’s art remained deeply rooted in the struggles, triumphs, and histories of Harlem.

Baldwin left the United States for France in 1948 at the age of 24, escaping the suffocating weight of systemic racism. In The Fire Next Time (1963), he reflected on how Harlem remained with him even in exile, shaping his perspective and art.

Achebe, on the other hand, experienced political exile after the Biafran War, an event that deeply informed his later works, such as Anthills of the Savannah (1987). For both Baldwin and Achebe, exile became a platform for reflection and deep observation—a reconnection to their past. Baldwin needed to escape Harlem to tell its truth; Achebe carried his truth with him across continents. Through their works, both writers served as bridges between their homelands and the broader world.

Another reason I am drawn to Baldwin’s and Achebe’s works is their portrayal of male characters, reflecting the complexities of masculinity, identity, and societal expectations. As someone raised by a single mother, I experienced abandonment at a young age. My father, though a gifted artist, struggled to channel his love for art into love for his children. This tension often makes me question the balance between an artist’s devotion to their craft and their commitment outside of it.

In Baldwin’s Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953), he created a male character; Gabriel, who grappled with guilt and societal oppression. Similarly, in If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), Baldwin’s Fonny, a sculptor, fights for personal liberation in a world dominated by systemic racism.

Achebe’s male characters, like Baldwin’s, face similar struggles. For instance, Okonkwo in Things Fall Apart (1958) is driven by a fear of weakness and failure, shaped by his father’s perceived shortcomings and his inability to stop the emergence of a new religion that threatens to dismantle his world—forces that ultimately contribute to his downfall. Both authors demonstrate how societal forces—racism in Baldwin’s Harlem and colonialism in Achebe’s Nigeria—shape and often destroy their male characters.

Yet, if there is one theme I have continually drawn from their work, it is the persistent need to rewrite my own script—to seek my truth and embrace my responsibility as a writer.

Melvin Sharty is the co-author of "Talking Kapok Tree & Other Short Stories", and author of "A Gift for Failure (a novella). Melvin lives in Harlem, New York where he works for a non-profit. During his free time, he enjoys writing, visiting museums, or playing soccer.

The Hip-Hop Intellectual: A Review of Kao Denero’s ‘Heroes’ Album

Album Review: The Hip-Hop Intellectual: A Review of Kao Denero’s ‘Heroes’ Album

by Paul A. Conteh

Sierra Leonean rapper, Kao Denero, released his album titled "Heroes" early in May 2024. In this 15-track album, the rapper showcases his storytelling skills, lyrical ability, poetic flow, and intellectual maturity.

Within the album, six songs integrate themes of Pan-Africanism, Black Nationalism and Black Consciousness among other things.

In the lead track, Think About It, Kao addresses the African struggle. He incorporates a South African melody into the background music, as South Africa was a significant hub of the black struggle during the Apartheid era. He also connects the African struggle to other countries that were colonized by Western powers. This is why for example, he gave a shout out to Che Guevara.

The songs Sheku and Strasser are a symbolic representation of the Mano River Union in the African narrative. Kao mentions these two names to provide some rationale for military rule, which is something that Western powers publicly oppose but sometimes support clandestinely. Although I disagree with Kao's messaging in those two songs, I have to remind myself that the hook for the Heroes song has a reference line "my heroes", which infers that the two are Kao's personal heroes.

I believe that the track, Coming to America establishes Kao as a skilled storyteller. Here, Kao portrays a character who challenges stereotypical images of poverty, disease and war on the African continent. The song was inspired by the classic movie of the same name featuring Eddie Murphy.

Ghetto Africa deals with common themes of the African struggle like success stories, and opposition to western imperialism. The rapper uses vivid imagery to paint a picture of the typical African struggle. In one of the success stories referenced in the song, he praises Kagame and his efforts to rebuild Rwanda, a country that was once ravaged by war.

Finally, in the album’s titular track, Heroes, Kao pays homage to three influential figures from the black diaspora: Thomas Sankara, a military leader; Steve Biko, an anti-apartheid activist; and Bob Marley, a reggae artist. The song consists of three verses with each dedicated to one of Kao's black heroes. Within each verse, Kao highlights the impact of another black hero who was inspired by or influenced the hero being praised i.e. Thomas Sankara = Captain Traore, Steve Biko = Malcolm X, Bob Marley = 2 Pac etc.

Kao's new project is a return to the original roots of rap, heavily influenced, I believe, by Nas and the Wu-Tang Clan.

For this afro-fusion-infused hip-hop project, Kao Denero worked with six producers: Lord Moe, Mic Junho, Bash Beatz, Dan Kahn, Gideon, and Mad Naija. Additionally, the rapper collaborated with a group of rappers and singers, including K. Man, Shatta Wale, Fine Face, Stex, Street Vibez, and the emerging soul sensation, Keltony.

With an average song length of four minutes, this album can be streamed on Spotify, Audiomack, YouTube, and SoundCloud. It exemplifies classic Kao Denero style in terms of lyrics, storytelling, flow, punchlines, and production.

I am thoroughly impressed with the intellectual depth of the album. Kao just provided a comprehensive history lesson on many of our black heroes in Africa and the black diaspora. Apart from Kagame of Rwanda and Captain Traore of Burkina Faso, most of the black heroes have already passed away. It makes me wonder, who are our new black heroes?

Paul A. Conteh is a lecturer in the Department of Sociology & Social Work at Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. He is also a member of Hip-Hop Ed, a global movement that reimagines the relationship between hip-hop and education. In addition to his work in higher education, Paul is an agribusiness owner, communications consultant, and development professional.

A Story of Transformation: 'The Journey of Turning Scars into Stars - From a Child Soldier to a Humanitarian,' by Ishmeal Charles.

Book Review - 'The Journey of From a Child Soldier to a humanitarian,' Ishmeal Alfred Charles

Reviewed by Josephine Kamara

In 'The Journey of Turning Scars into Stars - From a Child Soldier to a humanitarian,' Ishmeal Alfred Charles offers a touching account of his experience of war, how his childhood was snatched and forcibly recruited as a child soldier and his journey to his life purpose. In this book, he weaved together personal anecdotes, historical reflections, and his philosophical insights about life and humanitarian work. As Charles aptly puts it from one of the rebel commanders, 'Mercy equates to vulnerability,' and this sentiment underscores the harsh ideology that fuelled the wickedness of the rebels during Sierra Leone's 11-year civil war. Through Charles’ lens, we relive these experiences and witness the transformation of scars into stars—a testament to resilience in the face of adversity.

One of the most compelling aspects of this book is its rich portrayal of Sierra Leone's pre- and post-colonial history, the devastating impact of eleven-year civil war and the subsequent challenges of post-war recovery. Charles’ narrative serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of preserving history and telling our own stories. Too often, narratives about African conflicts are shared through a Western-centric lens, foreigners keeping accounts for us and narrating our past. Sierra Leoneans have been telling stories about the war, mostly narrated orally or presented through artistic expression like paintings. However, this memoir, just like Joseph Ben Kaifala’s account on Adamalui: A Survivor’s Journey from Civil Wars in Africa to Life in America and Ishmeal Beah's account on A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, offers a refreshing and authentic perspective that generations after us will use as a reference point to learn about the important events that took place in Sierra Leone.

While the theme of war and brutality permeates the narrative, I found myself yearning for a deeper exploration of the freedom-fighting ideology these young rebels held that fuelled the conflict. The frustration of young students grappling with entrenched corruption and the subsequent exploitation of mineral resources provided a nuanced backdrop to the conflict - this same freedom-fighting narrative is what led the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC) to institute a huge recruitment drive for the military in a bid to end the war. Many young people joined because they wanted to be part of this "New Military Regime" that was going to end the war - at that time, what these young people knew as participation was their involvement in movements that could end the war. These young men who were insufficiently trained became more violent than even the rebels and ended up inflicting some of the greatest atrocities during the war, yet this aspect felt underexplored in this book. Nonetheless, Charles’ first-hand account offers valuable insights of the war through his own lens and its lasting impact on individuals and communities.

I was particularly drawn to the author’s writing style, which skilfully interweaves humour and poetic language. Lines such as 'Stranded in that unforgiving wilderness' and 'The looming specter of death became an uninvited companion' evoke a vivid sense of atmosphere and emotion. I love to play with words so maybe this could be the reason why I appreciate his skilfulness on this area. Additionally, Charles’ reflection on his maternal instinct – referring to these lines, "My maternal instinct strongly conveyed her longing to hear from me, a sentiment any mother will feel when her child is trapped behind enemy lines"

For a male protagonist to describe his 'maternal instinct,' a sentiment typically associated with motherhood, departed from traditional gender norms and adds depth to the portrayal of familial bonds and in my opinion. I am not quite sure if this was the author’s aim, but I feel it challenges societal expectations, prompting me as a reader to reconsider preconceived notions about gender and parenthood or what motherly instinct feels like. There are interesting takes on gender roles especially in the first two chapters, that gave a vivid picture of patriarchal structures and norms - these could have been an interesting theme to explore deeper.

I am particularly drawn to his humble beginnings, as it feels familiar to me. Charles imbues it with a sense of importance and as a young person myself navigating life's uncertainties, I resonated with the struggles and his unwavering determination to pursue his dreams. The questions he asked himself on the 'Turning Scars into Stars' chapter, and how he mustered all his energy to keep his dreams alive even in dark days, captures the essence of a resilient spirit. I believe his offerings here will resonate with readers of all ages.

With regards to the author’s writing style, I love how he worked out the interesting twist of how fate connected his early work back to Kono, the place where, in his words, he was abducted and recruited as a child soldier and into the mining industry. Fate, they say is not mere coincidence, but the workings of destiny and if that is true these occurrences were divinely orchestrated.

'The Journey of Turning Scars into Stars - From a Child Soldier to a humanitarian,' is indeed compelling testament to the resilience of the human spirit. I deeply appreciate Charles’ philosophy of altruism and his commitment to making the world a better place.

The author’s narrative infuses hope into the hopeless, reminding us that light always awaits at the end of the tunnel and urging readers to confront their own adversities and turn their scars into stars. As we are reminded in these lines:

“Each of us possesses a unique story – one of despair and courage, loss and victory, past and present. By harnessing our stories, we can find solutions to ongoing social issues that threaten our happiness.”

Josephine Kamara was a 2023 Poda-Poda Fellow. She is a girls’ rights advocate with 10+ years of experience.

Toys from Africa

Toys from Africa by Melvin Sharty

As kids growing up in Kenema, in the east of Sierra Leone, we loved drawing, creating models of cars, boats, and jets out of paper. To produce a miniature vehicle, we would spend hours trying to understand exactly how the wheels turn, and then recreate it. We would also use pieces of cardboard and glue to make televisions because our parents could not afford one. We would light an oil lamp inside it to light up the paper screen, providing moving shadows. When we made these toys, our parents would scold us. They would even flog us and tell us to stop bringing scraps from the dustbin into the compound. Now I know that what was unique about these childhood inventions is that we were observant and would pay attention to details.

Between childhood and adulthood, those toys, and the inspiration we got from inventing them faded because no one thought anything of it. Our general science classes in schools focused solely on teaching about inventions from the West, miles away from our environment. Nobody paid attention to what was unique about our toys.

***

When I started traveling to the West, I developed a love for visiting museums. So, whenever I travel to a new city for work, school, or vacation, I always make sure to stop by a museum. More than anything else, museums are spaces where I learn, connect, and find inspiration. Now I know that the childhood spirit of wanting to make or create something is still in me.

Recently, I visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York. It was busy with visitors from all around the world having different accents and attires. At the grand entrance, we were greeted by security guards and a sculpture bearing a message about the museum’s mission since its founding in 1869. On the ground floor, I was met with the imposing skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex resting on an elevated platform. It was awe-inspiring to stand before one of the largest creatures to ever roam the Earth, with its massive jaws, fearsome teeth, and tiny arms. I saw parents and their kids playing around it. I too couldn’t resist taking some selfies with the skeleton in the background.

Photo Credit: Melvin Sharty

I then proceeded to the third floor where my inspiration to write this reflection was sparked. Everybody was busy taking pictures or just staring at the magnitude of wonder and creativity in front of them. However, there was one exhibition that didn’t get enough attention, perhaps because it was quite different from all the other exhibitions. I went there immediately.

The exhibition was labelled, “African Ethnography.” To my surprise, it was a collection of toys from Africa made of tins and cans—the same kinds of toys we used to make as kids. “Why are they here?” I wondered. And then, when I read further, I learnt that it was “to show people about the creativity of Africa’s kids.” I giggled. Are these not the same toys we used to make out of scraps as kids? I thought to myself. The exhibits were exact replicas of the toys I had made when I was a kid. Back then, we would use a knife to cut open the milk tin, a stone to flatten it, and with our bare hands, put all parts together to form slippers and various kinds of shapes.

'So silly,” that’s how the adults in our neighborhood would describe us because they didn’t know what our driving force was. They didn’t know that as kids, we were trying to find solutions, we were curious, and wanted to reinvent the world around us.

These toys didn’t inspire our parents, neither were our teachers excited by them, but here they were in one of the world’s most prestigious museums on exhibition for people from all around the world to see. I was amused. As I took some time to see more, I wondered, who gets the benefits out of this? Is it the western world?

***

At the age of twelve, a Sierra Leonean boy named Kevin Doe, taught himself engineering by building his own radio station in Freetown. Doe had also built a generator from scrap metals collected from dustbins in his neighborhood.

Jeremiah Thoronka, at fourteen, invented a device that uses kinetic energy from traffic and pedestrian congestion in Freetown to generate clean power.

Photo Credit: Melvin Sharty

Both innovators now live abroad where they are highly recognized and supported. This supports my point that if we cannot invest in our human capital, the West would come to invest in them and take them away. There are hundreds of examples of Jeremiah, Doe, and even me, kids who are out there in Africa, but would never take their inventions forward because people in their community never believed in them. What we considered as mere toys from Africa are all over the western world in museums, universities, offices, schools, and businesses.

I think that as Africans, we don’t often value what we have within our reach. The fact that I was seeing toys taken out African soil exhibited in the United States made me realize the importance of valuing our own ingenuity and creativity. Too often, we look elsewhere for inspiration or innovation, we overlook the treasures that are right in front of us, whether it’s in our communities, our forests, or our backyards. We rebuke our kids from playing or making things or asking questions. We criticize ourselves for trying new ideas. We are satisfied with old ways of thinking and doing.

We must start paying attention to the talents of our children, our youth, and our adults. Only then can we truly tap into the human capital of every person and realize the richness that surrounds us.

Africans- invest, support, and build your toys so the world would buy.

Melvin Sharty is the co-author of "Talking Kapok Tree & Other Short Stories", and author of "A Gift for Failure (a novella). Melvin lives in Harlem, New York where he works for a non-profit. During his free time, he enjoys writing, visiting museums, or playing soccer.

Yema Lucilda Hunter’s Road To Freedom: A Family and National Tell-Tale

Yema Lucilda Hunter’s Road to Freedom ( later republished as Seeking Freedom)* retells the story of the foundation and existence of the settler community in Sierra Leone. Considered her magnum opus, Hunter’s novel weaves the subtleties and realities of a migrant family into the descending air of characters’ search for identity. In the book, the Dixon family’s holy grail seemed eternally evasive and invariably unreachable, for what comes across as a benefit for a devout Christian family was the grant of a royal permit to freedom. Their liberty, ironically, cannot be shoehorned to a higher God, but tied to the scruff of a superior nation, the King’s United Kingdom. When Steinbeck highlighted America’s Dust Bowl condition in his celebratory treatise, The Grapes of Wrath, the writing of flight fiction and escapist literature blossomed to the global literary scene, permeating communities where oppression and repression forced families and individuals to flee their homes in search of greener pastures.

On a cross-continental scale, the equivalence of this is Road To Freedom as a family in silence and [in growth] yearn for their personal liberty which has been mortgaged on the hearthstone of politics and feud. Properly conceived of as historical fiction, the novel has at its core, the universal themes of quest for freedom, clash of cultures and identity crisis. Hunter presents a nuclear Nova Scotian family whose latter years would be spent in Freetown, Sierra Leone, as a settler group. They would be confronted with the harsh vagaries of a new land to wit, animosity from natives, inclement weather, lack of funds for survival, and struggle for an identifiable governance structure. Before that, they would have to bear the brunt of a neglected social contract etched between their forefathers and Great Britain—the well-known promise from Britain to formerly enslaved Africans who fought on their side in the venturesome American War of Independence. Their freedom was a drum roll, clipped by the ribbons of Her Imperial Majesty, and tethered to the uncompromising discretion of the British government.

The fictional figurehead character Brother Thomas Peters is a real personality whose contribution to the establishment of Freetown is as immeasurable and profound as his character role in the novel. He is the saviour of the Dixons and other freedom-hungry families in the novel whose unceasing vespers seek the benevolence of God in guiding his journey to England. Without any doubt, Hunter has elevated this side of Sierra Leone’s history to the reader’s sixth sense—instead of the dry and wry sale of historical accounts by historians, an emotional and cathartic flair has been laced into the story’s style and language. England-bound, Thomas Peter’s sojourn is presented in an enlivened episode; occasioning a frenetic outpour of wishes of good fortune, prayers for safe reach, and splenetic farewells from the aging to the aged. Suffice to say that the author’s willed desire to present such situations dovetails with our thirst for unbridled freedom, glorying in our environment where we can relate with society unrestrained. From economic independence to political autonomy, we will not balk at any chance that comes with such reprisals. The events are old, but the relevance must be told and rung in the minds of succeeding generations that revolutions and wars are imminent should our freedom be continuously seized; this, to the very least, is part of the author’s purpose in knitting this timeless revelation together.

Hunter’s motifs help parboil the exposure of her underlying messages. Death, broken promises, failed marriages, power struggle and prayers are the novel’s recurring issues which unfailingly culminate in its overall message, that freedom is exaggerated. Mankind, God’s insatiable being, is always on the move for more. Freetown was established in the late 18th century as a haven for liberated Africans, founded based on Christianity and carved on the path of Westernisation. Hunter leaves no stone unturned in rewriting this checkered history of a great nation through the perspective of the Dixon family who are subject of the vicissitudes of daily life in a new world. The author is adept at moulding into a literary block, the early developments which unsettled the Province of Freedom: from the struggle for land, the issue of quit rent, the uncertainty of company rule, sporadic immigrant rebellion, to British takeover and disruption of the administrative and legislative autonomy which was once the domain of local leaders in the settler community.

One would not chuckle at the writer’s language and characterisation. There are no conspicuously invidious characters who will make the reader wince; neither are there dominating characters who will eel the reader toward them by disregarding the other relevant bits and pieces of the story. Told from the first-person narrative, the facts of the story can seem manipulated by the narrator-cum-character Deanie Dixon. Whether the narration is exaggerated or not is a deliberate attempt by the author to compete with historians and political scientists who think and say a thing or two about the history of Sierra Leone.

In a nutshell, Yeama Lucilda Hunter, a Sierra Leonean of Afro-Caribbean descent, presents a realistic portraiture of a people flickering between distress and momentary delight in a new country.

*Editor’s note: Road to Freedom was later republished as Seeking Freedom. The book is now both known as Road to Freedom and Seeking Freedom.

Sulaiman Bonnie is a 2023 fellow at Poa-Poda Stories. He is a writer, law student and teacher. He lives in Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Adventures of an Awkward African Kid - The Fire

Written from the point of view of a young boy from the east end of Freetown who details personal and family life experiences amidst one of the most brutal civil wars on the African continent.

It was no secret that Grandma was particularly fond of her youngest grandchild, which happens to be me. Everywhere Grandma went, I went along. I was nicknamed Grandma's “walking stick” to my displeasure. However, I did enjoy the perks of being a ‘lastina’: she always had my back.

As I transitioned into a teenager, my interests turned to girls and hanging out with my friends. And because I wanted to be able to defend my future girlfriend like I had seen in The Karate Kid movie, I enlisted our neighbour to train me. My plan backfired one Saturday afternoon when my Uncle caught me taking karate lessons. I was punished intently to deter my participation. The greatest irony is that I was being beaten because “Kung Fu” was deemed physically exhausting and could lead to a medical crisis. Pfft, it was as if they thought the good old authentic African “discipline” meted to me, was somehow physically replenishing. Needless to say, I had no guts, liver or gall to voice out that thought because my parents just didn’t play like that.

With the absence of karate training, I sought comfort in the thoughts of spending quality time with my crush. She was a beautiful girl, tall with a skinny frame and a smile that instantly made me feel warm and fuzzy in my belly. She had a low haircut, was a little bit bossy, had a bubbly personality and a slight gap tooth causing her to pronounce certain words with a cute lisp.

Since we had once danced to more than three songs at her cousin’s birthday, and because her cousin was one of my close friends, it was virtually a done deal that she would be my girlfriend. I just needed to find the right moment to ask her out and make it official.

***

The first Monday morning in January of 1999, businesses in Freetown city came alive after the usual festivities and fun-packed Christmas celebrations. Kissy Street, now Sani Abacha Street, was laced with the aroma of hot black coffee and freshly-baked ‘Fula’ bread.

On the first day of school, I was excited to hop on a Poda Poda with my friends at Garrison Street. While we lived in the East end, our school was bound West in Murray Town. I met with my friend Royston who always seemed to have the whitest shirt even after running through a notoriously red dirt area called ‘red pump’; Kofi was a video game junkie like me and also a budding footballer; and then there was Macfoy and the other boys from the east with whom we joked and laughed all the way while sharing incredible accounts of our holiday experiences.

We were filled with much euphoria as we became reunited with our mates. Some left for the holidays as boys and returned as men. Thankfully, I was still a boy. But not for much longer.

The first day of school ended almost as quickly as the holidays had flashed past. We skipped the last period and took the slum bay route of the city to get home. We used our transport fare to purchase snacks and treats while teasing and bantering with each other on the way. I returned home thoroughly exhausted, finishing my late lunch without any fuss. I showered and went straight to bed. The next day would be grandma’s 80th birthday and it was certainly going to be a good day.

Then came the morning of Tuesday the 6th which was ushered in by gunfire.

My family and all residents of the East of Freetown were greeted by fleeing crowds with their loads. Then there was a short lull of silence, followed by rapid gunshots, RPG bursts and the overpowering smell of tear gas & ordinances. The long senseless civil war of eight years had been building up to a climax, with rebel forces now storming the capital city for their bloodiest quest: “Operation No Living Thing”.

Tuning to the national radio stations for information was pointless, all they played on repeat were Buju Banton reggae songs and Canterbury Cathedral renditions of the Psalms of David. There had been warnings of a planned invasion of Freetown but somehow the security forces slept on the intel. Or did they? The official instruction on the radio was for residents to remain indoors.

At the time, I had experienced the coups of NPRC 1 & 2, AFRC, and the ECOMOG intervention of 1998 in which Nigerian-led troops crawled in through waste gutters to liberate us so I naively expected the best outcome.

And while I dreaded any harm befalling me or my family, my most pressing concern was my childhood crush on the other side of the city. Was she safe? How would this "rebel thing" affect our big date at Aqua Sports Club on Saturday? The landline phones had been shot down and this being the era just before the smartphone and social media, there was no other way to know.

On Wednesday, the second day of the siege, a bomb landed on the house across the road from our family home. The house next to it belonged to the Jarrets’ which also went up in flames. Like a symphonic domino knockdown, a gentle harmattan breeze lifted the flames across the road and set the tip of our roof ablaze.

At the time, our house was a fifty-year-old wooden structure which had been renovated right before the holidays complete with a fresh lick of paint but that did not save it from going up in flames like a crispy bonfire on a breezy evening. Neighbours with ancient grudges laughed at our misfortune as our house was transformed into cinders. But as it is said proverbially in Krio “the rain does not only fall on an individual doorstep.” Moments later the same wind floated the flames over to their structure.

The smoke was worse than grandma’s wood-smoked jollof cooking on Christmas day. The hardest decision for us was deciding what to take and what to leave for the raging inferno. The fire started around 1:30 p.m. and by sunset, it had ended its wicked scheme. A block of five houses and churches had been raised to the ground.

That night, my family huddled in the back kitchen/coal storeroom/de-factor chicken shed. I realized then that there was no going back. Things would simply never be the same again. Despite the loss of centuries' worth of the family’s heirlooms and personal belongings, the lives of my loved ones were surely the most important treasures we still had. The value of life was irrevocably imprinted in my young mind.

At random intervals, my mind would race back to my Sega Mega Drive games console, the "LA Gear” trainers with flashing lights, and my red photo album which contained cherished memories of good times with friends, family, and most importantly the pics of my crush and I cutting the cake at my thirteenth birthday party.

These blissful reminiscences were often rudely interrupted by sporadic machine gunfire. The pro-government forces and the rebels continued the scattered fighting often with airstrike support from the ECOMOG jets. Radio Democracy 98.1 had been relocated outside of the city to Lungi and was providing pro-government news and updates including broadcasts of BBC’s Focus On Africa. Several people were killed when they came out to the streets believing wrong info from the government radio station, they were sadly ambushed and killed by the rebel forces. We didn’t know what and who to believe.

Who knew that our burnt-down home would turn out to be a blessing in disguise? The rebels assumed our compound had been deserted and this dissuaded them from ever breaching the perimeter.

The battle raged on for nearly a fortnight. With our home located in the east, on the main entry road to the city, it was implausible for our family of seven; a grandparent, a dad and a mom accompanied by four minors; to safely cross nearly 20 km of city terrain loaded with snipers, Nigerian bomber jets playing cops and robbers. We didn’t fancy being converted to human shields for either side so we were forced to wait it out behind enemy lines.

***

Mom had given me a cassette player as a gift for passing my secondary school entrance exams. Pre-invasion, music had been my escape. I’d listen to all sorts of sounds and get lost in them. My playlist was eclectic, with songs from Penny Penny, Michael Jackson, Angelique Kidjo, Peter Andre etc. Fused with electric Euro Dance sounds from Ace of Base, Vengaboys, Black Box, Robyn, Snap, etc.

Over the holidays I made a tape with handpicked music for my crush. It was a mixtape before I knew what a mixtape was. I dubbed songs from Janet Jackson, Mary J. Blige, Backstreet Boys, Brandy, Keith Sweat, Backstreet, Will Smith, and Celine Dion and titled it “The Love Tape”. During the fire, the mini-cassette player and my entire music collection were incinerated. On those sad nights behind enemy lines, I would perform many of those songs to myself, mostly in my head to escape the dreadful reality around me. Usually, I would be accompanied by a call and response of gunfire in the background.

After what felt like countless days of terror, the siege ended almost as unexpectedly as it had started. In the days leading up to D-day, there had been propaganda reports from both pro and anti-government forces that each was making gains on the other.

That particular afternoon after much intense fighting, it became eerily silent.

Behind enemy lines, one quickly learns how to identify the sounds of the different weapons. The rebels were more reckless and sporadic in their shooting while mostly clusters and bursts of shots came from pro-government forces.

There had been heavy rebel gunfire and then a lull till early evening.

We then heard pro-government soldiers doing a door-to-door sweep. The overwhelming smell of smoke, burnt flesh and destruction around us dominated our senses. We had no energy to celebrate other than breathe weary sighs of relief.

At dawn, Grandma’s eldest son accompanied by his son arrived to rescue us.

As we pulled off from our burnt-out bunker, no one said a word, but it was clear that we were all thinking the same thing.

Driving through the city littered with half-decomposed corpses strewn with jubilant feasting vultures, burning cars, and shelled-out buildings was all too surreal for my senses. They looked like scenes my older brother and I had seen of the Vietnam War in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket film. The once-ancient megalith of our city had been practically razed to the ground.

What happens after everything falls apart?

Days turned into weeks and weeks into months and then we were picking up the pieces.

***

Our school reopened in May, this time, the reunion of us boys was sombre. Our boyish excitement had been replaced by something else, it was as though we had all become men for all the wrong reasons: we had seen things.

The saddest part remains that I never actually got to go on that date with my crush.

Grandma relocated to London and as her ‘walking stick’, I followed suit. With that, I was also involuntarily removed from my crush, my friends and my social life in Freetown. I told my sweetheart I would be back soon, but I never knew that “soon” would be twelve years. These are some of the things we lost in the fire, which became an intricate set-up for the next chapter of my life.

*Author’s note: This is a work of nonfiction. Names of individuals have been altered for privacy.

Nick Asgill is a Creative content producer with a passion for developing African culture stories and youth talent in Africa and the Diaspora entertainment spaces. Born and raised in Sierra Leone, Nick found his way into the entertainment industry in London through the “Prince's Trust” Urban Voices program and was mentored by Nigerian entertainment trailblazer JJC Skillz. Nick holds a Bachelor degree in Media Production and has won awards in related fields.

Joining the Conversation: A Review of David Moinina Sengeh’s Radical Inclusion

Radical Inclusion is a debut work of nonfiction by David Moinina Sengeh, the Minister of Basic and Senior Secondary School Education in Sierra Leone. Published in May 2023, the book joins Melinda French Gates’ book, The Moment of Lift (2019) in a book series of the same title that was created by Gates. As a contribution to the series, Sengeh’s Radical Inclusion embodies the Moment of Lift Books' mission of “publishing original nonfiction […] to unlock a more equal world for women and girls.”

The book centers the story of how newly appointed as a cabinet minister in Sierra Leone in 2019, Sengeh sought to overturn the ban on pregnant girls from attending school across the country. In his quest, the stakes are high primarily because many citizens view his proposal to be too liberal, foreign, and against the grain of religion and tradition in Sierra Leone. Sengeh writes about his concern that people he once thought to be like-minded and progressive express sentiments that exclude pregnant and vulnerable girls. This strengthens his commitment to uphold their ‘Radical Inclusion in Schools’ policy that strives for the “the intentional inclusion (…) of historically marginalized groups: pregnant girls and parent learners, children with disabilities, children from rural and underserved areas, and children from low-income families.” (179).

Radical Inclusion doubles as a how-to book via its provision of seven steps termed “the Seven Principles of Radical Inclusion”. These steps are discussed in separate chapters where Sengeh details some life ‘lessons in exclusion’ and exemplifies how he achieves success with uplifting the ban. The seven practical steps range from pointers like the identification of exclusion or injustice, active listening, coalition building, etc. in a bid to experience positive change of varying magnitudes.

Non-fiction books like this present a unique challenge of balancing timelines, anecdotes, advice, and musings. Sengeh achieves a good balance with a fast-paced and measured narrative tone with which the reader becomes acquainted with his outlook and beliefs. In 240 pages, we are introduced to Sengeh, the doting father of three girls, the Harvard and MIT-educated young man turned minister and the rap and colourful sock aficionado among other things.

In his narration, Sengeh also uses certain imagery that emphasize his empathy like the details of a conversation with a pregnant young woman by a well that moves him to tears or when he engages in active listening with naysayers in opposition to his proposal to lift the ban. Most chapters engage with book quotes from writers and iconic leaders like Brené Brown, Shimon Peres, and Barack Obama or tips gleaned from conversations with Tanzania’s Jakaya Kikwete. Radical Inclusion is therefore cleverly written with attention to persuasive elements that make for good writing.

Perhaps most apparent is the book's overt use of context cues and definition of terms which signals that the intended audience is primarily Western or American. Some examples are defining terms like code-switching, and Salone time, or commenting on ‘football versus soccer’ and in other instances, offering direct translations of phrases in Krio to English. What makes this effective is the inclusion of quotes by world leaders, and anecdotes detailing Sengeh’s experiences both abroad and at home in Sierra Leone thus rendering the book one of global relevance.

The success of Radical Inclusion reaffirms that Sengeh is a fitting individual to have authored it. Through the book, he presents himself as someone who embodies radical inclusion and empathy both in the workplace and at home. The book is also successful in the way it accomplishes the discussion of radical inclusion via seven principles and its portrayal of Sengeh as a progressive leader. The call to action is clear. It is that we join the conversation; steer away from actions of exclusion; and think and practice inclusion. And when we do, there are seven well-crafted steps and principles to guide us.

Charmaine Denison-George is an associate editor at Poda-Poda Stories

The Power of Love, not the Love of Power

An Ode to “I Picked Up My Pen” by the Late Henry Olufumi Macauley Sr

by Cheukai Songhai Makari

“When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace”

- Jimi Hendrix

The last week of 61. Another difficult year. It is becoming more and more frequent as there seems to be less to be happy about in Sierra Leone with each passing year. After avoiding visiting her for a year I don't know what I expected when I returned home two weeks ago, but the stagnancy, despair and undeniable feeling of discontent has been palpable. I feel guilty because at least I have the opportunity to take breaks from witnessing the deterioration of the land that we love in real time while the disgruntlement is evident in the faces of the people experiencing it everyday.

Each year, the lights get dimmer, the smiles less joyful, the stomachs more hungry and the streets more silent. But to me the silence isn't a peaceful one, it's the rumblings of frustrated people that are reaching their boiling point. It’s the calm before the storm.

Although it's a thought that pains me to actualize through putting pen to paper, I can’t shake the feeling that the storm is inevitable unless we start making decisions that are driven by power of love rather than the love of power. This love for everything besides the people and the country we reside in is the trait that is being passed down to generations, limiting the transformation of what could be possible in this country and the change we are able to see in our lifetime. Even as I write this, the change that I believed to be possible last year has shifted as I consider the culture surrounding civic duty and leadership is being promoted, passed down and idolised.

We’ve seen it happen before and while people think that the trauma inflicted on our country was enough to set us on the right path, suffering can be a blinding force.

For the past 61 years we have been passing on the baton of selfish decisions limited to what we can achieve in our lifetime. For a people that claim this is the land that we love, it's always a surprise to see the actions we take reflecting anything but that. As we head into another democratic election since the independence of this great nation I only hope that we can remember the passion and faith our parents once had, and the discouragement they feel only to see Sierra Leone as it is today and allow that to fuel us to ensure that it won’t be our same fate. Entering chapter 62 today, I only hope we can begin to see our country as the extension of ourselves so that when we decide to act in our best interest, it's in the interest of our country the citizens that deserve to enjoy the greatness that this nation has to offer. Another year older means another year wiser and we can to push the needle so that the change that we idealise in Sierra Leone can be something that is considered achievable, even if not in our lifetime at least in the lifetime of those who we pass the baton to.

Looking past 62 doesn't seem as clear or optimistic as it should be, but for today, happiest bittersweet birthday Mama Salone.

Cheukai Songhai Makari is a young passionate Sierra Leonean based in New York City. She was raised in Freetown and is pursuing a career in economic development with a drive to increase the standard of lvinng for the average Sierra Leonean.

Chasing Freedom

Photo Credits: Sama Kai

By Bassie Bondeva Turay

In February 2023, I left Sierra Leone for a youth leadership program in the United States with a colleague, a young woman with whom I’d formed a bond learning Temne. Three weeks later, I was on my own on our return flight to Freetown. The young woman, who had only just started college in Sierra Leone, absconded from the program in our second week to remain in the United States. I know it wasn’t an easy decision for her to make, to be undocumented in a country that is alien to her. During our trip, she shared personal stories of hurt and struggle growing up in rural Sierra Leone in a single-parent household. Hers was a life of many challenges, and she felt that America would free her from them.

I have resisted the urge to pass harsh judgment on her because I recognize my own privileges which have protected me from taking such a path. I grew up in Freetown where I attended private schools, studied abroad, and have been opportune to navigate influential spaces. But I’ve learnt that even in those circles with young people who have access to power and affluence, their motivation is also to chase freedom elsewhere. Sometimes I wonder that if everyone is so bent on leaving Sierra Leone, why am I fixated on experiencing life in all its ‘glory’ here?

Last year, when I told a friend that I was returning home after completing my graduate studies abroad, he asked, "What are you going to do there?". He was concerned. I may have well told him that I’d packed my bags for hell. But it moved me to unpack the question. It caused me great apprehension to realise that for the first time in almost a decade, I would live in Sierra Leone, and not just engage with it on social media or as a December holidaymaker, yet within myself I could not find an answer to my friend’s question. Nonetheless, I returned and what I have noticed in my few months at home is not so different from what I felt while I was away. The fact remains that the future is gloomy for our country, that many of our citizens, particularly our youth, are unhappy. It seems to me that the country is on auto-pilot mode, amid a divisive political climate, worsening economic conditions, and fractured social cohesion.

I sense fear from different sides of our society, our government sees dissent as dangerous because of political pundits who present inflammatory speech to the public. On the other hand, opposition leaders are wary of a government that they believe is removed from the reality of mass hunger and other dissatisfactions. These fears are not new, they are primal. They would be the same whether you switched the roles that the green or the red currently hold. It is the outcome of years of simmering suspicion in the ways that different actors in our ethno-regional system have misgoverned the country. These fears are worsened by rife misinformation on social media, feeding flames of distrust. This may have been a factor in the August 10th incident in 2022, or maybe there’s just something in the water in Sierra Leone. Whatever you believe the cause of that day was, our parents understand. For them, it is a mirror of the past. Following a long period of misrule, young people were left in such misery that it was easy for them to band together in a ragtag way and inflict mayhem on their communities. But the majority of today's young people have no recollection of the events that led us to this precarious situation and are trapped in a mire.

Young Sierra Leoneans are particularly vulnerable, lagging behind our global counterparts, and far from receiving the quality of life we deserve. Of course, this is not something that is only just happening now. Under the previous regime, The Guardian named Sierra Leone “the most dangerous place in the world to be a young person”, citing WHO data. Frankly not much has changed; access to quality education and healthcare remains poor, substance abuse is rife - young men nodding off in the streets is now commonplace, jobs are still scarce, and every young person dreams of a Canadian, American, or British passport. I won’t say which one I prefer but it is this frustration that influences young Sierra Leoneans to fight or fly.

During my undergraduate years at the University of Rochester, we had a strong mental health program with a catchphrase that could be seen on posters in practically every dorm, hallway, or classroom: DON'T IGNORE THE SIGNS. It was meant to inform students to pay attention to any unusual changes in the behaviour or appearance of their colleagues. The signs were often precursors of an underlying problem. It was wise for us to take note of them so we could nip a looming disaster in the bud. I am aware of the ‘signs’ in Sierra Leone today, which is why I have written this essay. I am no prophet of doom.

I am aware of a revolutionary surge of young Sierra Leoneans making an impact in their communities, and across sectors, from politics and business to the creative arts and academia. I work closely with adolescents at my local church and my alma mater. My interactions with these young minds have revealed a genuine love for our country, an enthusiasm for change, and a desire to live a good life here.

There is something in the water here, and young Sierra Leoneans should positively ride the wave. I firmly believe that what we need in Sierra Leone is collective action, a movement that completely disrupts the status quo that is divisively ethno-regional, classist, and patriarchal. And if any of us has half the hope that a youthquake will occur here, we must search within to figure out what our role is. Assuming your role requires a great deal of self-discipline and character development; you must first lead yourself exemplarily before enabling others.

Philippians 2:4 instructs us to “consider not only our own interests but also the interests of others”. While 1 Peter 4:10 admonishes us to “use the abilities that God has given us to serve others”. Young Sierra Leoneans must start moving curiously towards collaboration, rather than working in silos to create more meaningful and inclusive environments for their target audience. Let’s seek out those who share our passions and interests and begin to talk about starting some ideas together. Ultimately, a culture of collaborative action based on our shared priorities would develop into the foundation for the socio-political change we need. Our deliberate alliances, which are effective in resolving the challenges we face across sectors, will result in a formidable force that will eventually grow into a radically progressive and inclusive movement at all levels in Sierra Leone.

On the occasion of my undergraduate graduation, a Sierra Leonean woman,who is a role model to me, sent a note that has since had a profound impact on me. She hoped that my path would lead back to Sierra Leone. I began passing on this wish to other young people who have the potential to positively influence Sierra Leone but are unsure how to take on that responsibility and would rather just disconnect. So, when I finally accepted the Sierra Leonean sister's departure from our leadership program in the U.S., I did what I knew best. I prayed for her safety and hoped that whatever path she takes, it would bring her back to Sierra Leone.

Bassie Bondeva Turay is deeply committed to youth empowerment, education, and leadership development. He is a BCA Leadership Fellow and a Management Consultant for CTI Consulting Ltd. Bassie is also a Children's Sunday School instructor and Youth Adviser at the Bishop Baughman Memorial United Methodist Church, as well as a teacher of Government and History at the Sierra Leone Grammar School.

Photo Credits: Sama Kai

Freetown's Dreamers

Unu mek wi shek smɔl. Di poda poda de fɔs i tayt.

1787 was the year emancipated slaves arrived in the Province of Freedom, later named Freetown. They came to a land that promised to bring their dreams of freedom and ownership to fruition. A century later, Africans from all over the continent came to fulfill their dreams by pursuing an education at Freetown’s Fourah Bay College, nicknamed the Athens of West Africa; Merchants also arrived at Freetown’s shores with dreams of becoming wealthier. Years later, the city has evolved into a smorgasbord of cultures, and is still home to dream chasers.

Legendary Sierra Leonean Musician and political commentator, Daddy Saj, circa 2006 declared his dream on the song ‘Sorriest Part’. Saj envisioned a Sierra Leone where the basic amenities are available to every citizen; a country that caters for its citizens; a state that upholds the rule of law. But almost two decades after releasing ‘Sorriest Part’, this vision remains a figment of a creative mind. Walking through the streets of Freetown, one realizes that Saj may never see his dream come true, but his vision is reimagined and pursued by young Sierra Leonean creators.

Aprɛntis a beg tɛl yu drayva se if i nɔ ple Salon myuzik, wi nɔ de go.

In his debut offering, Game Time, Prodigy Sim uses his exceptional storytelling to share his version of events on ‘The City’ while airing the life and perils of many creators in Freetown. The toils of getting an education (or a backup plan) while pursuing your passion or ideas

"So ar begin write

A few lines down every night

Even though exams was in sight"

And the possibility of making it big weighing against the loneliness experienced by the dream chasers

"In the city where anything can happen

Where you're left alone like a bachelor"

Prodigy Sim, via the same song, shares his dream of being self-employed, an entrepreneur. Honestly, it is a dream many creators share but only few attain for a plethora of reasons, and fear of failure tops this list; the irony right?

"Scared to fail now my biggest - FEAR

Scared to chase my dreams cause I - FEAR"

Freetown remains a symbol of hope. However, its streets are littered with dreams shackled by fear. It may be the fear of failure, inconvenience etc. In his project, Land of Magic, Kadrick dedicates a track to exploring fear. He illuminates his doubts, angst and the uneasiness that comes with being a Sierra Leonean creator.

“I swear sometimes I wonder if

A world where dreams come true can really exist

I can't even ponder it”

Being a creator in an underdeveloped country means lack of tools, limited access to mediums or platforms to share your ideas, limited opportunities for remuneration and other hurdles that come with underdevelopment. These realities have hindered some, but they have also inspired others to create phenomenal art.

“This is for the dreamers with insomnia”

The paradox of pursuing dreams is sleepless nights. In his debut project, If I'm Allowed to Dream, Jjoe Saymah raps of the allure of being a rapper while illustrating the castigation that many young creators in Freetown have to live with. Saymah knows these hurdles too well; from his parents’ desire of him getting a white-collar job, to the depression that often comes with creating.

“Imma put in the work

Dey hustle lek two four seven

Get too much potential for lef untapped"

Freetown is filled with potential; potential hit makers, potential legends, and potential entrepreneurs. But, in a system that does not cater for creators, the lagoon of potential is where most creators languish. Jjoe recognizes this and declares his intention of not remaining untapped; he also challenges other creators to “put in the work”.

Centuries after the first emancipated slaves arrived, the dream may have evolved, but it is still driven by the desire for ownership and to live a better life. To achieve this dream the onus rests upon creators to remain consistent in excellence and build structures that foster ingenuity and longevity.

Long Live the Dream Chasers.

Drayva as yu tek di kɔv, lɛf mi na da jɔnkshɔn.

Marco Koroma is a freelance writer and content creator based in Freetown. He blogs regularly at afrikandude.wordpress.com . He is also the Co-Creator and Curator of Tok U Tok , an open mic and live music event in Freetown.

THE HOMILY OF HOSTILITY AND HOPE BY A HIP-HOP INTELLECTUAL (CORONA VIRUS PANDEMIC)

First, Europeans invaded our land. They captured us as slaves, exploited our resources, eroded our culture, and instituted a colonial system of governance. After independence from the United Kingdom, we thought our chance to build a better society was here. Sadly, those dreams were shattered by a barbaric dictatorship. Next, we suffered civil war for ten years. Later, an Ebola outbreak ravaged our country. This killer disease consumed lives, lines and legacies. To our greatest surprise, the twin disaster was on its way. The mudslide and flooding of August 2017 perished households around the water catchment area of Mount Sugar Loaf. It took us back to square one. With this background, you wonder if life is worth living (for the ordinary Sierra Leonean), as Tupac blasted himself in the song Changes.

The Sierra Leone story has segments of sadness. Ice Cube clearly stated in the rap biopic, Straight Outta Compton - “our arts is a reflection of our reality”. The history of Sierra Leone is shaped around these ugly realities. This is something we as a people cannot erase, but just live with. Amid these harsh realities, we have constantly shown response, reaction, and resiliency.

Fast forward – President Bio declared 2020 as “the year of delivery” from his government. This statement by President Bio is parallel to J.Cole’s poetic genius in Middle Child. He has chanted this policy statement in public gatherings and cabinet meetings. We as citizens watch in anticipation for the goodies of greatness to come down us falling. Well, here we go! The global Corona virus pandemic is threatening to stall development drives. The signs of hostility from this satanic pathogen are visible in Mama Salone. One is left to ponder on this question from Black Eyed Peas “what is wrong with the world, mama?”.

The rulers of Mama Salone have asked us to practice individualism; they have stopped the flying of planes on our air space; they have placed a temporal pause on the houses where the teachings from the Christ and Holy Prophet are studied and they have given closure date to the campuses of the Athens of West Africa. The spots that provide food, family-time, fashion shows, and fantasy clusters have been slammed with indefinite measures. The good news - people are complying with these trends. Even with this positive vibe - “dis tin don really monah wi oh”, as Kao Denero rapped fifteen years ago.

Walk down the streets of Freetown, and you will feel the impact of this horrible outbreak. The prices of commodities are heading sky high; the free flow of information is distorted by corona cry; the bonding religion offers is ceased, and people are losing jobs like the wind. The banks and bureaus have seen a drop in money transfer into Sierra Leone. The western world is on lockdown! The people who send money into Sierra Leone cannot leave their houses, cannot go to work, cannot make additional income, and are saving for any eventual economic catastrophe…”And the struggles of the brothers and the folks”, as rapper Common, expressed in The People.

Kendrick Lamar shared his story in “I” soundtrack. He went through his struggles, trials, and tribulations. But he knew God is going to sail him. In the case of Sierra Leone, we are going to resist this plague. The other countries will defeat this viral venom. And the planet is going to return to the pathway of prosperity. Twista gave us great words of encouragement in Hopeful. The fortunes of this country would change from Jazzy to Jay-Z. The former was this young kid from Brooklyn selling dope. The latter is a billion-dollar worth, Grammy award-winning rapper.

At the end of the day, we are going to join The Game, Tyga, Wiz Khalifa, Lil Wayne & Chris Brown for a celebration. Right now, we need to heed to the advice of Nas - stay Sabali (stay patient).

Paul A. Conteh is a Sierra Leonean Lecturer, Development Professional and Public Affairs Analyst

Dear Woman, Be a Whole Woman.

This is presumably an unrealistic advice to give a group of 27 young women from different countries on Friday 24th July, 2015 during a session of self-reflection at a leadership program in Ghana. But it is sound advice. Something I heed to date.

That day , I penned down what being a whole woman meant for me after a moment of soul searching and reflection. Later reading what I wrote down - a whole woman is a person who is comfortable with who she is and gives out her best no matter what, is honest with herself and loves unconditionally - a part of me agrees. The optimist and romantic in me agrees. But then there's reality.

How can I show up and give my best when I am still fighting to be comfortable in my own weird shoes? Maybe I should first learn the dynamics of contemporary womanhood? Deciphering what womanhood means is complicated. Even more so growing up in a patriarchal society such as ours.

The barriers as an African woman that I face while trying to find out what it means to be a woman; the cultural expectations, stereotypes, figuring out how to balance work, family and friends and still find time for myself. It gets tiring. And then there's the battle within, to know myself, my goals, my values, my passion and what fuels it.

The fact that the playing field is not level in our patriarchal society is infuriating, the ignorance of most men is heart wrenching and then society's frustrations threatens to bring out the "angry black woman". Another stereotype. It is okay to be angry. It is an emotion. It is also understandable since as women we face, struggle with and work hard to transcend the limits society sets for us.

Ignorant comments about body weight, saggy boobs, stretch marks and the vagina, make women feel self- conscious about our bodies. Women have to explain and educate men about our bodies, our needs and continued survival just to bridge the gap of male ignorance.

As a country we have accepted negative aspects of the patriarchal system as something unchangeable. We have a very poor attitude to issues affecting women like teenage pregnancy, child marriage, gender based violence; including intimate partner violence, female genital mutilation, rape, trafficking, sexual abuse. We must dispel certain notions including but not limited to the notion that there are “just” causes for gender based violence, the notion that men have the right to control their wives behavior and “discipline” them, blaming the victim for the violence received.

In Sierra Leone, the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2016 shows that a higher percentage of women as compared to men think domestic violence is justifiable. 86.1% of the women between ages 15-49 have undergone any form of FGM. 36.1% of the women aged 20-49 were married before age 18. https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/sierra_leone_mics6_2017_report.pdf

I see myself as a feminist. Sometimes though, I ponder about what makes me a feminist especially since I sometimes feel I'm a hypocrite. Impostor syndrome hits hard. Should I alienate my values, views, choices? Can I be a feminist and still be a huge fan of Eminem, .a huge fan of rap music? Or do I just fall on my volunteer work with women activist groups to make a difference in the lives of girls & women.

To embody the "whole woman" ” concept, I have learnt to value my safe space where I'm learning to be comfortable in my skin, be vulnerable, practice self care, build relationships and be honest. Yes, I have my dark moments but I'm happy for my support system. I am owning every word used to describe me; Tomboy? Hell yeah! Feminist? Of course! Boss? Yes I am! Thick? Yes! Whole Woman? Yes!

Dear woman, being a whole woman does not mean you are void of flaws, or have it all figured out. Who does? We are all just figuring life out in our own unique way.

Let me end with my favorite quote about being a whole woman by Maame Afon Yelbert-Obeng, “As a whole woman you bring all of who you are into everything you do”.

Davephine Tholley is a young vibrant Sierra Leonean, Civil Engineer with the relentless drive to effect change, willingness to lead and commitment to serve.

Poda Poda Philosophy

My dad tells me that way before I was born, his first job was as a driver. He left home when he was 14 years old to explore a world beyond what his village could offer him. The man did not like to farm at all. So he forged some documents, added two years to his DOB and got a commercial driver’s license to pay the bills. No food for lazy man.

It is hard work being a bus driver en Afrique. You wake well before everyone else and you are usually the last to go to bed. Otherwise, how would the masses move around? In between, you deal with irate passengers, corrupt traffic police, overworked shock absorbers, dishonest mechanics and a very snarky assistant who probably skims the fare. If you’re one of the lucky ones, you actually own your bus, if not you have one paranoid owner perpetually questioning your integrity. Monkey work baboon chop.

Read more at https://labellevieephemere.com/2015/04/21/poda-poda-philosophy/

This Golden Badge of Honor

January 6th, I can still remember the hate in their fingers when they wore this badge of honor on me- it was a brutal merit, a verdict of unconscious merriment and injustice. Burned bridges, soul injured- they left me to unpack with eye lid and bruised kneecap, couldn’t turn back because they burned down my bridge. Do I really deserve this golden badge of honor?

January 6th, Boom Boom 💥everywhere like my heart beat their guns bleat but with a different language of I hate you, they break me. Crave to put forth my future at stake- I could have been a basketball player, an instrumentalist, a footballer, an engineer and many more.They literally killed my dreams.

Tick tick⏱ every night time whispered in my ears, telling me not to worry because he is the best doctor “I heal and Gods time is the best,” .Thus, I beg to ask the question- do I really deserve this golden badge of honor?

January 6th, I was only 3 years old when they came . Nothing to bargain for but a will so free.They refused to see the innocence in me, they let my blood be the signature to a treaty between chaos and solidarity. A solidarity to peace ,they say, a peace I cannot find . Do I really deserve this golden badge of honor?

January 6th, an event that left a mark on the forehead of our nation, exposed this beautiful country and it’s people to the invasion of corrupt minds. Corrupt men with gifts of a wordsmith, architects to our blood spills and when it comes to giving, they are stingy as iron-smiths. I have blatantly refused to to accept anything they say to weigh me down. It must be fate- I convince myself. I have this to say -when our fate meets destiny ,we sometimes feel the entire world must be wrong and it wasn’t our time but we must not let these stereotypes leads our minds into oceans of frustration, but rather we must have the courage to mix anger with sympathy, hate with compassion, and above all we must love .

Do I really deserve this golden badge of honor?

Abass Sesay is a Final Year Student at the Department of Sociology & Social Work at the Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone, and a Disability Advocate.