We have another passenger on the Poda-Poda ! Poda-Poda stories chatted with Nadia Maddy, an author, a public speaker and the founder of Indie Book Show Africa. The author shared her writing journey, and tips on how Sierra Leonean writers can pave their own way in the complex world of publishing. Enjoy the ride.

Thank you Nadia for hopping on the Poda-Poda! Please tell us about yourself: Your background, your work as a lecturer and a writer, etc.

I currently live in London and teach Health and Social Care and Professional Development on the Bath Spa University programme. I am an ex pupil from International School and St Joseph’s Convent.

I started my creative experience with the BBC on the 90s TV Series, Video Nation with a video recorder and some ideas, then I decided with a friend to create and produce the Channel 4 documentary, Aliens Amongst Us, which won final selection at the Black Hollywood Film Festival in 2003. I wrote a couple of plays that were performed at The Half Moon Theatre, London.

My first novel, The Palm Oil Stain– a story about one woman’s survival during the civil war took me 3 years to complete not long after I travelled to Sierra Leone to my father Yulisa Amadu Maddy’s funeral in 2014 and noticed that unless you’re a politician you are not commemorated. If you are , it’s in the form of a statue that no one is made aware of. I decided to start The Indie Book Show Africa Creative Writing Competition with PEN Sierra Leone for 11-18-year-old students in conjunction with PEN Sierra Leone. The competition was set up in honour of my father, director, playwright and author, Yulisa Amadu Maddy. I also run The Indie Book Show Africa - which comprises of African Literature recommendations on Youtube and acts as a resource for Writers interested in the African perspective.

When did you discover your love for writing and how did you decide to pursue it? Was it an easy journey?

I didn’t really discover a love for writing. Some people discover a love for it later on but that wasn’t me. It was always in me. Always. I was always writing poetry and stories as a child. I didn’t grow up with my father until I was 15 yrs old. Before that he would visit and I would spend random weekends with him. As a child I remember him being an African political activist more than an artist so I didn’t get to witness any form of art around him. So my writing as a child was from a place from within. When I did live with him for 2 years in Leeds, W Yorkshire, I was part of his drama production and toured the UK with Gbakanda Tiata. At the time, I wanted to be an actress but this was not an option for me as I was expected to go to university, so I turned to TV production and then writing. I wrote a lot of poetry during that time but the novel writing came much later. I decided to write ‘The Palm Oil Stain’ after going to Sierra Leone in 2006 and 2009. I saw how women were affected and yet everyone was talking about child soldiers. So I decided to write about what I saw after discussions with women who remained invisible during my visits.

Tell us a bit about your writing process? How did you work on the Palm Oil Stain (writing to editing) .

I just wrote it. I thought about it for 18 months. I had the story in my head from beginning to end. I developed everything in my head. Then I started writing it. I didn’t have any plan or plot written down. I wrote everything down by hand and then transferred it to my lap top. Then I saw the mistakes and gaps that needed to be corrected. After that I sent it out to beta readers (friends who were willing to read the first draft) who were people I knew would tell me the truth. That was the best part – receiving their feedback. I’m not afraid of criticism. I think the more criticism you get the quicker you can move forward with your work. Criticism is the best. Criticism makes you fly.

I did three rewrites before it was published and rushed it to an editor. I needed to get my book out before the Charles Taylor trial ended in The Hague, Netherlands. The book was published just before the verdict and I haven’t looked back.

How can Sierra Leoneans support you in carrying on your father's rich legacy in the arts? Especially young Sierra Leonean writers and creatives.

I work with PEN Sierra Leone to have the Creative Writing competition promoted in schools around the country. The first prize is £100, second £50 and third, £30. So far we have had more than 6 winners and I welcome all young people between the ages of 11-19 yrs old to take part. They can contact PEN Sierra Leone, Campbell Street. Contact Allieu Kamara or Nathaniel Pierce or directly indiebookshowafrica@gmail.com

What advice can you give to young Sierra Leonean writers who want to publish their work internationally?

I have met a lot of young Africans who are writing and publishing without waiting for approval from the big boys. Those days are over. There are a lot of publishing houses all over Africa as well as UK, Europe, America and Canada. Africans should be thinking about publishing in places like India, China …possibly even South America.

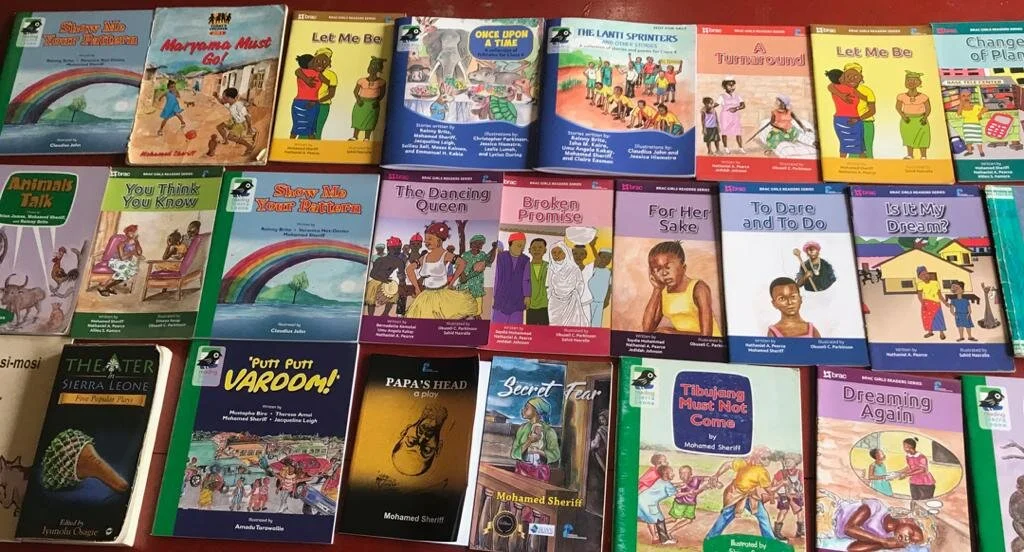

Publishing in Africa is a thing too. Now, you can upload your book to the Nigerian publishing house - Okadabooks.com and start selling your book straight away - make some money. Things have changed dramatically. We have a publishing company in Sierra Leone run by Mallam O, The SLWS Series - https://sl-writers-series.org/index.php/en/ They also help and support young writers. I understand that it is a lot to take in and there is in fact so much opportunity it can be overwhelming. But I think we need to realise that we can publish around Africa as well as internationally. The mind-set has to change, once your book is written it has become a product that you are going to sell, so you have to think about the different distribution points that you want to sell your book to.

One of the main concerns that I have is editing. Young people are not aware that they need to get their work edited and that can be expensive. It’s an African problem and one that writers and publishers are trying to tackle. If you can get your teacher or a member of your family to edit your work it’s a good start but if you want to publish internationally – then your work has to be seen by a manuscript developer, a copy editor and a proof reader before you can think about having a chance at being accepted. We all know that we don’t have those resources. So this is a problem.

That’s why SLWS series and PEN Sierra Leone may be good places to get the resources and experience that can help you attain the next level.