"A professional opportunity"- Poda -Poda Stories Fellow Sulaiman Bonnie's reflection

The Poda-Poda Stories Fellowship is a year-long program that is designed to support young Sierra Leonean writers to grow in the literary industry and manage an independent creative project.

The goal of the fellowship is to inspire and train the next generation of young writers in Sierra Leone. Through access to resources, coaching, training, and support for their independent projects, we hope that fellows will enhance their creative skills, while gaining exposure to the literary world of publishing, writing and editing.

Poda -Poda Stories Inaugural Fellow Sulaiman Bonnie reflects on his work over the past year and talks about his independent project— an anthology of poems from students.

Oumar Farouk Sesay on the Transformative Power of Poetry

Oumar Farouk Sesay is a published poet, novelist, and playwright. He was resident playwright of Bai Bureh Theatre in the '80s, and he has written several plays. He has been published in many anthologies of Sierra Leonean poets, including Lice in the Lion's Mane, Songs That Pour the Heart and Kalashnikov In The Sun. He is the President of PEN, Sierra Leone chapter. Using vivid imagery and metaphors, Sesay’s poems are beautifully woven, richly capturing the heartbeat of Sierra Leone. It was an honor to interview him, and he shared his creative journey with Poda-Poda Stories.

Poda-Poda: Thank you for granting me this interview. Tell us a little bit about yourself, your background, and your career as a poet.

FS: Thank you very much and I am delighted to a part of this. I started writing as early as in my teen years when I was in sixth form. Those were the days of theater groups in Sierra Leone. I was commissioned to write a play for Bai Bureh Theater Group, which was performed at City Hall, and that was my maiden work as a writer. Then I started dabbling with poetry here and there, but not in a serious way as I had engaged with theater. It was later in life that I started writing poetry. Then after university, I worked as a journalist briefly, for local newspapers like The Chronicle newspaper, and International papers like West Africa magazine. Later, the calling for poetry was so strong, so I became a poet. Occasionally I do articles for newspapers, but I am much more engaged in poetry writing than other forms of writing.

I came to the U.S. and I was fortunate to publish my first collection of poems “Salute To The Remains of a Peasant”. Those are poems that captured, events during the war in Sierra Leone. I later published another collection of poems, written post-war poems and some other themes of corruption and antisocial activities within the country. That collection was “The Edge Of A Cry.” Then after that, I was able to publish my first novel, “Landscape of Memory”, which addresses the theme of the war and its impact in Sierra Leone. I was also a Cadbury visiting Fellow, at the Birmingham University in the U.K and a fellow at the Baptist University in Hong Kong.

Poda-Poda: You mentioned you were into journalism and then you took up poetry later. How did that transition happen?

FS: It is difficult to place a finger on it, because poetry has a magnet that pulls a writer than other forms of writing. I felt preoccupied with issues happening around me, mostly during the war, and I started capturing it in metaphors that were so strong that I thought if I put them in prose, I might not have been able to capture them as exactly as they were.

Poda-Poda: Tell us about your new book, 400 Years of Servitude. Why did you decide to write this anthology?

FS: 400 Years of Servitude is mostly a collection of poems that deal with the theme of race relations and the impact it has on African Americans and Africans. There are cultural forces in international politics that tend to dictate the way we (black people) are treated all over the world. For example, policy makers in America and in the Western world, have a tendency of treating Africans in a manner akin to the way African Americans here are treated, like a lower caste of people. I was basically trying to see a correlation between the treatment of Africans and African Americans here in America. I saw that the connection is race. I started putting together poems that largely deal with race and race relations, and I did a span of 400 years, from the time the first slave was transported from Africa to the New World to date. There are poems that deal with the Middle Passage, and that deal with African Americans. That is why I called it 400 years of servitude.

Poda-Poda: That is a very good title. I interviewed Ishmael Beah and asked him a similar question to this: As a black writer living in the U.S, do you think it's your duty to write about global blackness or the global perception of blackness?

FS: Well, I think so. I wrote a poem about race relations called “The Look”. When you go into places here in the US , you are given a look that carries with it the burden of servitude, the look carries the historical baggage that was given to our brothers when they were chained in the plantations of yesteryears.

This look follows like a chain on your soul wherever you go. It became apparent that my African-American brothers were also giving me a look of a similar slant as if I am the Judas who sold a brother for thirty pieces of silver.

An excerpt from the poem is “brother, don't look at me. The look that they look at me for looking like you.”

Yes. the question of race relations must be addressed by authors for the benefit of the entire race. Writers do not write in a vacuum, you must really make sure your work has affinity to the reality around you, and race relations concerns writers everywhere in the world. I think as Sierra Leonean writers, we should be concerned with that too.

Poda-Poda: Your work has a lot of imagery and touches on a lot of themes. Some recurring themes in your work are patriotism and healing. How do you think literature, especially poetry, can help heal our nation and move us forward?

FS: Interestingly, we had a group that was formed during the war that was called Falui Poetry Society. Most of the prominent Sierra Leonean poets were members of that group, and we were able to organize poetry reading in public places and in private places. The reason being, poetry itself has a healing power.

As a collective, we published our poems at a time when the Special Court began in Freetown. Fortunately, the prosecutor, David Crane, was present when we launched the book that we published. “Songs That Pour The Earth” was the first collection we ever put together as an anthology that captured the poems of the war. He was at the launch and he bought the book. During the opening remarks of the Special Court, he read a poem by Sydnella Shooter, which chronicled the atrocities during the rebel war.

So as poets, we are witnesses. Just as Walt Whitman and other poets were witnesses to the American civil war, Sierra Leonean poets bore witness of the war in Sierra Leone. And we captured it in ways that will forever be there for posterity to see. We happened to be the first prosecution witness called upon to account for what we saw and felt during the eleven-year war.

Poda-Poda: You were a resident Playwright for the Bai Bureh Theatre, and you have also published several books. Of course, it is not a secret that it is a challenge being a creative person in Sierra Leone. What are some of the challenges that you faced and how have you been able to hold on to your craft for so long?

FS: From a personal point of view, writing is a very private project, a very private exercise. It starts as a migration from your mind to the public and that route is hurdle- prone in ways that affect the tenor and texture of the work created.

In the creative process you sometimes think in your native tongue and haul the thought to the page in another – this process done mostly at a subconscious level. You do not even know you are doing that. You may not even know that you are doing that until an idea from one culture refuses to yield meaning in another language. In the process of doing that, the question of how you maintain the balance to make sure that the purity of your thoughts is not is not diminished in another language? Those are creative challenges and poetic license sometimes help us navigate through those hurdles.

The bigger challenge though, is how seriously people in Sierra Leone and mostly other African countries take their writers. Writers have been on the forefront of the struggle for the independence of the continent. If you check South African history for example, writers like Dennis Brutus played an important role in making sure the of apartheid was exposed. In Nigeria, Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe contributed immensely in enhancing the creative image of the country and in promoting democracy. Thanks to them the expectation of the public from writers goes beyond the literary. The image of writers as agents of change put them in direct confrontation with authority sometimes with disastrous effect to the writers.

We come into writing with the onus of not only doing art for art's sake but with a manifesto to usher change. Ours is not art for art sake but art you can use to usher change; those who wants the status quo to remain unchanged perceive writers as opponents.

And of course, the question of readership is another big problem that we have. Most people started reading me when one of my poems made it in the West African exams’ syllabus- hence reading me becomes a matter passing or failing exams.

So, we must create a climate whereby we grow big at home, then seek recognition outside. In our own case, it’s the other way around. I think it’s because we have the “made in UK mentality” wherein we grew up buying sneakers that are made in the UK, so we also think that our talent must be made somewhere else before it is respected at home.

Poda-Poda: That is also an issue that's very interesting because I do agree with you that we tend to value creative work that’s acknowledged in the US or the UK, while people are making good work here at home too. That’s why I want Poda-Poda Stories to highlight the work being done at home too.

FS: The work Poda-Poda is doing is so good. There was a famous Sierra Leonean playwright, Kolossa John Kargbo. He was one of the best back in the day. He died in Nigeria and he was buried there. And just this year his play “Let Me Die Alone” is also been included in the West African exam syllabus. He also wrote Tabita Broke Ose, a comedy, and I’ve seen fragments of his work being projected in some social media posts lately, and I wonder about the fate of his many manuscripts.

We must have pride in who we are as a people. It's very important that some of us keep writing. It is difficult for a nation to exceed the potential of the story they narrate to themselves. The stories we tell each other, the stories we narrate of ourselves determines who we are as a nation. A story that constantly says “Salone nor betteh” might just create a failed state.

Poda-Poda: In what ways do you think literature, and the creative arts, has the function to shape our society as Sierra Leoneans, especially for the younger generation ?

FS: When we start to use language in the abstract, we start to use language to imagine a reality that is not yet in existence. Language give us the ability to create fiction. It is the creation of the fiction that sets human beings apart from other species.

In A Brief History of Humankind, Yuval Harari says because we can use language, we are able to create that which does not exist. And we create institutions that are creation of our imagination. We talk about human rights for example. You know, these are not concrete things, but because we are able to use the language to create that, we are able to organize society around the concepts that are not concrete. That is the power of language. We can imagine things that are not in existence and we can use that imagination as a signpost to guide us into greater good. Literature inspires, and it helps young people to imagine. For most people, the truth of fiction is the only truth they cling to in their journey through life.

Find out more about Oumar Farouk Sesay’s work at farouksesay.com

Questions and interview by Ngozi Cole.

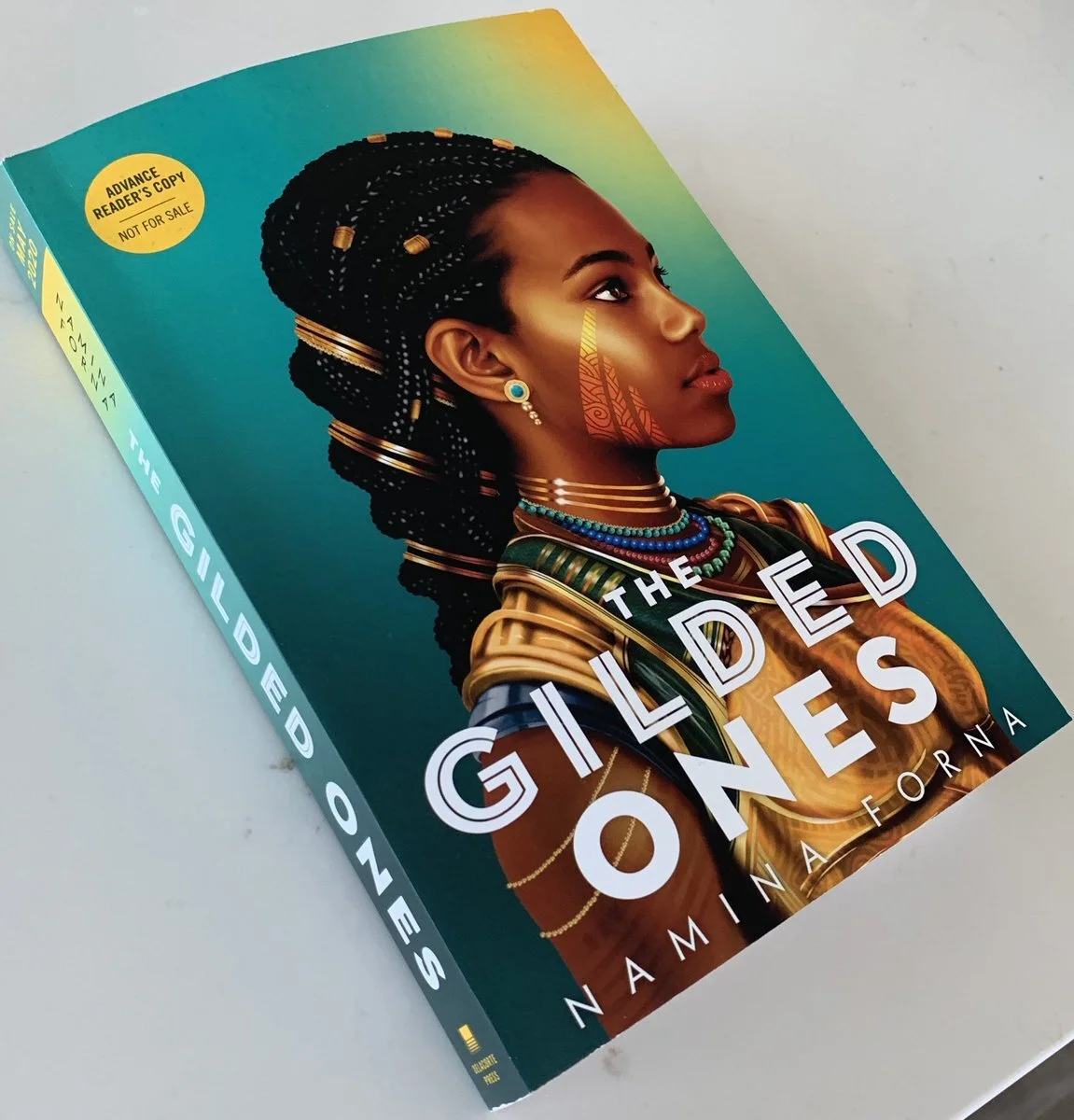

Namina Forna on Writing and Creating New Worlds

Women bleeding gold, outcast warriors shifting power, and a fierce sixteen-year-old heroine: this is the world that screenwriter and novelist Namina Forna has created in her Young Adult (YA) fantasy trilogy The Gilded Ones. Namina Forna was born in Sierra Leone and moved to the US when she was a child. Her memories of stories in Sierra Leone have richly influenced how she creates epic fantasy worlds, and we are proud to call her one of our own! Poda-Poda Stories reached out to Namina, and she shared some amazing gems with us. Dive into her journey as a writer, the need for representation, and how writers can navigate the publishing industry.

Poda Poda: Please tell us a bit about yourself: your work as a screenwriter and a novelist etc. Was writing something you always wanted to do and were you encouraged to pursue it?

Namina: I’m a fantasy author and screenwriter in Los Angeles, working on books and movies and TV shows. Honestly, I was always meant to be a writer. Even though I only officially decided on it when I was in my late teens, I showed all the signs. I was one of those kids who always had their nose in a book, and I basically lived at the library growing up. I also watched way more TV than was advisable, so there’s also that.

My family, of course, wasn’t very happy with it. They had all these grand ideas that I was going to be a lawyer, maybe do international diplomacy, but it wasn’t for me. I’m quiet and shy by nature, so I don’t have the temperament for it. I hope I’ve made up for their disappointment somewhat.

Poda Poda: You are from Sierra Leone, and moved to the US when you were a child. What was that transition like for you and how has it informed your journey as a writer?

Namina: It was a very rough transition. I moved to Lawrenceville, Ga, in the fall, and of course, I hated it. I wondered why the grass was always so yellow, and why it was always so cold. Fitting in at school was difficult. People have this image of what “Africa” is like, so when I told the kids at school that I grew up in a nice house and not a hut, and that I had lots of clothes instead of walking around naked (like they repeatedly asked me), my teachers told my mom that I was a habitual liar, and that I needed to be checked for mental issues.

It’s definitely informed my journey as writer. My biggest writing goal as of the moment is to change the opinion people have of Africa—not just foreigners, but natives ourselves. I think that one of the most horrendous things colonization did was rob us of our imagination, and by extension, pride in ourselves. Even though we have a glorious history and a beautiful culture, we can’t see it because it’s been overwritten by colonial powers. So we have to overwrite them back, one story at a time.

I write so that Sierra Leoneans, so that Africans and other black and brown people can see themselves as heroes and fight against the mental oppression that is the result of all our years of colonization, etc. That way, the next time some white teacher calls an African kid a liar to their face for saying they didn’t walk around naked and have lions in their back yard, they can point to my book or movie and tell that teacher to go shove it where the sun don’t shine.

Poda Poda: We are so excited about your book The Gilded Ones. The main character Deka, resurrects every time she's killed (if I'm correct?), and that is very symbolic. What aspects of your background as a Sierra Leonean woman, either influenced or informed writing it? Additional fun question, would you describe it as a Feminist book?

Namina: Yes, Deka resurrects when you kill her, and she bleeds gold as well, which is also symbolic. The gold is meant to talk about how women’s bodies are seen as objects, either for sexuality or labor. So often, we’re reduced to the terms of our usefulness in these aspects. This definitely came from my anger growing up as a girl in Sierra Leone.

I think when you grow up as a woman in Sierra Leone, or in any other patriarchal society (which is basically everywhere), you grow up angry and confused. Because your body and your person are not respected or valued, especially in comparison to men. And if it’s not the little things like the automatic expectation that you cook and clean and serve everyone, it’s the assault, the rapes, the trauma that follows.

I grew up during the civil war, and I’m so lucky that I never really experienced much of it. But so many of my cousins were taken, disappeared to the bush to become sex slaves, etc. You hear the stories, you see the trauma. All I can do is bear witness.

So, am I a feminist? Yes, definitely. I know a lot of people see the word and their eyes immediately glaze over. To them, feminism means women coming for men’s rights, which is obviously not the truth. “When you’re used to privilege, equality feels like oppression,” as the saying goes. For me, feminism means having an equal chance. Am I ever going to be an NBA player? No, but neither is the vast majority of the male population. We’d still all like an equal chance to shoot that shot, though.

Poda Poda; I love Fantasy! I am a huge fan, and what I like about what you've done is representation, the ability for a Sierra Leonean to pick it up the book and go " hey, I know the word alaki, etc ". Were those things intentional? Did you want it to also be a story about representation?

Namina: Yes, very much so. My work is always inspired Sierra Leone and the youth of the nation, because they’re where the future lies. Whenever I write, I always extend this invitation to them: this work is for you. Know that I’m here, creating things for you, and even though it’s going onto the world stage, it came from Sierra Leone first. As for the word, alaki, it’s an in-joke for our country. We all know alaki means useless. So I took the word, and I took it one step further. I hope that if The Gilded Ones becomes an international thing, Sierra Leoneans will stop and laugh, because now we have the entire world saying alaki. The thought always brings me joy.

Poda Poda: There are young Sierra Leoneans writing at home and in the diaspora , and many of them want to get published internationally . We interviewed the author Nadia Maddy recently and she shared that Sierra Leonean writers have to go past the gatekeepers of publishing and find ways to get their work out there. What advice would you give to writers, especially writers in Sierra Leone, about the publishing industry, managing rejection, and just forging ahead, given that Sierra Leone is a difficult landscape for creatives ?

Namina: The first thing I will say is work on the craft: learn from the masters, read everything you can get your hands on, find incisive critique partners that will help you take your work to the next level. Also, make sure you have the correct word count. Don’t write 100,000 words if you’re working on a middle grade comedy, for example.

Once you have that down, get on Twitter. Twitter is where authors and agents hang out, and you can join a global community once you’re plugged in.

To get your work to the gatekeepers, there’s three main avenues: literary magazines, querying, and twitter competitions. Agents read literary magazines, and if you publish your short stories there, you could get that special email. There’s also querying, which is when you write a cold email to an agent, asking them to represent you.

Some advice on querying: Make sure that the agent you’re emailing likes the kind of work you do. For example, if you’re writing gothic horror, don’t send it to someone who likes middle grade fantasy, they’ll never talk to you again. You can use resources like the official manuscript wishlist, https://www.manuscriptwishlist.com, where you basically just plug in what genre you’re writing, and can see all the agents that accept what you write. You can also go to websites like Query Shark and pitch wars to find out more.

Speaking of Pitch Wars, twitter pitch competitions are amazing for helping black writers get their work to agents. I got my big break through #DVPit. That and Pitch Wars and #PitMad get a ton of black authors agented, so check them out. Also, you make a lot of friends doing those competitions, and those friends eventually become authors.

Poda Poda: What's your writing process like?

Namina: Typically, I get my ideas from dreams. Once I wake up, I immediately write the idea down, then I talk it over with friends, agents, etc., to make sure it’s original and marketable. Not every idea is, and you have to know which ones to toss away and which ones to keep. When I came up with The Gilded Ones, for instance, it wasn’t marketable, but I knew it was an original idea, so I kept it, and waited until the time was right.

Once I’ve ensured an idea is good, I begin my research, which takes about a year. I do this passively, while I’m working on other projects. At the end of the research process, I finesse my story and write down an outline. From there, I go to pages. I try to write ten pages every morning before breakfast. If everything is good, and my schedule is okay, I usually finish a book or a new work every three, four months or so.

Poda Poda: Finally, any last word for Poda-Poda Stories and your Sierra Leonean fanbase ( we boku! )

Namina: Fambul-dem, I’d just love to see you guys when I come back to Sierra Leone. If COVID gets better, I’ll definitely be at Ma Dengn this year. And if not, I’ll return to Sierra Leone at the earliest opportunity. Until then, stay safe, everyone.

Visit Namina Forna’s website at naminaforna.com.