A Writer's Insight: Pede Hollist Talks To Poda-Poda Stories

Pede Hollist is a Sierra Leonean writer and a professor of English at the University of Tampa, Florida. His short story, “Foreign Aid,” was shortlisted for the 2013 Caine Prize, arguably Africa’s most prestigious literary award. His first novel, So the Path Does Not Die (Jacarandabooksartsmusic, U.K.), won the 2014 African Literature Association’s Book of the Year Award: Creative Writing, and his short stories have been published in several platforms. Pede Hollist shared his journey with Poda-Poda Stories in this interview.

Poda- Poda: Please tell us a bit about yourself (background, your work as a writer, academic, etc.)

Pede: My name is Arthur Onipede Hollist, but I write as Pede Hollist. I was born in Freetown, Sierra Leone. I am currently a professor of English at the University of Tampa, where I teach academic and creative writing as well as African Literature.

Poda-Poda: You have rich collection of work (including a short story that was shortlisted for the Caine Prize). Tell us how you started out as a writer.

Pede: I stumbled into writing fiction in my late forties. Apparently, I often told amusing tales to my department colleagues. One of them encouraged me to convert them into written stories. I did, and Path, my first novel, was the result. I would not encourage beginning writers to skip the apprenticeship of short fiction and nonfiction narratives because writing a book is a mammoth task. Still, determination can overcome most challenges. Before writing, I mostly read. By the end of primary school, I had read all of the 20-book children’s classics my parents bought for my siblings and me. After I completed them, I started reading the entries of the adjacent encyclopedias. No, I did not read all of them! Instead, I played cricket, football, and ran track. Diverse interests and activities enrich one’s outlook and provide a deep fund of experiences to tap into when writing. In secondary school in the UK and Sierra Leone, I read the novels of Richard Gordon, P. G. Wodehouse, and James Hadley Chase. Of course, as a college student and now as a professor, I read a broad range of literary texts. Reading enabled me to become a writer.

Poda-Poda: Tell us a bit about your writing process.

Pede: I am always looking for ideas and incidents to turn into stories. I take notes , do research, and free-write if an angle or insight on a subject grabs me. My phone is full of catchy phrases, quotations, and well-written sentences. I read books in print and e-formats, listen to audiobooks, and attend author readings. I daily listen to the news, to people telling stories, and to stand-up comedians. I learn from them the importance of set ups, timing, pacing, and punch lines. These elements help me to create engaging, suspenseful writing. Of course, having an idea does not mean you have a story. I spend hours, sometimes days, months, and even years shaping ideas to make them fit with others for a story. For example, an idea for a recent short story titled “Where One Thing Stands” came to me in 2009 when I visited northern Ghana. There, I learned about a longstanding land dispute between the Namogligo and Tindongo peoples. It had resulted in periodic, deadly engagements between the two groups. I wanted to write about this conflict, but I did not feel the subject would make an interesting short story. The idea floated in my head until 2016 when I met a person who self-described as gender neutral and was searching for acceptance from family and friends. After some research, I combined this individual’s desire with the dispute between the warring ethnic groups into a story about difference, conflict, and coexistence. Of course, this process works best when you have time. Often though, you have to shoehorn your ideas into a story because you have a deadline to meet. I can do that too. So the takeaway is, be adaptable.

Poda-Poda: Your novel, So The Path Does Not Die, focuses on home and exile and belonging to a place. It also touches on certain "sensitive topics." How important do you think it is to address what would be considered sensitive topics in literature (e.g, FGM, ethnic discrimination, war trauma, etc.) through literature?

Pede: Very important, but I don’t think that should be the goal of writing literature. People don’t read novels and poems because they want to learn about sensitive topics. They read because they want to be immersed in an aesthetic experience. Hopefully, careful handling by authors of the subjects mentioned in your question exposes readers to insights without putting them under pressure to take positions and make judgments. My goal in telling stories, sometimes with a smile and at other times a snarl, is to show that issues are more complex than we imagine.

With that goal, I stay alert to places where I may be engaging in agenda-writing. To ensure I accurately and ethically represent groups of people and thoughtfully deal with sensitive subjects, I do my research. For example, before and during the writing of Path, I read Michael Jackson’s Allegories of the Wilderness, other ethnographic studies of the Kuranko, and interviewed several of its members. To get a comprehensive understanding of circumcision, I read many articles, especially those of Fuambai Sia Ahmadu, a robust defender of the practice, interviewed, and surveyed many people. Over time, I was able to inhabit the different perspectives before reproducing them through character and dialogue. Yet at a literary event in Kenya, one audience member told me that my story did not advocate for stopping FGC and noted that was an attitude those of us who lived in the west could afford to adopt. So, regardless of your efforts, readers engage your work with biases and agendas, and insensitivities arise where you might have intended none.

Poda-Poda: Your short story Foreign Aid was shortlisted for the Caine Prize. Please share the process of how it happened.

Pede: Like many other Africans, I have listened to the arguments about the pitfalls of foreign aid. Many Africans returning to their birth lands from the diaspora have functioned as donors and bearers “of aid.” I am one among many. In the native land, we consciously or unconsciously play up our “overseas-ness” and benevolence, sometimes to show off, but often in response to an overwhelming presence of material poverty and need. However, we quickly realize that our assistance is inadequate or misused. Take the laptop gifted to a nephew, niece, or friend, sometimes with much fanfare. Not long after, we learn the device is no longer working. It fell and the screen broke, got soaked by torrential rain, was fried by power surges, or ravaged by viruses (including older strains of the Coronavirus). These things happened to it serially. For each, you send replacement parts and money for repairs. Then it got stolen! Talks about a new waterproof, fire-resistant model with the latest antivirus and updates are underway. But donor fatigue is setting in. Oh, did I say I wrote the story because I wanted to laugh at myself, other donors and recipients who have been through this aid experience ? If readers recognize the parallels between personal and international assistance, and that tangled motives, interests, and personalities underline and undermine giving, that’s a good outcome.

Poda-Poda: How can more Sierra Leonean writers bring or highlight their work on international platforms?

Pede: They must present well-edited works to the curators of international platforms. Because all writers suffer from word blindness, hand over your manuscript to skilled editors or experienced writers. They will point out inconsistencies with the subject matter, plot, and characterization. They will identify opportunities to improve craft elements, grammar errors, typos, and format issues, especially those pesky ones that pop up in editing.

Join Facebook communities of writers, editors, and publishers and develop relationships. Subscribe to platforms that publish contemporary African writing. Submit your work to them. My favorite is Afreada. It presents a range of exciting, relatable, and easy-to-read stories. It even tells you how long it would take to read each story, typically from three to eight minutes. Read those stories and the responses to them to get a sense of the themes, issues, and styles that are current and appealing. Imitate them for sure, but to catch attention, you have to break away from popular trends and do something different.

Regularly visit the websites of your favorite authors and follow them on Twitter and Instagram. To keep current with what’s happening in the field, subscribe to James Murua's Literature Blog. It has a country section and a comprehensive list of competitions and publishers. Submit your work to as many sites as possible, making sure you respect those that do not accept simultaneous submissions. I recently learned of Rigorous, “a journal written and edited by people of color.” However, be prepared that you are not going to be placed or listed more times than you are. Stiffen yourself for the rejections. Brush them off and keep writing, revising, and submitting.

Poda-Poda: How can Sierra Leonean creatives (both at home and in the diaspora) collaborate to bring our rich literature to international platforms, or should we focus on building a strong literary scene in Sierra Leone first?

Pede: Yes, focus on strengthening the workshops, competitions, artists’ organizations, and festivals already in place and collaborating to extend them throughout the country. Showcasing the country’s rich literature is the product of good writing. Nigerians, Kenyans, and South Africans dominate the African literary scene because they have more established creative writing cultures-frequent workshops and author readings, more secondary school and college elective courses, competitions, publishers, and websites.

During my 2017-2018 Fulbright year in Sierra Leone, I conducted workshops at Modern High School, Harford Girls School (the one on Circular Road, Freetown), and at a community program named Bright Light Youth Empowerment. The students in these sessions were enthusiastic and had stories to tell. Their curiosity, interests, and talents have to be sustained and developed. We need more competitions such as those offered by Aminatta Forna and Nadia Maddy, book festivals, and reading clubs.

To that end, I am going to be starting my literary blog. It will be another space for Sierra Leoneans to display their work. If we build such sites with quality material, the international audience will come to read our rich literature. Then we should host in-country writers’ retreats. I would love to be part of a two-week residency somewhere in the hills of Kambia. That’s a project to collaborate on.

Poda-Poda: What advice would you give to young creative writers living in Sierra Leone?

Pede: Study Sierra Leone’s cultures, arts, and histories. Pay close attention to the trends today, especially among your peers. Write about them, not to teach, preach, and engage in social criticism, but to immerse your readers in the worlds or subcultures you create. Write in Mende, Temne, Krio and other local languages, or lightly incorporate indigenous vocabulary, expressions such as fiam and kitikata and intensifiers like o and ya into your English-language pieces. Incorporate oral storytelling stylistics like repetition, parallelism, piling and association into your writing. Play and experiment.

Read beyond the contemporary African, British, and American texts that are taught in schools and colleges. Africa’s Sunjata and Mwindo epics, India’s The Ramayana and The Mahabharata, Japan’s The Tale of the Genji and The Tale of the Heike, and China’s The Book of Songs are a few examples of the breadth of world literature that could help your writing.

Become a voracious consumer of non-literary material. Knowing about economics, accounting, anatomy, cosplay, gender issues, psychology, and a thousand and one other topics can be surprisingly helpful when you are writing. Look on Youtube and Google videos that teach about writing.

Don’t make excuses about not having the time to write.Write, every day, until you have a completed draft. Then revise until you believe it is the next great work the world has been waiting for. Finally, send it to skilled readers who will tell you the work can’t possibly go out into the world as currently dressed-- you know, like your parents said to you when you wore that gaudy shirt or revealing dress. The experienced readers will have suggestions and comments that will make your great work better. Still, don’t change your narrative because someone thinks you should. Weigh suggestions, use and adopt what feels right, and set aside what doesn’t. You will get rejection letters (many of them) and fail to place in competitions. Don’t give up. Keep writing. Success is around the corner.

Namina Forna on Writing and Creating New Worlds

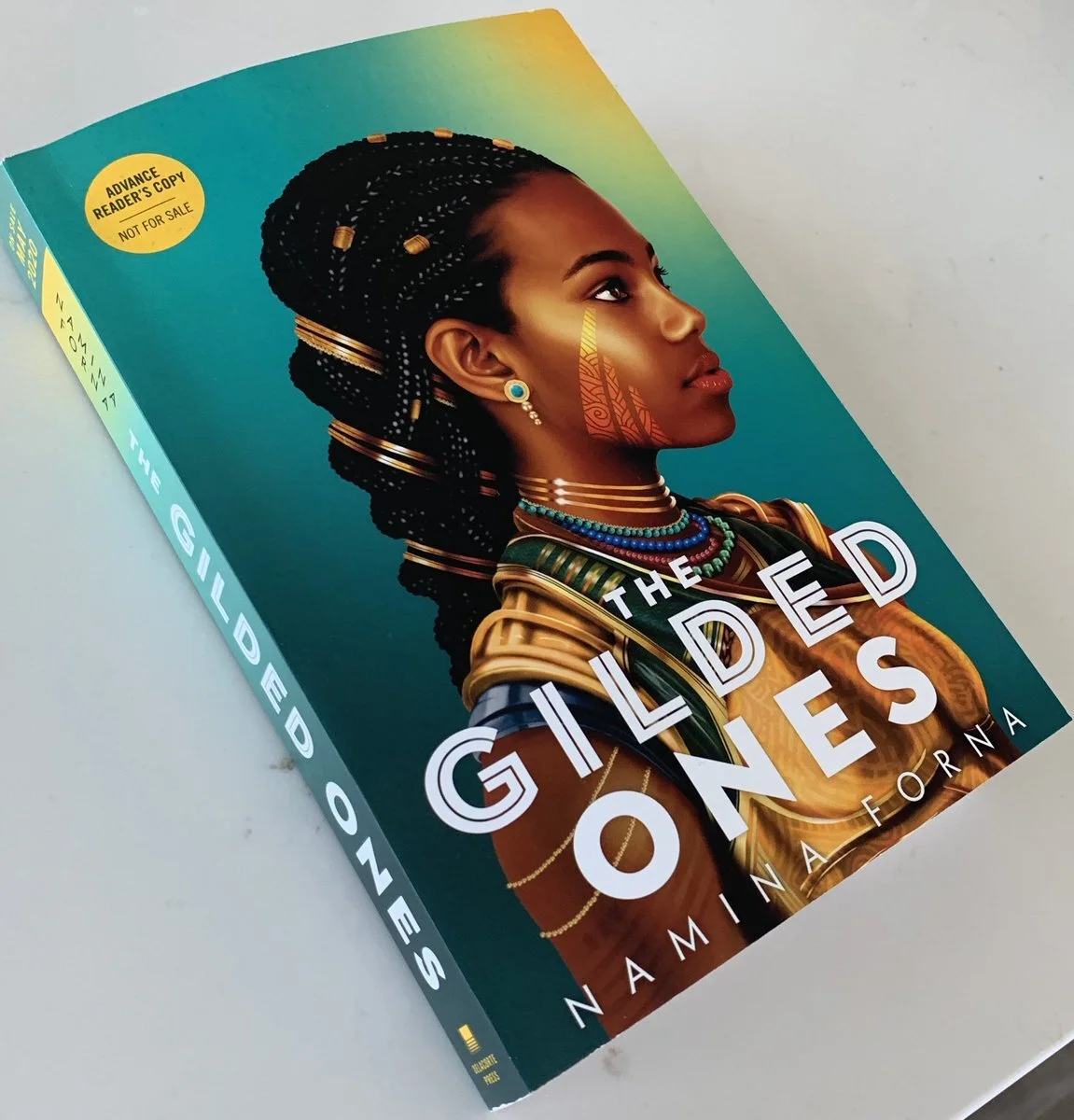

Women bleeding gold, outcast warriors shifting power, and a fierce sixteen-year-old heroine: this is the world that screenwriter and novelist Namina Forna has created in her Young Adult (YA) fantasy trilogy The Gilded Ones. Namina Forna was born in Sierra Leone and moved to the US when she was a child. Her memories of stories in Sierra Leone have richly influenced how she creates epic fantasy worlds, and we are proud to call her one of our own! Poda-Poda Stories reached out to Namina, and she shared some amazing gems with us. Dive into her journey as a writer, the need for representation, and how writers can navigate the publishing industry.

Poda Poda: Please tell us a bit about yourself: your work as a screenwriter and a novelist etc. Was writing something you always wanted to do and were you encouraged to pursue it?

Namina: I’m a fantasy author and screenwriter in Los Angeles, working on books and movies and TV shows. Honestly, I was always meant to be a writer. Even though I only officially decided on it when I was in my late teens, I showed all the signs. I was one of those kids who always had their nose in a book, and I basically lived at the library growing up. I also watched way more TV than was advisable, so there’s also that.

My family, of course, wasn’t very happy with it. They had all these grand ideas that I was going to be a lawyer, maybe do international diplomacy, but it wasn’t for me. I’m quiet and shy by nature, so I don’t have the temperament for it. I hope I’ve made up for their disappointment somewhat.

Poda Poda: You are from Sierra Leone, and moved to the US when you were a child. What was that transition like for you and how has it informed your journey as a writer?

Namina: It was a very rough transition. I moved to Lawrenceville, Ga, in the fall, and of course, I hated it. I wondered why the grass was always so yellow, and why it was always so cold. Fitting in at school was difficult. People have this image of what “Africa” is like, so when I told the kids at school that I grew up in a nice house and not a hut, and that I had lots of clothes instead of walking around naked (like they repeatedly asked me), my teachers told my mom that I was a habitual liar, and that I needed to be checked for mental issues.

It’s definitely informed my journey as writer. My biggest writing goal as of the moment is to change the opinion people have of Africa—not just foreigners, but natives ourselves. I think that one of the most horrendous things colonization did was rob us of our imagination, and by extension, pride in ourselves. Even though we have a glorious history and a beautiful culture, we can’t see it because it’s been overwritten by colonial powers. So we have to overwrite them back, one story at a time.

I write so that Sierra Leoneans, so that Africans and other black and brown people can see themselves as heroes and fight against the mental oppression that is the result of all our years of colonization, etc. That way, the next time some white teacher calls an African kid a liar to their face for saying they didn’t walk around naked and have lions in their back yard, they can point to my book or movie and tell that teacher to go shove it where the sun don’t shine.

Poda Poda: We are so excited about your book The Gilded Ones. The main character Deka, resurrects every time she's killed (if I'm correct?), and that is very symbolic. What aspects of your background as a Sierra Leonean woman, either influenced or informed writing it? Additional fun question, would you describe it as a Feminist book?

Namina: Yes, Deka resurrects when you kill her, and she bleeds gold as well, which is also symbolic. The gold is meant to talk about how women’s bodies are seen as objects, either for sexuality or labor. So often, we’re reduced to the terms of our usefulness in these aspects. This definitely came from my anger growing up as a girl in Sierra Leone.

I think when you grow up as a woman in Sierra Leone, or in any other patriarchal society (which is basically everywhere), you grow up angry and confused. Because your body and your person are not respected or valued, especially in comparison to men. And if it’s not the little things like the automatic expectation that you cook and clean and serve everyone, it’s the assault, the rapes, the trauma that follows.

I grew up during the civil war, and I’m so lucky that I never really experienced much of it. But so many of my cousins were taken, disappeared to the bush to become sex slaves, etc. You hear the stories, you see the trauma. All I can do is bear witness.

So, am I a feminist? Yes, definitely. I know a lot of people see the word and their eyes immediately glaze over. To them, feminism means women coming for men’s rights, which is obviously not the truth. “When you’re used to privilege, equality feels like oppression,” as the saying goes. For me, feminism means having an equal chance. Am I ever going to be an NBA player? No, but neither is the vast majority of the male population. We’d still all like an equal chance to shoot that shot, though.

Poda Poda; I love Fantasy! I am a huge fan, and what I like about what you've done is representation, the ability for a Sierra Leonean to pick it up the book and go " hey, I know the word alaki, etc ". Were those things intentional? Did you want it to also be a story about representation?

Namina: Yes, very much so. My work is always inspired Sierra Leone and the youth of the nation, because they’re where the future lies. Whenever I write, I always extend this invitation to them: this work is for you. Know that I’m here, creating things for you, and even though it’s going onto the world stage, it came from Sierra Leone first. As for the word, alaki, it’s an in-joke for our country. We all know alaki means useless. So I took the word, and I took it one step further. I hope that if The Gilded Ones becomes an international thing, Sierra Leoneans will stop and laugh, because now we have the entire world saying alaki. The thought always brings me joy.

Poda Poda: There are young Sierra Leoneans writing at home and in the diaspora , and many of them want to get published internationally . We interviewed the author Nadia Maddy recently and she shared that Sierra Leonean writers have to go past the gatekeepers of publishing and find ways to get their work out there. What advice would you give to writers, especially writers in Sierra Leone, about the publishing industry, managing rejection, and just forging ahead, given that Sierra Leone is a difficult landscape for creatives ?

Namina: The first thing I will say is work on the craft: learn from the masters, read everything you can get your hands on, find incisive critique partners that will help you take your work to the next level. Also, make sure you have the correct word count. Don’t write 100,000 words if you’re working on a middle grade comedy, for example.

Once you have that down, get on Twitter. Twitter is where authors and agents hang out, and you can join a global community once you’re plugged in.

To get your work to the gatekeepers, there’s three main avenues: literary magazines, querying, and twitter competitions. Agents read literary magazines, and if you publish your short stories there, you could get that special email. There’s also querying, which is when you write a cold email to an agent, asking them to represent you.

Some advice on querying: Make sure that the agent you’re emailing likes the kind of work you do. For example, if you’re writing gothic horror, don’t send it to someone who likes middle grade fantasy, they’ll never talk to you again. You can use resources like the official manuscript wishlist, https://www.manuscriptwishlist.com, where you basically just plug in what genre you’re writing, and can see all the agents that accept what you write. You can also go to websites like Query Shark and pitch wars to find out more.

Speaking of Pitch Wars, twitter pitch competitions are amazing for helping black writers get their work to agents. I got my big break through #DVPit. That and Pitch Wars and #PitMad get a ton of black authors agented, so check them out. Also, you make a lot of friends doing those competitions, and those friends eventually become authors.

Poda Poda: What's your writing process like?

Namina: Typically, I get my ideas from dreams. Once I wake up, I immediately write the idea down, then I talk it over with friends, agents, etc., to make sure it’s original and marketable. Not every idea is, and you have to know which ones to toss away and which ones to keep. When I came up with The Gilded Ones, for instance, it wasn’t marketable, but I knew it was an original idea, so I kept it, and waited until the time was right.

Once I’ve ensured an idea is good, I begin my research, which takes about a year. I do this passively, while I’m working on other projects. At the end of the research process, I finesse my story and write down an outline. From there, I go to pages. I try to write ten pages every morning before breakfast. If everything is good, and my schedule is okay, I usually finish a book or a new work every three, four months or so.

Poda Poda: Finally, any last word for Poda-Poda Stories and your Sierra Leonean fanbase ( we boku! )

Namina: Fambul-dem, I’d just love to see you guys when I come back to Sierra Leone. If COVID gets better, I’ll definitely be at Ma Dengn this year. And if not, I’ll return to Sierra Leone at the earliest opportunity. Until then, stay safe, everyone.

Visit Namina Forna’s website at naminaforna.com.

Nadia Maddy's Journey: Charting Your Path as a Writer

We have another passenger on the Poda-Poda ! Poda-Poda stories chatted with Nadia Maddy, an author, a public speaker and the founder of Indie Book Show Africa. The author shared her writing journey, and tips on how Sierra Leonean writers can pave their own way in the complex world of publishing. Enjoy the ride.

Thank you Nadia for hopping on the Poda-Poda! Please tell us about yourself: Your background, your work as a lecturer and a writer, etc.

I currently live in London and teach Health and Social Care and Professional Development on the Bath Spa University programme. I am an ex pupil from International School and St Joseph’s Convent.

I started my creative experience with the BBC on the 90s TV Series, Video Nation with a video recorder and some ideas, then I decided with a friend to create and produce the Channel 4 documentary, Aliens Amongst Us, which won final selection at the Black Hollywood Film Festival in 2003. I wrote a couple of plays that were performed at The Half Moon Theatre, London.

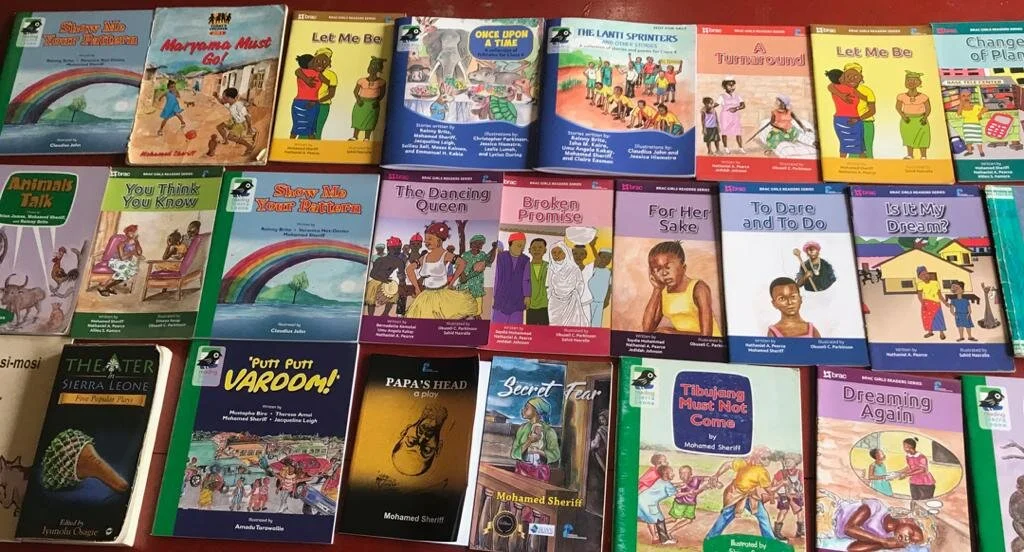

My first novel, The Palm Oil Stain– a story about one woman’s survival during the civil war took me 3 years to complete not long after I travelled to Sierra Leone to my father Yulisa Amadu Maddy’s funeral in 2014 and noticed that unless you’re a politician you are not commemorated. If you are , it’s in the form of a statue that no one is made aware of. I decided to start The Indie Book Show Africa Creative Writing Competition with PEN Sierra Leone for 11-18-year-old students in conjunction with PEN Sierra Leone. The competition was set up in honour of my father, director, playwright and author, Yulisa Amadu Maddy. I also run The Indie Book Show Africa - which comprises of African Literature recommendations on Youtube and acts as a resource for Writers interested in the African perspective.

When did you discover your love for writing and how did you decide to pursue it? Was it an easy journey?

I didn’t really discover a love for writing. Some people discover a love for it later on but that wasn’t me. It was always in me. Always. I was always writing poetry and stories as a child. I didn’t grow up with my father until I was 15 yrs old. Before that he would visit and I would spend random weekends with him. As a child I remember him being an African political activist more than an artist so I didn’t get to witness any form of art around him. So my writing as a child was from a place from within. When I did live with him for 2 years in Leeds, W Yorkshire, I was part of his drama production and toured the UK with Gbakanda Tiata. At the time, I wanted to be an actress but this was not an option for me as I was expected to go to university, so I turned to TV production and then writing. I wrote a lot of poetry during that time but the novel writing came much later. I decided to write ‘The Palm Oil Stain’ after going to Sierra Leone in 2006 and 2009. I saw how women were affected and yet everyone was talking about child soldiers. So I decided to write about what I saw after discussions with women who remained invisible during my visits.

Tell us a bit about your writing process? How did you work on the Palm Oil Stain (writing to editing) .

I just wrote it. I thought about it for 18 months. I had the story in my head from beginning to end. I developed everything in my head. Then I started writing it. I didn’t have any plan or plot written down. I wrote everything down by hand and then transferred it to my lap top. Then I saw the mistakes and gaps that needed to be corrected. After that I sent it out to beta readers (friends who were willing to read the first draft) who were people I knew would tell me the truth. That was the best part – receiving their feedback. I’m not afraid of criticism. I think the more criticism you get the quicker you can move forward with your work. Criticism is the best. Criticism makes you fly.

I did three rewrites before it was published and rushed it to an editor. I needed to get my book out before the Charles Taylor trial ended in The Hague, Netherlands. The book was published just before the verdict and I haven’t looked back.

How can Sierra Leoneans support you in carrying on your father's rich legacy in the arts? Especially young Sierra Leonean writers and creatives.

I work with PEN Sierra Leone to have the Creative Writing competition promoted in schools around the country. The first prize is £100, second £50 and third, £30. So far we have had more than 6 winners and I welcome all young people between the ages of 11-19 yrs old to take part. They can contact PEN Sierra Leone, Campbell Street. Contact Allieu Kamara or Nathaniel Pierce or directly indiebookshowafrica@gmail.com

What advice can you give to young Sierra Leonean writers who want to publish their work internationally?

I have met a lot of young Africans who are writing and publishing without waiting for approval from the big boys. Those days are over. There are a lot of publishing houses all over Africa as well as UK, Europe, America and Canada. Africans should be thinking about publishing in places like India, China …possibly even South America.

Publishing in Africa is a thing too. Now, you can upload your book to the Nigerian publishing house - Okadabooks.com and start selling your book straight away - make some money. Things have changed dramatically. We have a publishing company in Sierra Leone run by Mallam O, The SLWS Series - https://sl-writers-series.org/index.php/en/ They also help and support young writers. I understand that it is a lot to take in and there is in fact so much opportunity it can be overwhelming. But I think we need to realise that we can publish around Africa as well as internationally. The mind-set has to change, once your book is written it has become a product that you are going to sell, so you have to think about the different distribution points that you want to sell your book to.

One of the main concerns that I have is editing. Young people are not aware that they need to get their work edited and that can be expensive. It’s an African problem and one that writers and publishers are trying to tackle. If you can get your teacher or a member of your family to edit your work it’s a good start but if you want to publish internationally – then your work has to be seen by a manuscript developer, a copy editor and a proof reader before you can think about having a chance at being accepted. We all know that we don’t have those resources. So this is a problem.

That’s why SLWS series and PEN Sierra Leone may be good places to get the resources and experience that can help you attain the next level.

Stepping Out of the Cocoon: Sierra Leonean Literary Production

Poda-Poda Stories interviewed Professor Miriam Conteh-Morgan, Acting University Librarian at the University of Sierra Leone, to shed light on how Sierra Leonean literature has been archived, and accessed, especially in a world where technology and digitization has become very important.

Thank you for granting Poda-Poda Stories this interview. Please tell us a little bit about yourself: your academic background and your current work.

I am Miriam Conteh-Morgan, currently Acting University Librarian at the University of Sierra Leone. In that position, I coordinate the professional activities of the libraries of the three constituent colleges that make up the University. Each college library has its own head, and I head the one at IPAM. I came into librarianship 21 years ago after 18 years pursuing my first career.

After graduation with a BA (Div II) from Fourah Bay College in 1981, I taught English and history at the secondary school level, first at my alma mater, St. Joseph’s Secondary School and then at Albert Academy. During this period, I took two study leaves, first to do a Diploma in Education at FBC (1984) and then a master’s in Linguistics and English Language Teaching at Leeds University in the UK (1987). In 1989, I joined the Linguistics Department at FBC and left three years later for the United States, in 1992. There, I continued teaching English (mostly writing courses) and African Literature at various universities in Ohio and also English at Harvard University during the summers of 1996, 1997 and 1998. However, after so many years of teaching, I was ready for new challenges, though I preferred to stay in academia. So that’s why I chose librarianship, and completed a Master of Library (and Information) Science degree in 1999, with a specialisation in academic librarianship.

In December 1999, I was hired by The Ohio State University (OSU), the institution where I had been teaching African Literature, as a reference librarian. That proved to be a very stimulating and academically rich experience – it is a top tier research institution – and there I grew intellectually and professionally, published articles and books and was promoted Associate Professor in 2005. For personal reasons, I resigned to return home in November 2013, back to University of Sierra Leone, but this time in a different capacity at another constituent college, as head of the IPAM Library. I like to quip that the hills and valleys of Sierra Leone echoed their cry in my heart!

What an impressive journey, and well done for coming back home. What do you currently do at the University of Sierra Leone?

I love my job at the University of Sierra Leone! In the 6-plus years I’ve been here, my main focus has been to enhance the teaching, research and learning experiences of our faculty and students by a) modernising the library collections through the acquisition of recent research print and electronic resources, b) enriching the delivery of library services using information and communication technologies and c) creating electronic pathways through which research from Sierra Leone flows much easier into the global space.

And I wear other hats. I am also the Assistant to the Deputy Vice-Chancellor of IPAM (deputy head of campus, that is); I serve as chair or member of numerous campus and university decision-making bodies and committees, supervise dissertations, and when time permits, I teach a course in either Communication Skills or Information and Knowledge Management.

From your experience in academia and research, do you think accessing Sierra Leonean literature has become easier recently, and what are some of these channels been used?

Let me start off at the continental level. African literature has exploded in terms of its creative energy and global reach in the last 20 years, I would say, and this is mainly due to factors among which are greater writer mobility, more publishing options and the accompanying higher visibility, and the teaching of African works in World Literature courses in the US and Europe. In other words, more African writers live, work and travel more widely within and outside Africa; there are now multiple pathways for publishing outside of the gatekeeping multinational outfits of previous decades (think Heineman’s African Writer Series or Longmans) – self-publishing, online outlets, co-publishing agreements between African and international publishers etc; and what some critics think is a “whitening” or “lightening” of themes and genres that pander to non-African sensibilities. All of these have made writing from Africa more global and easier to access, and consequently studied increasingly in universities around the world.

So having said all this, the question now is seeing how Sierra Leonean literature fits into that nexus. We would need to first take a closer look at its production. The traditional route of print publication is still patchy in Sierra Leone. There are really no real publishers to speak of except, perhaps, for Sierra Leonean Writers Series, for which its founder, Professor Osman Sankoh deserves high praise. With its mission “[t]o identify, encourage and support writers of Sierra Leonean origin and to publish and disseminate their works in Sierra Leone and in the world at large” (https://www.sl-writers-series.org/index.php/en/about-slws, accessed April 24, 2020), SLWS has single-handedly changed the direction of Sierra Leonean creative writing with publications in all literary genres, though poetry and novels dominate their list. Acclaimed and prolific writers such as Syl Cheyney-Coker and Lucilda Hunter have appeared under this imprint, as well as emerging ones; others have launched their writing careers there, having gone on to publish multiple titles with SLWS. There are other publishing houses that also put out titles (Gbanabom Hallowell, for example, who has been an SLWS author has also published his later collections under the SierrArts imprint) but I am not very sure about their staying power. Time will tell.

The next issue to examine is the writing itself. Are there enough writers in Sierra Leone? I really cannot answer that question but I can hazard a guess that not many who have the talent or who need to hone their skills are getting discovered and nurtured. This leads to more questions: what can we do to encourage more creative writing? On whom does the burden lie? Again, I don’t know, but I can offer a thought or two.

Maybe targeted publishing could be a propellant for emerging Sierra Leonean writers. By targeted here, I mean catering to a specific group of writers by creating a safer zone into which they can step and grow. I’m thinking of examples such as the feminist publishers in East Africa and South Africa, Femrite, and Modjaji respectively, which have done a phenomenal job of bringing more women’s voices into the African literary space. Edwidge-Renée Dro’s Abidjan Lit Collective has pulled together such books by Black women writers into what she calls a ‘feminist library’ so as ‘unearth’ their stories.

We may also need to look beyond the book publisher to create a wider space for showcasing literary works in Sierra Leone. Literary magazines are another avenue. It is common knowledge that many award-winning writers around the world first published their short stories, excerpts of full-length works and poems in literary magazines. As far as I know, none exists in the country. So what are we waiting for?

For now, a couple of major roadblocks to accessing Sierra Leonean literature in print in the country are the mere physical unavailability of books there, and the low return on investment for both writer and publisher. Writers put their time and energy into creating the works and publishers finance their production; however, there is hardly a bookstore in the country where the books can be sold and bought. And even if there were, reading has become such a dying pastime that I wonder how many people will want to buy a book for leisure reading, assuming, of course, that the book is even affordable. There’s much work to be done here. And as we know of course, book piracy remains the bane of writers and publishers. Respect for copyright is a problem in Sierra Leone, as evidenced by the multiplicity of pirated books on sale in street-side book stalls.

Luckily, there are other options that writers can pursue that may be worth their while. And that is, harnessing the power and reach of new technologies. Indeed a few, especially budding poets, are taking advantage of them to reach online audiences via social media. For example, there is Samuella Conteh who shares her beautiful, evocative poetry on Facebook (I don’t know whether she has a collection in print) and a young lady going by the Twitter handle @the WriterAdeola who tweets about her poetry performances. So even if some of these new writers may not have yet marked their voices in print, which would meet a very limited national audience anyway, they certainly have a bigger advantage in using electronic platforms, bearing in mind, on the other hand, of course that social media is itself limited to one’s own circle of friends or followers. Nevertheless, it could be more helpful than waiting for one’s work to appear in print, if ever.

The one digital medium that I don’t see being exploited much by Sierra Leonean writers, though, is podcasts. When in 2006 I started researching authors for the electronic research database I was developing at The Ohio State University, The Literary Map of Africa (https://library.osu.edu/literary-map-of-africa), I was amazed by the number of podcasts of radio and television interviews and readings by authors that I found. So I think this is one avenue that could help with discoverability and accessibility.

Also, I am not sure if the full potential of YouTube is being actively explored. There may be a few creatives with their own channels, or at least who are part of other groups’ channels. Vicky the Poet on the UNFPA SL channel comes to mind. This is an international organisation showcasing her, and they might have other platforms where her work lives. If so, that’s great. But use of global platforms over which one does not have total control could be of short-lived advantage. I mean, the platform could change from free to paid, for example, and many of our writers may come to lose their content if they cannot subscribe. Or worse still, the site could be taken down before one realises it – the impermanence of online resources is not a secret. And sometimes, the rules of engagement of hosting platforms stifle creativity; here I am thinking about, say, their rules on the use of profanity, even if the writer believes s/he is covered by poetic licence.

Another option not yet seen at all, let alone exploited, in Sierra Leone is the audiobook. I met a young lady at a conference in Ghana last year (2019) who had started that country’s first audio book digital platform a few years ago, whose reach is now worldwide. I follow Akoo Books (http://www.akoobooks.com/) keenly because I think that while the concept of audiobooks is pretty novel, they are simply modernising the ancient mode of storytelling, so it would be interesting to see how it evolves.

Do you think digital is the future for archiving Sierra Leonean stories, or do we have a long way to go for that to happen?

The exploitation of digital options in a country that has a dearth of book publishers can well be the lifeline Sierra Leonean literature needs. These could be online magazines, digital repositories and multimedia platforms where creative writings and related productions (podcasts, videos, music, art etc) could be archived. I definitely can see a revitalisation of and boost for our oral literary culture in the latter – - archived live storytelling performances, can you imagine?

These outlets, however, need to be home grown, I would argue. Local ownership is very important for some of the reasons I mentioned earlier. But first, there needs to be visionary Sierra Leoneans with the deep desire to believe in and start up such ventures, like Professor Sankoh did for print publishing. With regards to digital magazines, there are examples on the continent that can serve as models for us here: Jalada (https://jaladaafrica.org/), Kwani (http://kwani.org), Saraba (http://sarabamag.com) and Afridiaspora (https://www.afridiaspora.com/ ). So how about throwing a challenge to Poda-Poda?

With wider internet penetration in the country, cloud computing, coupled with a growing tech-savvy youth population, I foresee digital literature growing as well. That would certainly bend the arc of our literary culture. But whether or not Sierra Leoneans are ready for e-reading is another matter altogether. We’ll see if “build it and they will come” will work.

But while waiting, writers should step out of the cocoon to explore what’s happening in other African countries and submit their works there for publication. Perhaps they themselves are the future of Sierra Leonean literary production that we all have been waiting for.