Ishmael Beah is a Sierra Leonean novelist and human rights activist. His memoir, A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, details his journey from a child soldier during Sierra Leone’s brutal civil war, to a new life in the United States. He has gone on to publish two more books, Radiance of Tomorrow, and Little Family. Beah’s stories always bring into focus the realities of people considered to be on the margins and give readers a deeper understanding of the complexities of everyday lives. In this conversation with Poda-Poda Stories (via skype), he shares why it is important to write such stories, and why we need more Sierra Leonean storytellers on the global literary scene.

Poda-Poda: Thank you Ishmael Beah for being a part of this. If you could just start by telling us a little bit about yourself and your background.

IB: I am Ishmael Beah. I am a Sierra Leonean. I am a New York Times and international Bestselling Author. I’ve written three books to date. The first one was out in 2007, called A Long Way Gone; Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, that recounted my experiences of the war in Sierra Leone. I then continued with a novel called Radiance of Tomorrow that looked at how people return to places that have been devastated by war. And the latest book is also novel called Little Family, that is set in an unnamed African country, but Sierra Leone is the main inspiration behind it, and it came out at the end of April this year (2020) in the midst of all this crisis. I am also a UNICEF Goodwill ambassador, specifically for children affected by war globally. Lastly and most importantly, I am a husband and father of three wonderful children, which of everything that I have achieved, my remarkable family is the one thing that I am the proudest of.

Poda-Poda: Amazing! Tell us about your new book, Little Family. Why did you decide to write this story?

IB: Little Family is about five young people, who have decided to ostracize themselves from society, and live at the margins, to seek freedom, and define what that means to them, in their own way. Over the years, I have lived in Mauritania, Nigeria, Senegal and back home again in Sierra Leone, and I was observing how young people are struggling to define themselves.

There are local traditions, systems and values that have collapsed, but then there’s also an importation of new values and ideas from foreigners coming in. So young people find themselves in between, trying to decide what they want to embrace. Do they want to be more traditional or do they want to be more modern, and what that reality means? So, it was really about trying to answer that question that I then created Little Family. I wanted to see whether this is possible, and if it’s not, what is the burden of history? What is the burden of the place you live in and how do you unshackle yourself from it, and be free in your own way?

Poda-Poda: In this book you’re talking about a group of homeless children. They are the heroes of this story. You really illustrate the humanity of people we often consider to be on the margins of society. These are young people we see and encounter every day, but we don’t really have a window into their lives, and in this book, they have created a space for themselves. I was wondering whether this was a metaphor for building a new future for ourselves, especially as young people in Sierra Leone?

IB: Absolutely! This was a metaphor, but this was also based on certain observations of reality. I think whenever you decide to ostracize yourself from society, or you don’t like what’s going on, you build your own little family. You build your own group of people who are like-minded, who think the same way, because if you express your feelings and your thoughts to other people who don’t understand, you feel judgement. As human beings, this is how we are. When we live in an environment without a supportive mechanism, we recreate a space that allows that for us. I also wanted to show that people who are at the margins of society are intelligent, but we don’t often think of them that way.

For example, if you encounter a guy who’s selling tissue paper on the street. Every morning, this guy goes to the big store to buy tissue paper, so he can sell it to you and for your convenience of not leaving your car and going to the store. So, this guy is an economist, he understands the market space. But we do not give credit to the intelligence of what it means to survive. When you are surviving, you are an astute observer of a society that’s thriving, because you see the cracks in it, and it’s through those cracks that you survive. So, you’re more aware of it, than the person who is supposedly better off than you.

I wanted to show that intelligence is also not based on education. Education is just so that you can join the workforce. Intelligence is something that you actually have. So, I wanted to show that there’s brilliance on this continent. Every child that you meet that is fifteen, or sixteen years old, already has a PhD in economics, psychology, and sociology, just to survive daily. I wanted to celebrate that.

Poda-Poda: It’s good to highlight that people on the margins are very intelligent and street smart. It’s also good to show the darker sides as well. You’ve highlighted sexual assault and gender-based violence in your past books, and recently Sierra Leone has been rocked by news of rape and gender-based violence cases. I was wondering what your take was on that, because the people in Little Family are also at the receiving end of the darker sides of our society which include rape and sexual violence, but it’s not always that their stories are brought to the fore. What is your commentary on that?

IB: It’s been very difficult for me to think about this, because I am aware that Sierra Leone has had cases of rampant sexual assault, particularly towards very young girls. The last time I was in Sierra Leone, I was out in Makeni, and there were so many cases where even teachers were abusing their students in schools. Through UNICEF I was dealing with a lot of these cases. I also have two girls, one is six and the other is four, and I think of them when I hear these stories. In my work, I’ve tried to show how, in Sierra Leone , there has been a behaviour that has been accepted, especially from the male point of view, to sexualize and disrespect women and girls, even when they are as young as three years old. For example, you’ll go to parties and the music is playing, and someone will say “ ay bo, call da pikin leh e kam shake am for we” . This is where it begins. What we don’t realise is that we are doing certain things that are leading to this. While we need to educate young boys to respect young women, there are even older women who also perpetuate these attitudes and beliefs. I have witnessed a grandmother, a mother or an aunt tell a girl “tell da you man de leh e sen for me ya”. So there are so many things that we need to work on. And it really needs to come from respecting women, understanding that women are not products to be married off, or to have as girlfriends, but that also they are intelligent members of society that contribute to it. They’ve done it in history, and they will continue to do so.

When I write, for example in Little Family, the main character is Khoudiemata, who decided that she is going to be as free as possible, that nobody is going to make her what she doesn’t want to become. So, it’s also good for young women and men to read literature and see stories of women that are not highlighted enough. This( sexual violence) is a very serious issue that needs to be taken up by the entire country, and we need to be honest about what’s going on.

Poda-Poda: And that’s also the power of literature, it gives us the chance to be open and honest about things that are often considered a taboo. Going back to the theme of storytelling and narratives, in your books you’ve highlighted not just your own experiences, but the experiences of many young people in Sierra Leone. In our attempt to share those stories with a wider audience, how do we stay true to our experiences?

IB: Well I started writing particularly out of that frustration. I started writing because there were a lot of people writing about Sierra Leone that were not Sierra Leoneans. They visited for maybe one or two weeks and then wrote books about Sierra Leone, that didn’t quite paint the full picture. People come to our country and then all of a sudden are seen as the ‘experts’ of our lives, and they shape the way the world conceives who we are. So, my writing really came out of that frustration.

My writing has been to undo some of those things and put the narrative in our hands. We should tell our own stories, our incapabilities and shortcomings. We should be in charge of telling those stories, because when we tell our own stories, we give ourselves agency, we show how multifaceted we are. This is very important, because it not only shapes how people view us, but also how we think of ourselves. So, I’ve been a big champion of that. In all the books that I’ve written, none of them are set in the US, all of them are set in Sierra Leone and similar countries. And this is very deliberate. Not that I don’t have stories to tell about the US, but there are other books that tell those stories.

I want Sierra Leone to have a stronghold in literature. I want other young people to see that’s possible to put that intelligence on paper and keep record of our experiences. When you write, you always have to write about things that are bigger than yourself. And I think that is why my work has been so successful, because when people read it, they know I’m writing about something that’s bigger than me. And for young writers in Sierra Leone, this is what I would say to them: Don’t write because you want to be this “superstar” on your own. Write because you want to see the beauty and complexities of the society we live in, and how people can see themselves in literature. For example, when I write, I use our names for my characters: Khoudiemata, Mohamed, Salamatu, these are names that are not usually in literature, and I want them to be in literature. And when a girl named Salamatu reads a novel, she’ll say “oh, there’s someone like me”.

Poda-Poda: There have been protests in the United States that have reverberated around the world. The Black Lives Matter protests is fast becoming a global movement. As a black writer living in the US, do you feel a sense of duty to tell the stories of the different layers of blackness, and make those different connections?

IB: Absolutely. Racism is not just an American thing, it’s a global thing. People dislike you because of how you look, because of your blackness. And when it comes to that, it does not matter whether you’re from Sierra Leone, or wherever else. One of the earliest police shootings of black people in New York, was Amadou Diallo, who was from Guinea. And when the police shot him, nobody asked where he was from. He was black, and that is the first thing they saw. So, this idea of blackness is a global thing. Because of how black people have been portrayed through time, through the Point of View ( POV) of white people, we are not portrayed as people who have intelligence, as people who can succeed .

For me as a writer, there’s a burden and a desire to undo that and to show people the multiple experiences of blackness. Going back to my work, my stories usually don’t have any white people in it and if they do, they are not shown as “white saviours” because we save ourselves. So, I want to show that we can exists without the POV of white people. We don’t need them to live or imagine, we’ve always lived and imagined as people.

Poda-Poda: Speaking of blackness and visibility, and looking inwards, how can we make those connections as Sierra Leonean creatives at home and in the diaspora, while decentring the white gaze and focusing on ourselves?

IB: That is what I’ve been doing over the years. Every time I put something out, I try to collaborate with other black writers, so that we can have more of us telling more of our stories. Clearly, I am one person, so my work will always be from my own point of view. So, I’ve been trying to encourage young writers back home to also put their work out there.

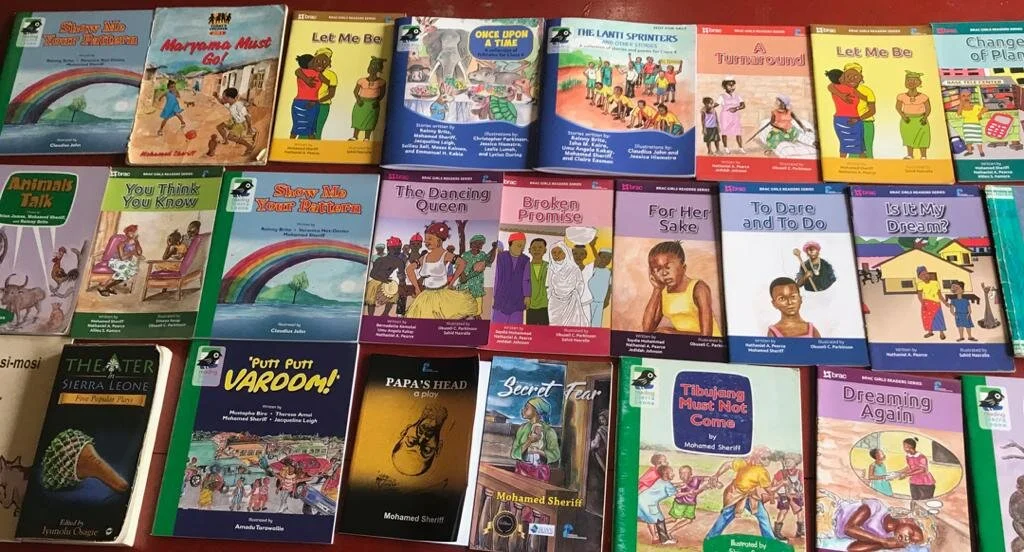

One of the things that I did in my new book is that I wanted the characters to have a visual representation. I asked my publisher to look for an African black woman creator (illustration and drawing) to draw the characters in Little Family. And luckily, they found Ngadi Smart, a Sierra Leonean illustrator. And she drew these amazing photos of the characters. So now the publishers know that there is this Sierra Leonean illustrator who we can hire for my next projects. For me, each time I do a project, I throw a hook out there to bring somebody to the forefront. And it’s very important to do that so that people can see the breadth of our intelligence on the continent.

Poda-Poda: We definitely need more of us telling out stories. What advice would you give to aspiring writers from Sierra Leone?

IB: Read a lot! Read a lot of what other people are writing. If you can, find a mentor and a circle of people who can review your work for you. Write your own truth, write your own stories. Don’t let anybody tell you that you cannot do it. Because I also know that we come from a culture where, there’s very little encouragement in the creative space. People will try to push you down or say that you are not good enough. When I first expressed that I wanted to write, I had some of my friends in Sierra Leone who tried to discourage me. But I thought to myself “why not?”. So, find people who are going to encourage you for your craft and not people who are going to push you down. You have to surround yourself with people who can empower you. Your platform (Poda-Poda) is a remarkable one, and there are people creating these sorts of mediums, for people to showcase their work. So, write, read, and find spaces that will support you.

Poda-Poda: A question I always ask writers is, how has writing saved your life?

IB: It saved my life in many ways. How I started writing was that I came to the US in 1998, and I was adopted into a white Jewish family. And I had left the war in Sierra Leone, and I had nothing. All I had was my Sierra Leone passport. And it was very difficult to get into school, because I didn’t have a report card or any school records. And even though I could stand in front of people and speak English to them very well, it wasn’t sufficient for them, because they still needed proof that I had been in school before. So, I started writing to show that parts of me had existed before people met me in the US. And I remember my first essay was titled “Why I do not have a report card”, because most people kept asking me. This essay was a window for me to explain that when you’re running for your life, you don’t’ think of your report card !

So, writing for was a way to show who I was before people in the US met me, and to correct whatever perception they had of other people from my country. Writing has saved my life by allowing me to show people that I am as human, as intelligent, and as complicated as they are and that people from my country are not one-dimensional. For example, when we had Ebola, there were so many western journalists writing a lot of nonsense about Sierra Leone, I had to jump in, and I wrote an op-ed for the Washington Post. So, writing has always been a way to reassert our humanity in other people’s mindsets.

Poda-Poda: What is the one thing you miss about Sierra Leone?

IB: Oh, I miss everything. There’s something about Sierra Leone that you cannot find anywhere else, at least for me. Everybody is a natural comedian and natural storyteller, and every encounter is always interesting, especially for me as a writer. There’s so much passion in everything. Even in our difficulties, we have passion and humor. I miss that. I miss that people have discussions about the most meaningless things. I miss the food. I miss our mannerisms, how laidback people are. I miss speaking Krio. I miss speaking Mende. Our languages are constantly evolving and there’s so much musicality in them. I can go on and on. I miss everything.

Find our more about Ishmael Beah’s work on ishmaelbeah.com .

Questions and Interview by Ngozi Cole.